Dope House: Buying a Family Home Opened a Door to Hell

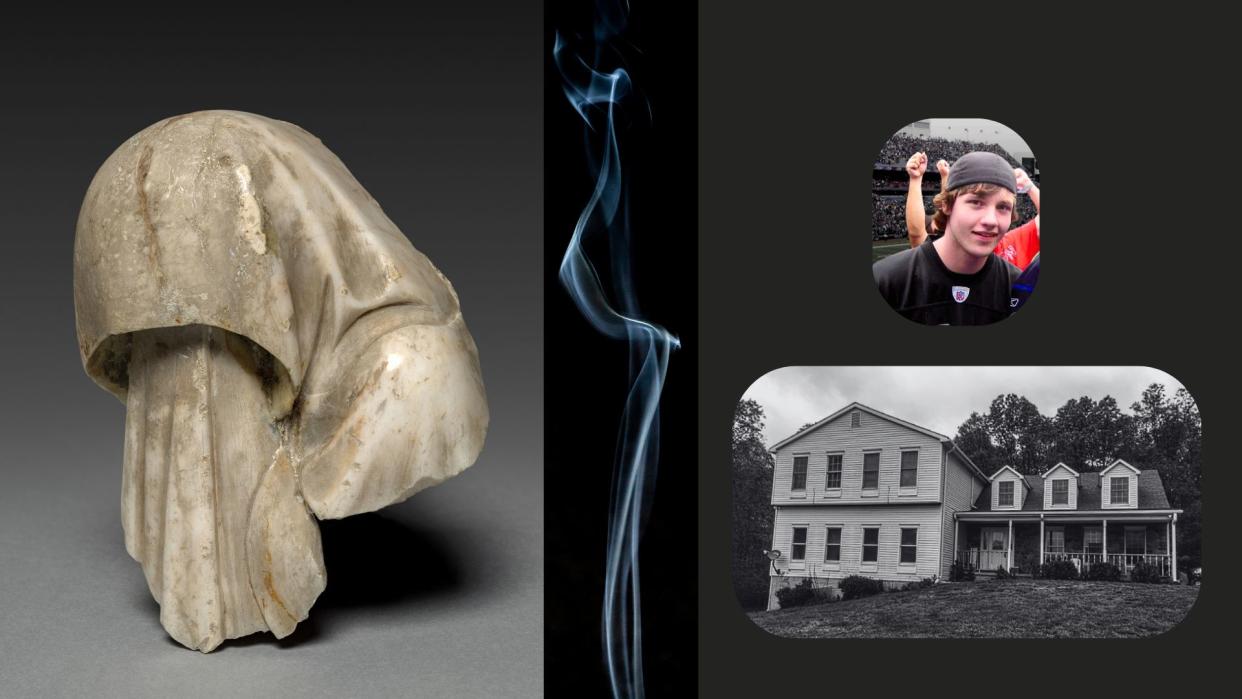

“Wow, they must really like four-wheelers here,” said Darren Griffith, as he drove his new blended-family up the drive of a phat manor for sale in rural Maryland.

“There’s like seven of them,” said Darren’s teenage son, Gunnar, counting the all-terrain vehicles lurking in the treeline of the property. “Can we keep them, Dad?”

More from Spin:

Foo Fighters, Noah Kahan Lead Bill For Renamed Connecticut Festival

Marcus King on Exploring Mental Health With New Album Mood Swings

Darren, 46, felt that the 6,000 square-foot house they were about to inspect, nestled as it is on 4.5 acres of gently rolling hills, would make a great home for him and Gunnar, along with Darren’s fiance, Michelle, and her two teens, Maia and Sidni.

The house on Sly Fox Lane needed cosmetic repairs, the listing said, and was being sold as is, which to Darren meant seeing past a few blemishes to its good bones and thereby score a great deal.

After looking at the wildly overgrown lawn and finding the front door conveniently, if unexpectedly, wide open, Darren, Michelle, Gunnar, 16, and Maia, 13, stepped inside (unable to come that day was Sidni, 15). Off to the side of the foyer was a stash of ATV parts (“Dad!), and ahead beckoned the main staircase.

