How Orwell’s time at the BBC inspired Nineteen Eighty-Four

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Turning up at Broadcasting House in 2017 for the unveiling of the BBC’s George Orwell statue, I came across Orwell’s son, Richard Blair, being interviewed by Amol Rajan and a posse of cameramen. “I told them about the girls’ school and the lunatic asylum,” Richard volunteered a few moments later, “but they didn’t seem very interested.”

As might have been predicted, the subsequent publicity-fest managed to ignore Orwell’s most memorable comment about the atmosphere of the BBC when he worked there in the early 1940s – that it was “something halfway between a girls’ school and a lunatic asylum, and all we are doing at present is useless or slightly worse than useless”.

Orwell would later describe the 27 months he spent in the Corporation’s employ, between the summer of 1941 and the autumn of 1943, as “two wasted years”. Yet this was a typical Orwell overstatement, part of the myth that he enjoyed creating around himself when he was alive, and which critics have been unpicking almost since the moment of his death.

If one part of Orwell was profoundly irritated by BBC bureaucracy, BBC nitpicking and BBC protocols, then another seems to have been stimulated by his job. Far from seeming ground-down and care-oppressed, the man who features in the famous group photo of Eastern Service broadcasters at the microphone – T S Eliot and William Empson are on hand – looks to be positively enjoying himself.

Orwell arrived at the BBC in September 1941, pleased to be there – his poor health denied him most other forms of warwork – and happy to be employed by its Eastern Service, which allowed him to broadcast to a part of the world with which he had ancestral ties. (He was born in Motihari, then in British India.) Variously described as “talks assistant” or “producer, Indian Section”, and at a salary of £640 per annum – his first regular money since his school-teaching days back in the early 1930s – his remit was to write and produce a series of commentaries on the news for transmission to India and the Far East, while commissioning other programmes on educational and cultural topics.

Some of this commissioning seems horribly mundane. One of the earliest letters dispatched by the incoming talks assistant was to a P H Chatterjee, asking whether he would broadcast about rural district councils in a series called How it Works. At the same time, the work was concentrated and laborious. Having previously got by as a literary freelance, constrained only by his deadlines, Orwell now found himself required to put in a five-and-a-half-day week. All this took a toll on his damaged respiratory system, and one of the features of his BBC days was the amount of sick leave he was forced to take. Six weeks into the job, he went down with a bad attack of bronchitis, and there were two more long periods of absence, in December 1941 and January to February 1942.

If Orwell was never well during his time at Broadcasting House and on the Corporation’s premises at 200 Oxford Street, he was also increasingly frustrated by many of the tasks he was obliged to perform. It wasn’t just that organising the talks schedule meant dealing with volatile and erratic contributors – Lady Grigg, wife of the joint under-secretary of state for war, was a prime suspect – but that from an early stage, Orwell began to suspect that his seed was falling on stony ground.

Audience-research techniques barely existed; there was no real way of knowing who in remote parts of the empire threatened by Japanese invasion was listening. Worse, with his reedy, monotone voice – irrevocably damaged by the fascist sniper’s bullet that had passed through his throat in Spain – Orwell was not a good broadcaster. Some primitive audience-approval ratings put him at 16 per cent, light-years distant from such titans of the airwaves as J B Priestley, and below even Lady Grigg.

Inevitably, Orwell being Orwell, this surface dissatisfaction was complicated by deep-rooted psychological conflict. His friend Tosco Fyvel recalled a conversation from early 1943 in which Orwell complained about the tedium of his job and the poor quality of the programmes. Surely he was exaggerating, Fyvel maintained. After all, he was working with interesting people, and there were war jobs far less agreeable than this? Nonsense, Orwell shot back. Agreeable warwork was the last thing he wanted, and as for the Indian Section’s output, even the cultural talks retained a propagandist element. Anything politically unsuitable was bound to be eased out.

All this sounds like the lament of a deeply disillusioned and unhappy man. To set against it are examples of Orwell the broadcasting innovator: his ability, for example, to convert stories by H G Wells and Ignazio Silone into half-hour dramas; his commissioning of his wife Eileen, who worked at the ministry of food, to devise a programme called In Your Kitchen, and above all Voice, a kind of literary magazine of the air that, as well as featuring Eliot and Orwell’s colleague Empson, had room for newcomers to the literary scene, such as the flamboyant Sinhalese poet M J Tambimuttu and the West Indian writer Una Marson. Poetry on radio may, as Orwell once put it, sound like “the muse in striped trousers”, but the surviving scripts would give many a modern books programme a run for its money.

