East Austin's Holly Power Plant murals are part of neighborhood's history. Will they last?

Editor's note: This story has been updated to show the correct title for Reynaldo Hernandez, the project manager for the Austin Parks and Recreation Department during the construction of the Holly Lakefront Trail.

A large chunk of wall is missing and the rest is covered with cream-colored paint, but Armando “Taner” Martinez can still trace out the shapes of what was once his mural: a Mexica pyramid, the Virgen de Guadalupe and two indigenous figures.

It’s one of many Holly Street Power Plant murals that could disappear if steps are not taken to save them. Three decades of weather and a lack of attention have worn the art on the plant’s original sound walls, threatening a set of physical structures that represent the neighborhood’s clash with the power plant, which closed in 2007.

In the past two years, additions to the lakeside trail system have opened formerly inaccessible parts of the plant to joggers, cyclists and families. Once industrial and now fashionable, East Austin has experienced rapid demographic change as the neighborhood’s housing prices rise. Long-standing residents like Martinez and Arte Texas Executive Director Bertha Rendon-Delgado want the city to commit to restoring the works. What isn’t improved, they said, won’t be valued.

“It needed some help … we wanted some help,” Martinez said of his mural. But when he saw it was painted over, “it hurt. I felt like they’d destroyed part of me.”

More: Revival of Holly Shores mural seen as 'a victory' for neighborhood

Who made the Holly Street Power Plant murals?

The walls were a victory of their time. In 1991, residents of the predominantly Mexican American neighborhood successfully lobbied Austin Energy to replace the exterior chain link fence with a sound wall. The plant’s machinery, horns, alarms and communication systems blared over the surrounding blocks.

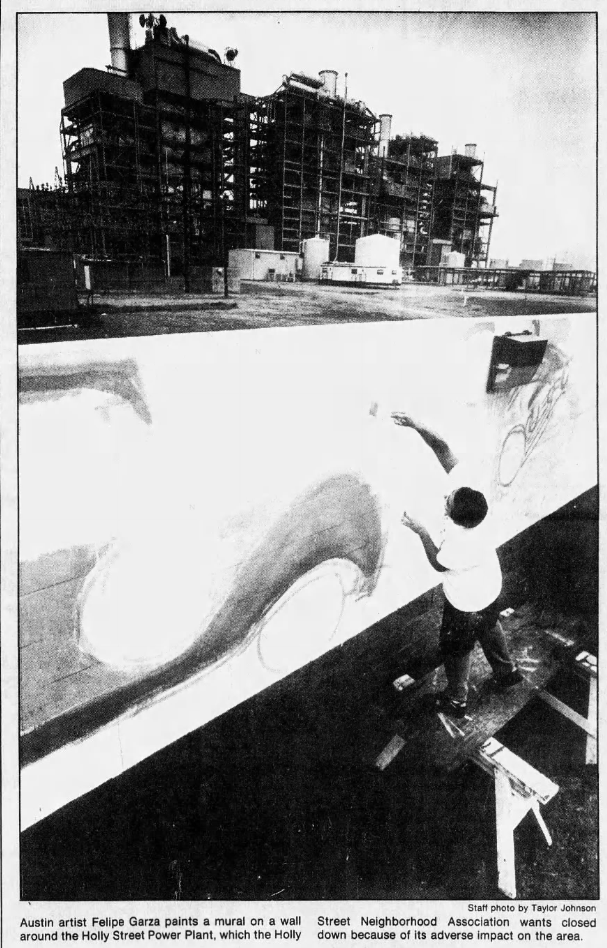

The city commissioned local artists — most Mexican American — to paint the walls in 1991. The list included professional artists such as Fidencio Duran and Arleen Polite and a young generation of South and East Austin graffiti artists such as Martinez, Oscar “Tez” Cortez, Robert “Kane” Herrera and Joe Perez. At the time, the project’s organizer, Felipe Garza, told the American-Statesman that the mural project was to be the largest in the state.

Murals eventually covered most of the west, north and east walls. The west and the north walls contained mostly commissioned pieces, and the east wall became an open canvas for local residents.