“We walked upstairs and into a room and all of a sudden there’s a big hole in the ceiling,” says Darren. “And all the doors have padlocks. My fiance is kind of skittish, and she’s like, ‘I’m out. I’m out. We’re going. I don’t want to buy the place,’” laughs Darren. “So I’m telling her she’s gotta look at the house and how great it is.” Pressing on, they find a color scheme akin to the Church of Satan. “The bedrooms are all black—painted so black you can’t see.”

Back on the first floor, the family discovered whimsical alterations which perhaps prompted the realtor to suggest cosmetic repairs in the listing. “Bullet holes in the wall,” says Darren. “And smashed doors—smashed with people’s heads, it looked like. Like they pushed people’s heads through the doors. It was a shit-show here.”

The basement also displayed an idiosyncratic flair for home mods. “There was a bottom door in the basement,” Darren tells me.

“Bottom door?” I ask, confused.

“Yeah—down on the bottom of the basement, on the floor of the basement, there’s a door. Over the stone where they drilled out part of it,” he says. “To stick money in.”

Darren and Michelle take the plunge and buy their patch of paradise, delightfully situated as it is between the quaint town of Keedysville (established 1768; pop: 1,200) and the sommelier’s paradise of Big Cork Vineyards (mon dieu, the Malbec!).

“We saw the potential in it because the house is built very strong,” Darren says. “The walls are very thick.”

Moving ahead with the purchase, Darren organized a walk-through with a fire inspector and a building inspector. “They’re inspecting everything to make sure that there’s no leaks and that what we pay for the house is good,” he says.

After looking through the dark upper chambers, the group worked its way down to the first floor, where Darren opened a bedroom door. “There’s a naked Asian lady laying in bed,” he says. “She rolls over and her boob pops out.” The inspectors were startled, but the surprise naturist was blasé. “She’s all heroin-ed out, and is like, ‘Yeah, man, they told us you were gonna come, so whatever – that’s fine.’”

Moving on from electric ladyland they entered a room with a discreet hatch built into the ceiling. Opening it revealed two bricks of marijuana. Before Darren could react one way or the other, however, his building inspector piped up, saying: “Oh, you can’t touch that; it’s not your house yet.”

As the would-be proud new homeowners learned, the residence, owned by an absentee title-holder, had until very recently housed about thirty-plus squatters most if not all of whom apparently centered their squalid existences on drugs. And it proved hard for some to cut ties with their trap house extraordinaire.

As the day approached for Darren and Michelle to take possession, “they stole the back deck. It was a really nice little back deck—probably 10 foot by 20 foot—they took it off and burned it. They stole the shutters off the house. They pushed the rail going up the stairs until it was laying over, and then they stole our washer and dryer that were supposed to convey with the house!”

Nevertheless, Darren kept encouraging Michelle to see beyond the bullet holes, skull-smash damage, ceiling stashes, the fleet of stolen vehicles, the drug-money hidey-hole drilled into the floor, the nude junky, blacked-out drug dens, and the ongoing theft and arson.

Soon this dream home was theirs!

Shortly after moving in, and on a day Michelle, 45, was home with only her two daughters, the visits begin.

“I’m standing on the front porch,” says Michelle, “and these two guys pull up in a Corvette. One guy gets out and he’s wired to the car.”

“He’s what?” I ask.

“He’s wired to the car,” Michelle says.

“He’s … he’s what? He’s wired?”

“Wired to the car. With wires. He can’t move away from the car because he’s wired to it for some reason.”

“Oh.”

“He says: ‘Do you have my mail? We used to live here,’” Michelle tells me. “So I tell him that I do have some things, and I hand him mail—scared to death, because he is a big guy. They are two big gentlemen. Then he goes: ‘Would it be all right if you collect our mail for us? We’ll be back.” Scared, and painfully aware Darren was away, Michelle says she will.

A few days later, again with Darren absent, one of Michelle’s girls had a friend over. When the friend’s father came to pick her up, as he and Michelle chatted they spotted an SUV traversing the drive.

