This Arizona Town Has Some of the Best Stargazing in the U.S. — How to Plan a Trip

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Burgeoning Flagstaff is home to everything from science centers and stunning natural scapes to hip hotels and James Beard-nominated dining.

Kyle RM Johnson

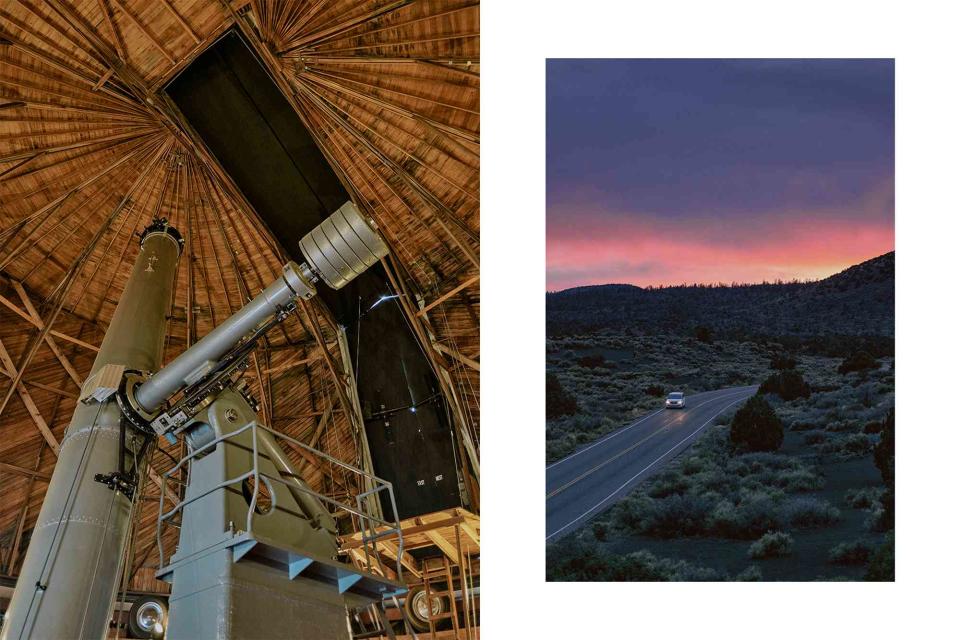

From left: The 24-inch Clark Refractor, one of the world's most storied telescopes, at the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona; the road to Sunset Crater Volcano.Mid-August, we learned soon after our arrival in Flagstaff, Arizona, is the height of monsoon season. While days were mostly sunny and, at an altitude of 7,000 feet, pleasantly temperate — especially when compared with the summer heat wave in Phoenix, a three-hour drive away — late afternoons and evenings were punctuated by fast-moving storms. One night our charmingly hip hotel, the High Country Motor Lodge, went abruptly dark in a storm-induced blackout.

My son Asher, a college student, began moaning about the sudden lack of Wi-Fi, and that’s when I realized this was a golden opportunity. I dragged him outdoors. The rain had stopped, and a brisk wind was dispersing the clouds that lingered around the San Francisco Peaks, pulling back the curtain on a vast, winking tapestry — pinpoints of light in an inky black sky.

