Agnes and Catherine Gund on Effecting Radical Change Through Art

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

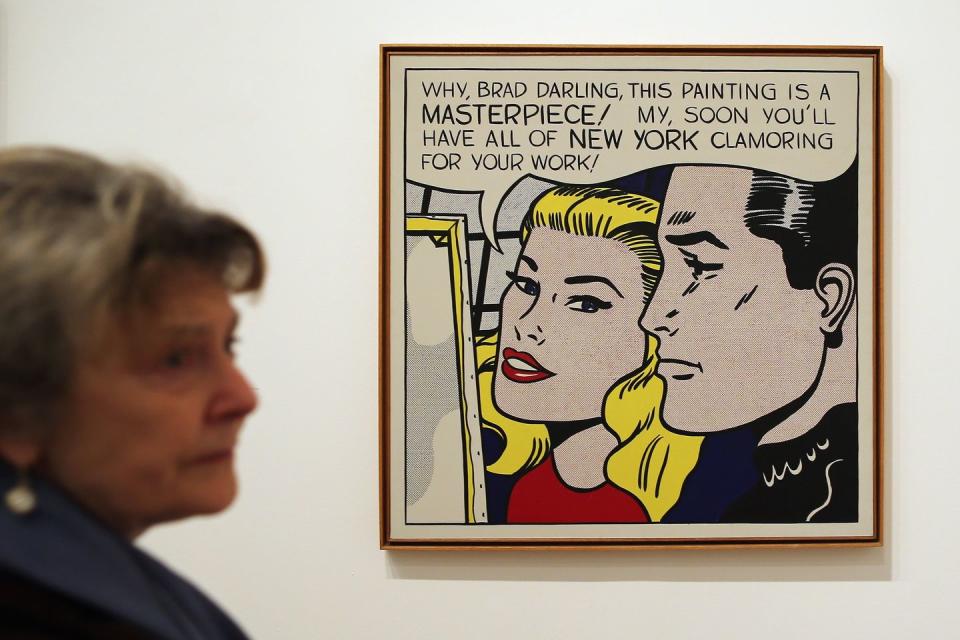

I never thought 1960s Pop artist Roy Lichtenstein would be mentioned in the same breath as ending mass incarceration in the United States. I certainly never thought a figure as large as $127 million would find its way to a movement for and led by people impacted by our criminal legal system. But that’s what Agnes “Aggie” Gund does. She merges worlds.

After seeing Ava Duvernay’s critically acclaimed 2016 documentary 13th—an examination of the harmful impact of the 13th Amendment, which permits slavery as “punishment for a crime” inside of prisons—the art collector and philanthropist (and perhaps the “last good rich person”) enmeshed herself in the call to decarcerate. In 2017, Aggie took Lichtenstein’s 1962 Pop art painting Masterpiece off of the mantel in her Manhattan apartment, sold it for $165 million, and used the proceeds to launch the Art for Justice Fund with her daughter Catherine. A spend-down initiative, A4J distributed 450 grants over its six-year tenure to artists, community projects and programs, and organizations whose work, in some form, addressed our country’s carceral crisis. There were no specific stipulations to receive a grant, so long as grantees’ work informed the mission to reduce mass incarceration through either legal or narrative change. Most recipients had been impacted directly by the system themselves or indirectly through their communities.

From day one, the Gunds sought to disrupt the hierarchical, transactional nature of philanthropy. Regarding A4J specifically, this meant saying goodbye to typical donor events and instead putting all participants—from legacy millionaires to artists and people recently released from prison—in the same room, consistently, as peers, not saviors or otherwise. It meant Aggie interacting with work inside San Quentin correctional institution in the same vein as what’s shown at the MoMA. It meant bringing (at the time) emerging artists like Jesse Krimes (who recently signed with Jack Shainman Gallery) and Russell Craig, who both spent time inside, along to studio visits with contemporary artist Mark Bradford. (The three built a long-standing relationship, and Bradford consequently became the first artist to donate work that raised $1 million for A4J.) It meant ongoing celebratory dinners, destination conferences, and shows that quite literally featured love in the title—all of which continuously communicated this was a group of people with a shared goal who could reach successful movement markers only in relationship with one another. This was a big part of what A4J ultimately coined its “special sauce.”

Another part of that special sauce was A4J’s level of care, which seemed to stem from both its ethos—repairing egregious harm caused by the criminal legal system through a combination of art and community organizing—and its foundation as a family affair. “Our children are always our biggest motivator, so to do such important work side by side with my daughter is the ultimate validation,” Aggie says.