“I’m going to tell you something really fast,” Michelle said to the dad, who was a correctional officer. “I’m really sorry but this house used to be a drug house and I’m pretty sure this is drug dealers coming. I’m really scared.”

The dad assured Michelle he’d stay through this, and he set himself to deal with the unfolding situation. Out of the SUV, however, climbed a U.S. Marshal (“who looked like the Rock,” says Michelle). As it happened, he and the correctional officer dad knew each other.

“Ma’am,” said the Marshal. “We’re looking for some people who used to live here.” He pulled out photos of the gentlemen who had stopped by for their mail.

“Are we in danger now?” asked Michelle.

“No ma’am.” The Marshal said that her residence had been a convenient layover for the Corvetteers on their drug runs up and down the New York-Florida corridor, but word had spread that the house had changed status. “So don’t worry about it. You’re safe.”

Visitations, nevertheless, continued. Weekly.

With men arriving directly from jails and prisons, Michelle got a 175 lb Great Dane for protection. Some of those turning up expected to move back in and others wanted their mail. One postal-hopeful emerged from a van with his gut pouring out of a burgundy velour sweat suit. People came to sell drugs. Buy drugs. Beg for drugs.

Some came for pets, as Darren explains. “These two guys knocked on the door, and said, ‘Have you seen our Shih Tzu? We left it here.’ I asked why they had a Shih Tzu—wouldn’t they have been better off having a pit bull or a Rottweiler. ‘You’re profiling me,’ one of them said.”

Darren told them they did leave something here: “A naked Asian lady in the basement. And they go, ‘Oh, that’s Tia.’”

One day a group of four appeared. “They look like a couple Amish kids coming up with no hair on their lip—just a beard—and they had two girls. They were like, yeah, ‘Uh, where’s J.T. at?’ And I’m like, ‘JT doesn’t live here anymore.’ So he goes, ‘Well, he told us to come here.’”

Darren stops laughing for a moment. “These girls that they were going to trade for sex were all heroined out,” he says. “They were probably like 15, 16 years old, and drugged out. They had blank faces. And that’s why the padlocks were on the doors.”

“Not just to prevent theft?” I ask.

“For theft, but also when drugs were traded for sex. It’s very sad.”

These unsettling, aggravating, disturbing, frightening house calls went on and on and on.

“I kid you not: for a whole year we had people coming up every single week,” says Darren. “People would open the door and say, ‘Well, I guess I’m not gonna find who I’m looking for.’”

Moving to the storied home on Sly Fox Lane didn’t only bring the family in touch with strangers. It also re-connected Darren with someone he used to know.

“I had a friend from high school reach out to me,” says Darren. “She told me her son died of a heroin overdose—from this house here. He’d bought the drugs here.”