Kyle RM Johnson

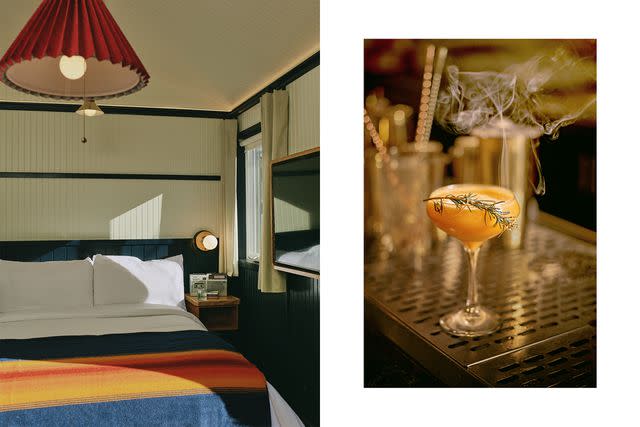

From left: A Cosmic Cottage suite at Flagstaff's newly renovated High Country Motor Lodge; the Old Ryder, a graham-cracker infused whiskey sour, at Atria.We had traveled to Flagstaff in part to reacquaint ourselves with the night sky. Home for us is New York City, which the Swiss architect Le Corbusier once described as “a Milky Way brought down to Earth,” a place where light pollution renders all but the brightest celestial bodies largely invisible.

Designated in 2001 as the world’s first International Dark Sky City, Flagstaff has been working to limit light pollution since at least 1958, when it passed an ordinance — remarkable in its foresight — restricting public illumination. It was prompted by scientists at the Lowell Observatory, a privately funded center for astronomical research founded in 1894 in what was then a mountain frontier town. Once Flagstaff received Dark Sky designation, the whole community came to recognize the importance of preserving its views of the stars. More subtle, perhaps, but no less powerful, was the influence of the nearby Diné/Navajo Nation, whose seasons and ceremonies have been organized around the constellations for millennia.

In the 1960s and 70s, the area’s lunar-like landscape of volcanic cinder cones, which remains sacred to Indigenous peoples, served as training ground for NASA’s Apollo astronauts. Flagstaff had a scruffy edge in those days, but today the town has a more youthful, optimistic feel, and a new generation of astronauts is training there. Artemis III (NASA’s first manned mission to the moon in more than half a century) is on track to launch next year.

Kyle RM Johnson

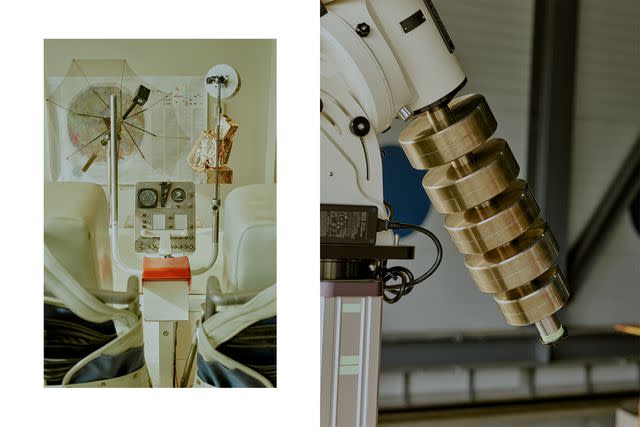

A test capsule used in training for the Apollo 11 moon landing on display at Meteor Crater.As a child, Asher was fascinated with astronauts and space rockets. Now a student at a major research university, he’s been channeling this interest into the study of physics and astronomy. My reference points, on the other hand, are mostly cultural. For me, “after dark” typically involves an art opening or a ballet; “Schiaparelli” makes me think of Elsa, the Paris-based fashion designer famous for the “hard chic” look of the 1930s, rather than her uncle Giovanni, the great 19th-century Italian astronomer. This trip would unfold on territory geographically new to both of us, but thematically more familiar to my son. Yet I welcomed this reversal of authority and the opportunity to learn more about a world that so captivates him.

Kyle RM Johnson

The Milky Way, as seen from Meteor Crater in Arizona.Our first stop was the Astrogeology Science Center, a branch of the U.S. Geological Survey founded in 1962 with a twin mission: to create geological maps of planets and other celestial bodies, and to train astronaut candidates (a.k.a. AsCans) in the rock science they would need to effectively prowl the moon’s surface. The center, which is open to the public by appointment, offers scientist-led tours.

This was geek heaven for Asher, who got to speak with specialists in planetary defense (news flash: no known asteroids are on track to hit Earth) and space resources (evidently ice on the moon’s polar caps is stirring up a lot of interest). We also learned that during fieldwork expeditions, the AsCans are really good campers (highly motivated and collaborative, with a can-do attitude).