Martinez, who was 20 at the time, said Garza told him and the other young graffiti artists to promote public good in their work. He painted “Paz en el Barrio” and “Winners Do It Drug Free.” It was a novel idea for him at the time, but one he has fully embraced since.

Rendon-Delgado said the neighborhood graffiti artists of the 1980s and ’90s took inspiration from an earlier generation of East Austin Chicano artists such as Ramon Maldonado and Raul Valdez by politicizing their subject matter, in part with the indigenous imagery and use of Spanish. The power plant mural wall is the most concentrated example of this second generation’s work.

What has happened since?

With time, the art faded. The deterioration, according to a Preservation Austin history, was the result of a low budget, a lack of lasting art materials and the walls’ cinder block, “a cheap and porous material in which water was absorbed very readily, damaging the painted murals quite easily.” Graffiti tags appeared over many of the works.

One mural, Martinez’s “Paz en el Barrio,” was damaged when a wall was removed to create a large pathway to Metz Park after the plant closed. The rest of it and the adjacent eastern wall, which had uncommissioned community graffiti, were later painted over. Rendon-Delgado and Martinez said the city had promised to preserve “Paz en el Barrio” in community conversations surrounding decommission.

Meghan Wells, the city of Austin's cultural arts division manager, said it is unclear whether that mural belonged to the city’s Arts in Public Places program’s documented collection but that it “should not have been touched.”

Reynaldo Hernandez, the project manager for the Austin Parks and Recreation Department during the construction of the Holly Lakefront Trail, said that Austin Energy conducted the original removal of the “Paz en el Barrio” wall and that his department, which now owns these walls, removed and altered additional walls in 2022 and 2023.

Austin Energy spokesman Matthew Mitchell said that the utility provider’s records could not “confirm nor deny” its involvement in removing or altering walls.

“They do it when you’re asleep, you don’t know. And someone’s got to go and dig it out,” Rendon-Delgado said.

She and Martinez grew up in the neighborhood and still live nearby, but the Holly Shores neighborhood of today contrasts with that of 1991. Tiny bungalows have increasingly given way to a herd of McMansions. The once heavily Mexican American blocks are now substantially whiter and more affluent.

The walls, she hopes, will be a sign of the East Austin longtime residents' love and fear they’re losing.

Murals’ future is uncertain

In a 2013 public art action plan, the city recommended the seven site murals it identified be “deaccessioned,” meaning removed. It never acted on this recommendation, and Wells said that removal is no longer the city’s intention, though no newer guiding plan appears to exist.

Delgado said the city told the East Town Lake Neighborhood Association on several occasions, including decommissioning, that there would be money to refurbish the murals.

Money has yet to be earmarked for most of the murals, Wells said. However, the city commissioned Herrera to redo his Chicanista “For la Raza” graffiti mural at the end of Riverview Street in 2018. And this year, it funded Fidencio Duran’s restoration of his folk-surrealist “La Quinceañera.”

Restoration dollars for the more than 400 public art pieces in Austin are limited and constantly in demand, AIPP collections manager Sean Harrison said.

Wells said the city is committed to maintaining the power plant’s history and the art that the community wants to preserve.

“We definitely don’t want to erase what it looks like,” she said. “The Holly Power Plant was traumatic for many. These murals were a way for many residents to heal.”

But it’s unclear when the city would have the money to finance the existing mural’s improvements, she said. Other options, such as private partnerships, could help raise money.

Martinez and Rendon-Delgado said they are disappointed that the city has yet to act to restore most of the works. (“They have money for art,” Martinez said. “Just not our art.”) And they’re concerned that a gentrified Holly Shores might prefer new art projects to preservation.

Martinez has redone two of the murals with his own time and material but doesn’t believe this is sustainable. Funding would allow him and others to use lasting materials and set aside time for the projects.

Regardless of what money manifests, he said, he’ll find his own way to reclaim the walls. Staring at the cream-colored paint over his former mural, Martinez muttered a few possibilities of what he could paint next.

“I’ll do something at the end of the day,” he said.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: East Austin's Holly Power Plant murals continue to fade