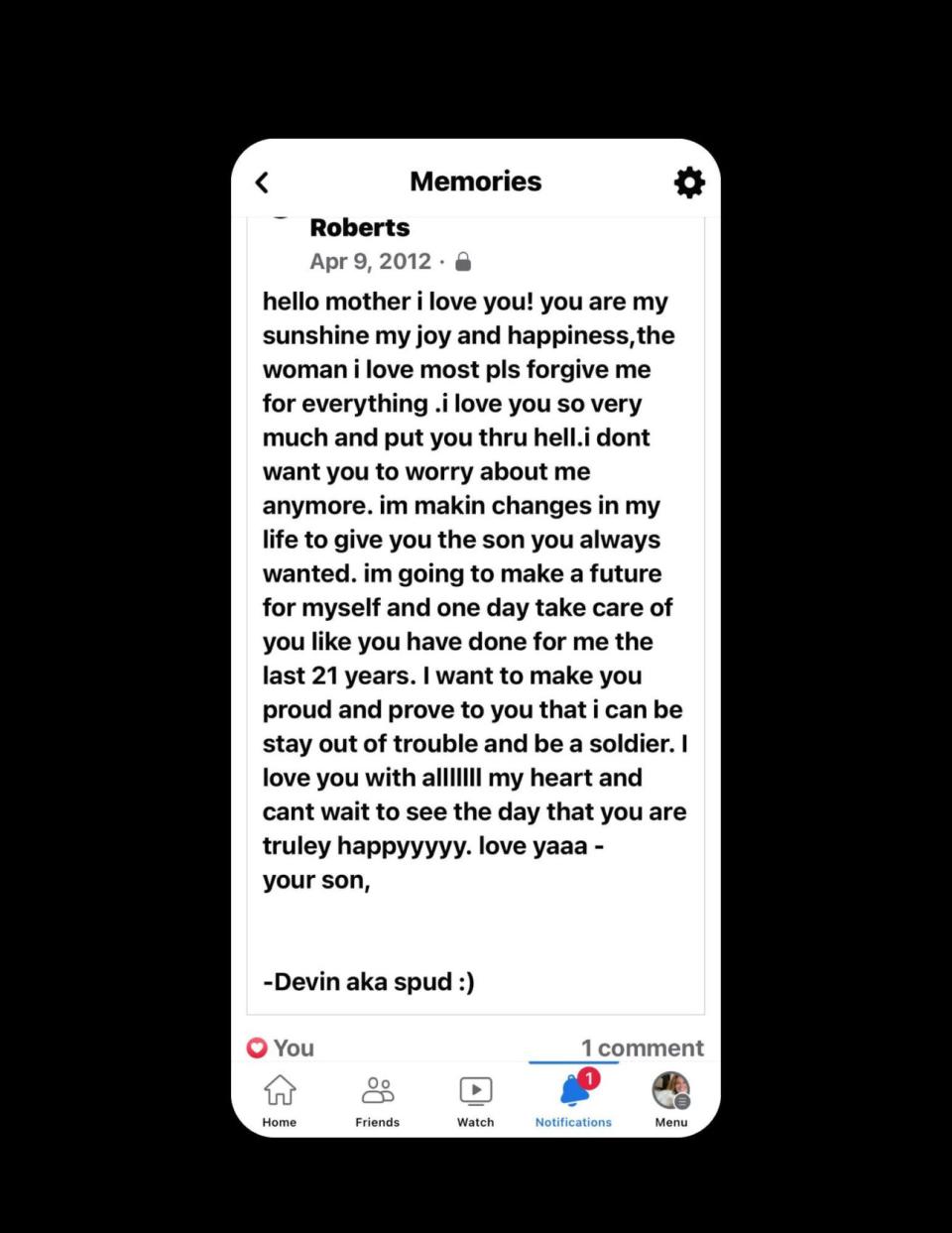

The grieving old friend was fellow Keedysviller Tracey Roberts, her dead son was named Devin, and when she reached out she wanted Darren to put his graphic design skills to use. “She asked me to do a t-shirt that said ‘FUCK HEROIN.’”

“That house was literally one mile from my house,” says Tracey, who hadn’t known what went down at Sly Fox Lane until she started following her son. “I was a hypervigilant mother.”

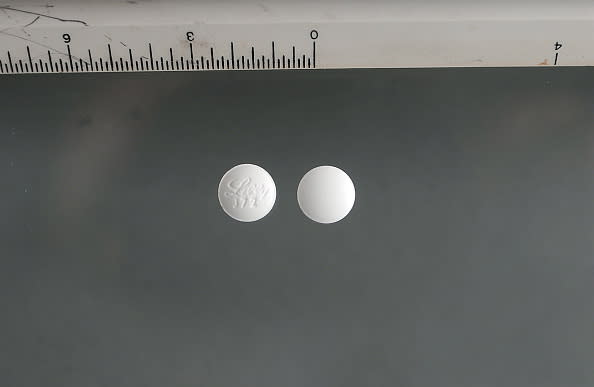

Her boy, Devin, had started high school in the mid-2000s as an active, healthy kid who played football and wrestled. When he got injured, however, the painkillers doled out were often opiates, and his medicinal use slid into recreational use. “At the time, kids were getting Percocets [oxycodone combined with acetaminophen] even at the dentist and then coming back to school with them,” Tracey says.

Late in Devin’s adolescence, his mother had a growing sense that something was wrong. “I started to notice a change in his friends when he was about 17. And when he finally graduated from high school, I was seeing more and more signs: him dropping weight; not eating very well; being very skittish on where he was going.”