And then there are those tantalising moments, in a succession of run-down Corporation offices, in which the germs of Nineteen Eighty-Four start to stir. There was a real Room 101 at 200 Oxford Street, a nondescript space used for sorting mail. Equally, the claustrophobic, rabbit-hutch ambience of the Ministry of Truth, where Winston Smith sits falsifying back-numbers of The Times, clearly has something to do with Orwell’s own experiences of office life.

The owlish, scholarly Empson probably gave something to Winston’s soon-to-be-liquidated colleague Syme, while the scene in which Winston and Julia, snug in their love nest above Mr Charrington’s antiques shop, listen to the prole woman bawling out a popular song may reflect what Orwell defined as one of the BBC’s most characteristic sights: an army of early-morning charwomen collecting their kit and marching off along the corridors, singing as they went.

The BBC, too, offers a series of glimpses of Orwell, as it were, in action: detached and self-engrossed, but innately purposeful. Here, in a world of wartime rationing and new varieties of foul-tasting fish, the canteen food was rated better than average: Orwell pronounced it marvellous. Finding out that the facilities ran to a special-effects department, he is supposed to have rung up and asked for “a good mixed lot”. Meanwhile, there were always opportunities to prosecute the class war. Taking a colleague named John Morris, whom he seems to have disliked, to a pub, he was appalled when the younger man requested a glass of beer. Morris had given himself away, Orwell sternly pronounced: a true member of the working classes would have asked for bitter.

Late in 1943 came the offer of a job on the staff of the Left-wing weekly, Tribune. Animal Farm was begun almost from the moment of Orwell’s departure. As for his possible view of the BBC’s current difficulties, Orwell seems to have had no objection to state broadcasting, or indeed to propaganda – he merely believed that both could be done better.

But one last mystery of his time there remains unsolved. Although no recording of his voice exists, the story goes that an acetate of a programme on which Orwell featured – possibly an edition of Voice – turned up in the Corporation’s Caversham archive some years back, but disappeared again before it could be properly investigated. It may very well still be there in the vault. For the record, Orwell is supposed to have sounded like Alan Rickman.

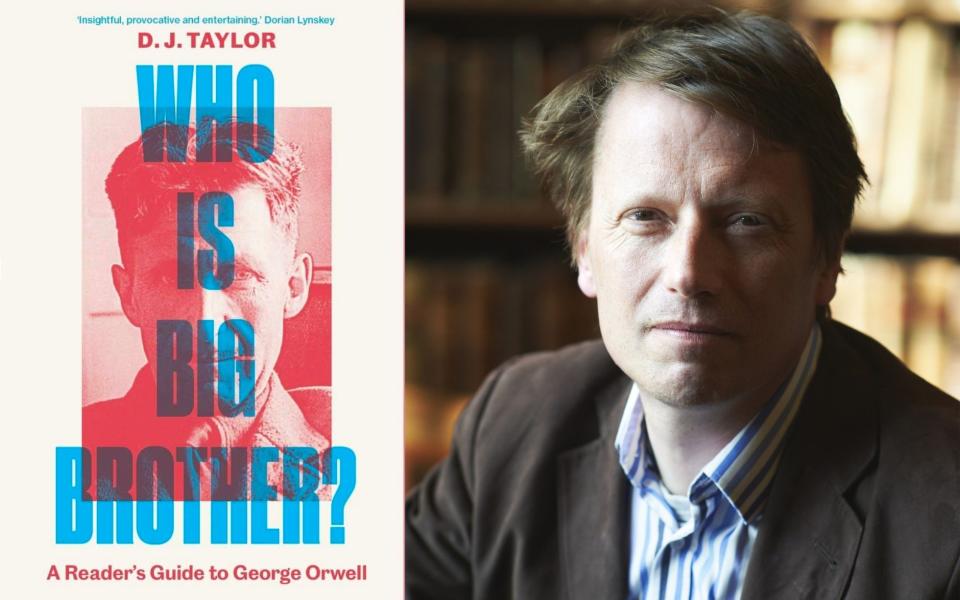

D J Taylor’s Who Is Big Brother? A Reader’s Guide to George Orwell is published by Yale on Tuesday