After gaping at Grover, the rover used in Apollo astronaut training, and working up an appetite by striding across the center’s topographical floor map of Mars, we headed downtown for lunch at Proper Meats & Provisions, a combination butcher/sandwich shop that serves locally sourced, humanely raised meats in a historic building on Route 66. No shade intended to my favorite Lower East Side deli, but their James Beard-nominated pastrami was in a class of its own.

Kyle RM Johnson

The pastrami sandwich from Proper Meats & Provisions; shopping the deli counter at Proper Meats & Provisions.That afternoon, at the jewel-like Museum of Northern Arizona, we began learning about the culture and history of the 10 Indigenous tribes of the Colorado Plateau. Here, tribal consultants have collaborated on displays of exquisite pottery, basketry, and dress by Hopi, Yavapai, and Zuni peoples, among others. The following morning we had a very different out-of-this-world experience: viewing the sun at the Lowell Observatory. Staring through a telescope fitted with a safety filter at an orange orb ringed with dancing tendrils — the source of much of the heat, light, and warmth on Earth — I felt as if I might be looking directly at a god.

Percival Lowell, the Mars-obsessed scientist who founded the observatory on a hillside covered in ponderosa pine, is buried in a domed mausoleum on site. Jeffrey Hall, Lowell’s current director, pointed it out on a quick tour of the research facility’s picturesque campus, which also preserves the structure where in 1929, Clyde Tombaugh, a former Kansas farm boy, gazed through a 13-inch telescope and spotted something that led to the discovery of Pluto. (Despite Pluto’s 2006 demotion to “dwarf” status, many here still consider it a full-fledged planet.)

Kyle RM Johnson

From left: The interior of Grover, a geologic rover at the Astrogeology Science Center; a telescope on display at the Lowell Observatory.Big changes are afoot at Lowell today, including the completion, later this year, of a giant, $53 million open-air planetarium, with heated seating for the chilly nights when Flagstaff’s dark skies will be the main spectacle.

Hall agreed to meet us in his cozy Arts-and-Crafts-style office, where we discussed the challenges facing observers of the heavens today. One of these is the proliferation, since 2019, of Starlink satellites, which, while facilitating global communications, also risk transforming the views of “low Earth orbit” (300 to 1,000 miles up). This has the potential to affect both astronomers and the Indigenous populations “whose oral traditions and cultural heritage are in the stars,” as he put it. “It would be like rewriting the Bible for us.”

Kyle RM Johnson

The General Store Bar & Lounge at High Country Motor Lodge.Meanwhile, back on Earth, we are facing a watershed moment for light pollution, whose deleterious effects on both human and animal life are gaining increasing attention. Communities around the world, Hall said, are switching from legacy lighting systems to more cost-effective LEDs, but in doing so they risk doubling sky glow. “Already, three-quarters of the people in the United States can no longer see the Milky Way,” he added. Flagstaff’s streetlights use amber LEDs that are directed downward, protecting the city’s dark skies. “We are trying to establish a model that other communities can use,” Hall said.