Then Devin was badly hurt in a car accident. He was riding in the passenger side with his arm hanging out when a deer slammed into his door and shattered his elbow.

“I didn’t realize how far into drugs he was [already], but he started going and getting Percocets and other pills for the pain,” says Tracey. Their insurance with Kaiser Permanente only covered so much, and after two weeks she told Devin he was going to have to get off the meds. But by then—and even well before then, as she came to understand—his priority was his habit. And at $25 a bag, heroin was cheaper than pharmaceuticals.

With Tracey’s mom-radar now lighting up nonstop, she got on her son’s case big-time. “I was the mom in my kid’s cell phone, and saying, ‘Where are you going? Who are you gonna be with?’” She started tailing him and even making her presence felt. “I followed my son to that house. Until then I didn’t realize it was a drug house. But then, after I saw my son park there, it wouldn’t be uncommon for me to go right up to the door and be like, ‘You don’t need to be here.’ It was probably dangerous for me to do that but that was my boy. I was trying to save my boy.”

The situation deteriorated. Devin OD’d six times just in 2009 and 2010.

One night in 2013 Tracey was pet-sitting while Devin was out with a girl and a guy he used to wrestle. Towards midnight her phone rang with “that dreaded phone call the mother gets,” says Tracey. “The girl said, ‘Devin’s breathing funny.’ I have a background in nursing so I said to put the phone up to his face. He was sucking in air so hard it haunts me to this day. I said to call 911. When the ambulance got there he was very close to death: gray with blue lips. They reversed it with Narcan.”

Another time he was found collapsed outside a Subway in the rain. “He went in the bathroom, used, and by the time it hit him he was on the stoop. And somebody coming outta the sandwich place stopped and looked at him and he was blue and slumped over and the rain just pouring on him.” The ambulance station was just a stone’s throw, and yet again his life was saved.

His mother was chewed at by a constant expectation of the end. “Every day, you never knew when it was the last that you’d see your son,” she says.

I ask if they ever really discussed his brushes with death.

“Oh yeah. I was like, ‘Look, Devin, I’m your mother. I love you. Whether you’re good, you’re bad or ugly, and at this part of the game here, it doesn’t matter. You need to let me know what is going on so I can help.’”

Tracey talked him into rehab a couple of times, but the stays were generally only a fortnight and at first he didn’t take them seriously enough.

Eventually he did, however, not just saying he wanted to be clean but switching from junk to methadone, working productively as an electrician, and playing parent to his own baby boy, Levi.

Devin’s then-hometown didn’t have clinics offering opioid substitution, however, so to stay off the gear Devin racked up a shitload of miles and time. “He’d have to go about an hour away to get his methadone, so he’d get up at four in the morning to drop Levi off to me and be there [a methadone clinic in another town] by 5 o’clock, and then drive back to be at his job. For about two years he did that five days a week,” says Tracey. “My son wanted to get clean. He wanted to stay clean. He wanted to be a dad. He just didn’t have enough backing in the medical community, and enough resources. He didn’t have enough tools.”

Eventually he started using again, and again his mother found herself gripped by dread.

“I barely slept.”

Cutting Devin’s hair one time she found herself wanting to save a lock—as a future relic. “I knew I was gonna lose my son,” Tracey says. “It wasn’t a matter of whether I was or wasn’t. I knew without a shadow of a doubt—it was a matter of when am I going to get that call.”

Death circled.

“I lived every single day worried. I was always tracking him. Calling people and asking, ‘Have you guys seen him?’ ‘Yeah he just left here.’ And people knew to let me know he made it somewhere. It was the most earth-shattering time of my life because I was always on a pin-cushion waiting for a call.”

A network of family and friends kept tabs on Devin, keeping each other in the loop as to his movements and welfare as he lived in junk’s twilight. “This went on for four or five years,” Tracey says.

“Towards the end I saw it coming like a train wreck: like it was getting ready to happen. It was very surreal. He went through a lot of cars—Mustangs were his favorite. He wrecked a lot of cars because he was so high and would nod off.”

In his clean phases, Devin had spoken of wanting to set up a clean house—a home for young men like himself who needed to be clear of all drugs—but he’d relapse. Or he’d get on methadone but then through his spiraling misadventure be unable to stay on it and with it and in that grind and live to that discipline.

“About a week before he died he looked at me and said, ‘Mom, I have burned all my bridges and now I’m not sure how I’m gonna come out of this.’ He knew it. He knew that he had exhausted all jobs, all money, cars. Financially we were just buckled trying to keep this kid moving forward—trying to keep him in different programs to get clean.”

“That week,” says Tracey, her voice throaty. “That week I knew something was gonna go down. I had a little sparrow fly into my [car] window and hit me so hard it left a bruise. It was not a good sign. I knew deep in my gut that something was gonna come about. I told my kids that something was coming around the corner and it wasn’t good.”

It was late summer. Days hitting 90. And Tracey was right—it came inside a week.

“It was Sunday and I’d just come back from pet-sitting. My husband got a phone call from his mother’s house.

Devin’s father, Marty Roberts, listened and then told her that their son was in cardiac arrest and en route to hospital.

“I fell to my knees. I was screaming. The pit of my stomach totally dropped. I couldn’t even get on the phone.”

Tracey and Marty raced to the hospital, shaving well down what was an hour’s drive under normal conditions. “My husband was trying to be very optimistic, but I knew—I was like, ‘He’s dying. He’s dying.’”

“I walked into the emergency room,” continues Tracey, “and they had this machine that every time he went into cardiac arrest, would pump his chest. And I was greeted by a nurse that said, ‘You might as well disconnect—he’s not doing good.’ And I was like: ‘Disconnect? There’s no way I am gonna disconnect my son.”

The rush to unplug stopped when Tracey mentioned Devin’s status as an organ donor, she says. “Then they treated him like he wasn’t a drug addict.” Devin was moved up a floor, with a transplant team dispatched from Baltimore.

“What that did, Matt,” says Tracey, voice breaking, “was give me seven hours that I could hold my son.”

It also allowed time to call more family in to farewell the stricken young man. Furthermore, Tracey says the transplant team treated her with much more respect than the regular crew at the hospital, to whom she supposes Devin was just another addict exiting.

“What happened at the end?” I ask.

“I had to make the call,” she says. “They had a tube down his throat and it was filling up with blood. At that moment, you have to decide whether you want to see your child suffocate on his own blood, or to let him go. I chose … I chose to unplug him.”

Devin was 23. Tracey was 45.

“I was in shock that my baby wasn’t there,” Tracey says about the days that followed. “I stayed in my room. I wouldn’t come out. Sometimes I’d sit in his car.”

“My baby died, and it doesn’t … nobody else … everybody else …,” says Tracey, pausing to compose herself. “There’s no words that can give a mother any comfort. I didn’t want to breathe. I was like, ‘Why can’t I just go?’ I didn’t want to live. No mother should ever have to go through that.”

Then came the rage.

“It was a time in my life that I got angry,” says Tracey. “I got angry.”

She found kindred, agonized, grievously damaged spirits in Mothers Against Heroin, and she emblazoned her pick-up with “KILL HEROIN DEALERS.”

Did she want to hunt down the people who sold the drugs to her son, I ask.

“I did,” says Tracey. “I had his phone; I had numbers; I’ve been to the houses. I would call them up and threaten them, telling them “my son’s gone because of what you’ve done.” I went through every phone that my son had. I rode around town with KILL HEROIN DEALERS on the back of my truck—and I wasn’t ashamed, not one bit.”

Did the dealers and criminal element answer the calls, I ask.

“No. I got a lot of hangups and blocked calls,” laughs Tracey. “And I had to leave it, because I couldn’t find the guy that did this. I wasn’t sure which guy it was.”

And in her quest for vengeance, Tracey had come to feel even more alone. “It was like you were out there by yourself,” she says. “There were not very many people able to help you in the situation, and you were just walking through this earth and everybody else was doing their busy self and their life.”