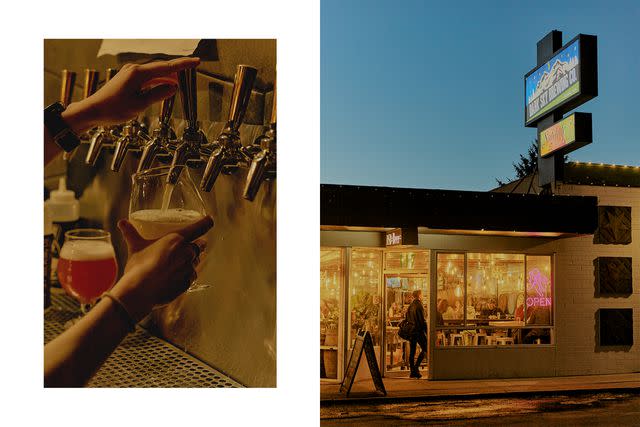

What do we lose when we take away the night, with our insistent focus on a 24/7 work cycle and on illuminating, well, just about everything? These were my thoughts on an evening walk through the amber-glowing streets of downtown Flagstaff after pizza and craft beers at local favorite Dark Sky Brewery & Pizzicletta. Our guides were Chris Luginbuhl, an astronomer and president of the Flagstaff Dark Skies Coalition, and Danielle Adams, a scholar whose research has focused on ancient Arabian star lore. Adams explained the derivation of names like Aldebaran, which comes from the Arabic “al Dabarān,” meaning “the Follower,” because this reddish star appears to “follow” the Pleiades cluster across the night sky. As she spoke, it struck me that the rich human history attached to the stars is also now in danger of extinction.

Kyle RM Johnson

From left: Local beers on tap at Dark Sky Brewing Co.; Dark Sky Brewing Taproom & Pizzicletta, in downtown Flagstaff.The skies were slowly clearing as we headed back up Mars Hill for a late-night astronomical “snack” at Lowell, where we took in a glorious view of Saturn and its rings, an image of celestial perfection.

Still, it was only the next day, while hiking the beautiful, isolated Lava Flow Trail along Sunset Crater Volcano, where Indigenous people continue to worship and the Apollo astronauts once roamed, that our urban reflexes began to fall away, replaced by a sense of wonder. At Wupatki National Monument, 15 miles to the northeast, we entered another time zone, both literally — because the park shares boundaries with the Navajo Nation, which unlike Arizona observes Daylight Saving Time — and figuratively, as we observed the spectacular ruins of pueblos built by ancestors of the Hopi and Zuni tribes almost 1,000 years ago, amid a landscape of desert scrub and red rock.

Kyle RM Johnson

Meteor Crater, about a half-hour outside Flagstaff.The following day, while standing on the upper rim of Meteor Crater and spotting Asher, a tiny dot on an observation deck far below me, I had an inkling of the vastness of worlds beyond Earth. The crater, three-quarters of a mile wide and as deep as the Washington Monument is tall, was formed more than 50,000 years ago when a meteor traveling at 29,000 miles per hour hurled itself into our planet. (The Barringer Space Museum, on site, offers engaging, interactive — and at times, physically jolting — displays on meteors and their impact.)

That evening, in recovery mode, we treated ourselves to chef Rochelle Daniel’s refined American cooking at Atria with hot and cold oysters, bone-marrow tartare, house-made pasta, and Sonoma duck breast. We were also gathering strength for the next day’s adventure: stargazing at the Grand Canyon.

As daylight waned the following evening, the hordes of tourists around the canyon’s South Rim quickly dissipated. Our guide, an astronomer from Grand Canyon Adventures, had brought along a small telescope, and while the light was still strong enough, he trained it on the Colorado River, a thin, glittering vein of silver on the canyon’s bottom.

Kyle RM Johnson

Sunset Crater, the site of Arizona's most recent volcanic eruption.A pair of elks and a lone bighorn sheep, straying from their herds, had wandered up to the rim to enjoy the sunset with us. In the deepening twilight, a little train of satellites, visible to the naked eye, traced a diagonal line against the mauve sky. And then night fell. It took a while for our vision to adjust, but soon we spotted the first of what would turn out to be dozens of brilliant dashes in the darkening canopy overhead — the Perseids meteor shower.

Today I can remember only a few names of the stars and constellations we saw that evening. But I will never forget the awe we felt as we watched the Milky Way rising over the North Rim — a giant, luminous path, leading to an unknown destination.

A version of this story first appeared in the April 2024 issue of Travel + Leisure under the headline "The Light Fantastic."

For more Travel & Leisure news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on Travel & Leisure.