On the occasion of Tracey’s first viewing of her boy’s dead body at the funeral home, she found herself hugged and comforted by another local woman and her daughters.

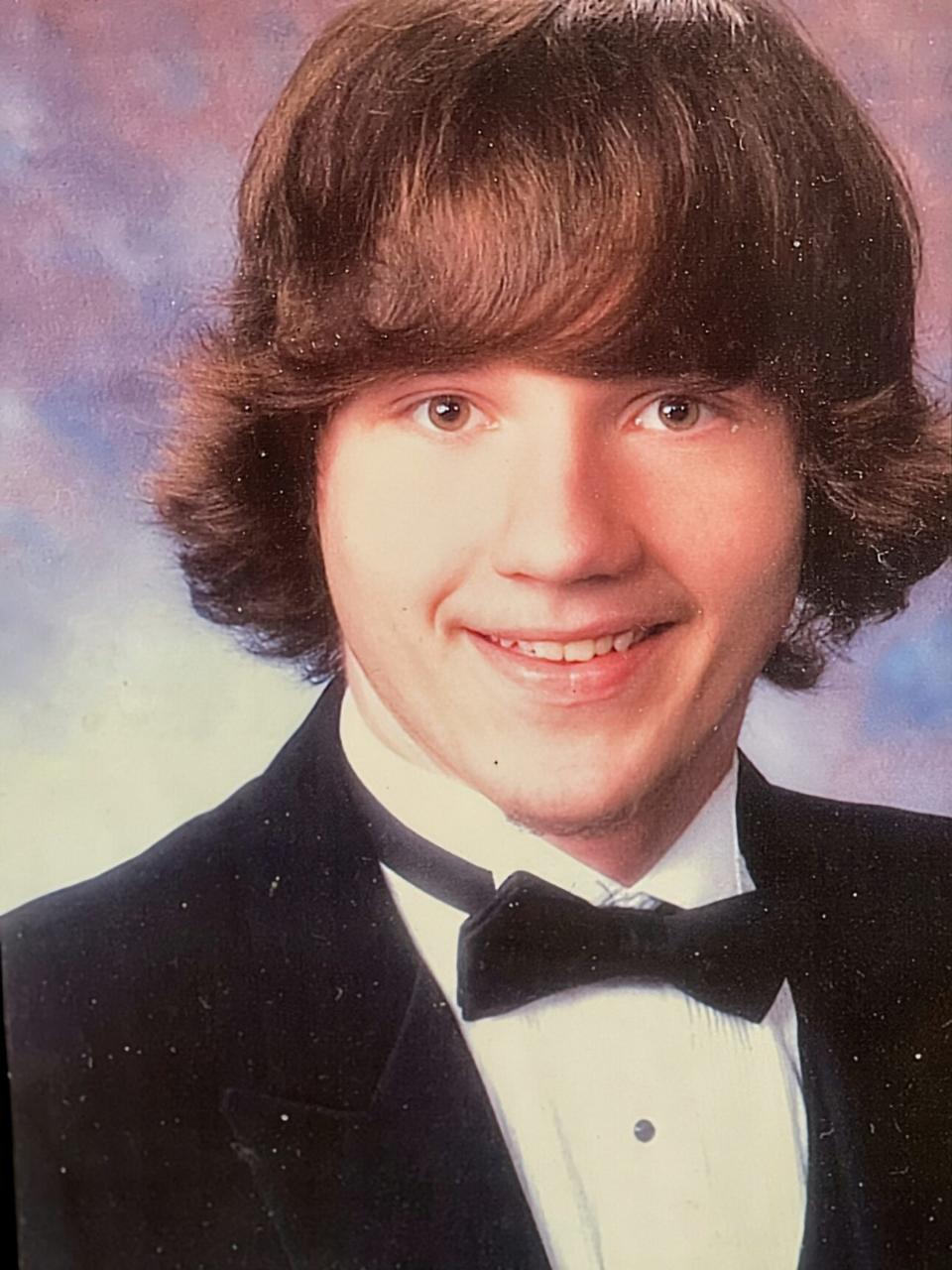

Confused as to why they were there, she learned that their boy, Gunnar Whipp—the woman’s son, the girl’s brother—was also lying in state.

Gunnar had fatally overdosed on heroin two days after Devin. Gunnar was just 20.

As Tracey got involved with Mothers Against Heroin and started her own grieving groups, she found herself sitting in a circle with a woman whose son she knew to have dealt dope to Devin—one of those death-peddlers that she had been burning to confront.

But there was no confrontation to be had, because this woman’s son was also dead. Another overdose.

“I realized that mother was just as hurt as me,” says Tracey.

Over time she learned to differentiate between addicts who deal to use—people not a world away from her son—and the non-using, profit-driven entrepreneurs of chemical slavery and death who move quantities from hubs like Baltimore to communities like Keedysville and through trap-houses like the one that Darren and his family bought on Sly Fox Lane.

Devin James Roberts was one of more than 53,000 fatal overdoses in America in 2015.

The body count has since accelerated and now exceeds 100,000 per year. As dangerous as heroin is, the great reaping has expanded over the past decade with the pervasive spread of potent semi-synthetic analogues—most notoriously fentanyl.

From the year of Devin’s death to now, drug overdoses have killed around 700,000 Americans.

When Tracey approached Darren Griffith in the wake of her son’s death, asking him to make her a t-shirt that said ‘FUCK HEROIN,’ he declined. Not being one for cuss words on clothes, he told her: “Let me come up with something that will honor your son’s memory a little bit better than ‘fuck heroin.’ You don’t want that to be his last memory.”

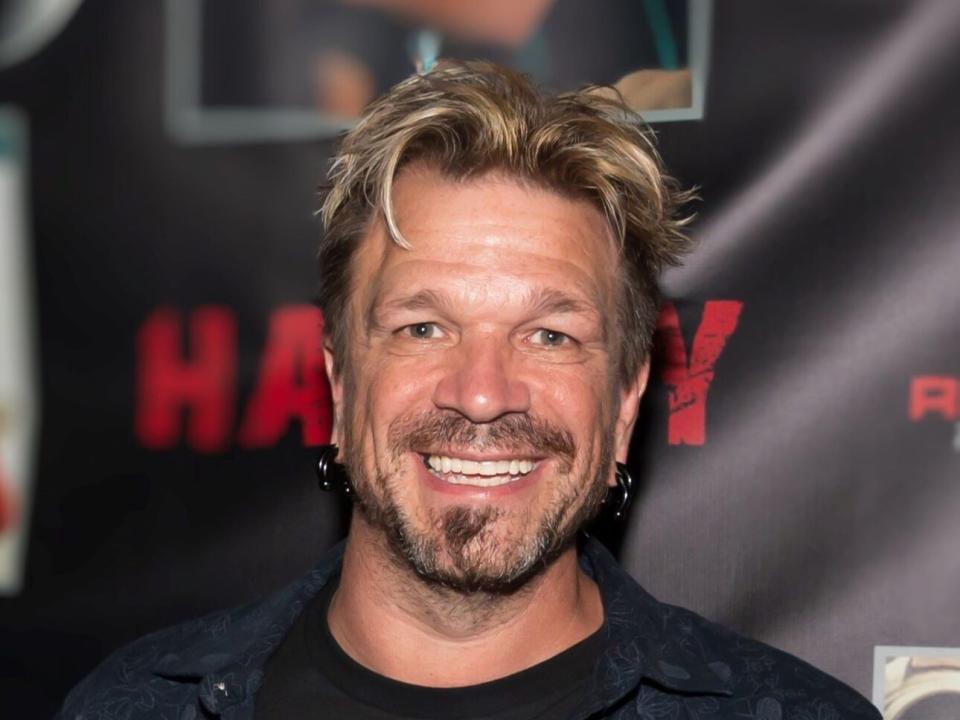

And thus was born the Lead Don’t Follow Foundation, a not-for-profit line of rock t-shirts and branded-events to which community-minded rockers and entertainers lend their names, images and performances, with sales and proceeds then going towards getting treatment for people who want to turn and run clear of America’s vast and expanding narco necropolis.

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.