We’re in her living room on New York’s Upper East Side, and she’s seated next to Catherine, a filmmaker and activist. In the wake of A4J’s closing last June, we’re there to discuss the fund’s impact, but it feels like we’re at the Gunds’ dinner table: A daughter playfully interrupts her mother mid-thought, a mother comments on how she doesn’t like the frayed hems of jeans that are among her kids’ (and my own) latest style choices. I left our two or so hours together not reflecting on Aggie’s high-ceilinged, expansive home that reads like a museum—but on the fact that she and Catherine held hands nearly the entire interview.

This subtle yet consistent connection between the mother and daughter is a through line of their relationship—encompassing public displays of affection, like Catherine directing and producing a feature film on her mother, Aggie, in 2020, as well as more personal memories, like coming out to Aggie. “Her curiosity [comes] before judgment,” Catherine says. “I had thought that when I came out, she wouldn’t be affectionate with me anymore, she wouldn’t hug me—there was no reason I thought that … other than society telling me I was gross.” When she came home from college after first coming out, she says, she remembers Aggie lying in bed while talking, and then summoning Catherine in to hug and hold her. “It was the first time we had a physically caring moment since I had come out, and I remember being so relieved,” Catherine says, small tears beginning to well in her eyes. “It was a deepening of our connection, and from then on I knew I was hers. I knew she was there—and she always has been.”

And just as much as Catherine feels she is Aggie’s, Aggie is Catherine’s. Asked why she let her daughter make a movie about her, Aggie turns to Catherine and says, simply, “Because you’re you.” The film covers the art philanthropist’s body of work—from launching the visual arts program Studio in a School to nurturing relationships with artists like Thelma Golden and Hank Willis Thomas. It also sheds light on how Aggie showed up for Catherine’s activism in response to the AIDS crisis and calls for queer liberation; a standout scene features Aggie joining Catherine in a 1989 Pride parade with members of PFLAG, an organization that focused on bringing together parents and loved ones of queer folks. “These were people like me,” Aggie says. “People who loved their kids, who didn’t have a problem with their children—but with the world that says they’re not okay.”

Catherine and Aggie’s familiarity and tenderness emanate throughout A4J’s work, even down to their funding. Alongside institutional support from Ford Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation, A4J chose a reparations model in which money goes straight into the hands of the artists, org leaders, and other grantees directly impacted by or proximate to incarceration, who then decide how the work evolves. “The fund’s ethos was not to pretend that we know how to make the art or do the advocacy ourselves,” Catherine says. “It was to put together an incredibly brilliant, dynamic group of staff members of different expertise and backgrounds to bring it all together.” She poetically likens this approach to how one might support an artist: “You don’t fund an artist because you hope they’ll make more blue paintings, specifically; you fund them so they will develop their work.”

That work was expansive. A4J’s 212 grantees include 130 organizations and 82 individuals. Artists and abolitionists Aimee Wissman and Kamisha Thomas established a dedicated space for the Returning Artists Guild, their Ohio-based organization that supports directly impacted artists and extends from work begun when the cofounders were inside Dayton Correctional Institution. Halim Flowers started his eponymous fashion brand, alongside his many artistic endeavors denouncing the Hillary Clinton–popularized terminology superpredator. Die Jim Crow Records, the first label in the United States for systems-impacted musicians, released its first two full-length albums to critical acclaim. Haymarket Books started a fellowship dedicated to writers impacted by incarceration. The list goes on. On its new website, A4J traces more of the fund’s impact, including key policy wins like Worth Rises’ victory securing legislation for free phone calls for incarcerated families in New York, Connecticut, Colorado, Texas, and Minnesota. It also features a graph sourced by the Vera Institute of Justice that examines declining incarceration rates in A4J priority states from 2016 to 2021.

Of course, Catherine and Aggie both acknowledge that there is much more to be done. The fund started against a political backdrop that Catherine deems a “magical window in history” in hindsight, when it seemed people were beginning to acknowledge the evolution of slavery to incarceration. As Catherine says, “there was an emergence of and reliance on formerly incarcerated leaders, a bipartisan effort to decarcerate, and the narrative was starting to change.” Whereas now, we’re looking at a Democratic mayor, Eric Adams, pumping money into New York’s transit cop force and questioning the closing of Rikers Island. But while steadfast in their understanding that heavy lifting to end mass incarceration must continue, the Gunds also proudly reflect on the expansive, somewhat unexpected network of creatives, advocates, and funders that has emerged from A4J’s six years. “You don’t find that anywhere else—people with such a range of experience that are all on the same playing field,” Catherine says.

Upon A4J’s closing, organizations like the Mellon Foundation (which last year launched Imagining Freedom, a $125 million initiative similarly committed to artists, curators, educators, and other creatives directly impacted by incarceration who are driving lasting change) and the Just Trust (a fund dedicated to “visionary leaders and organizations fighting for the safety and well-being of their communities,” per its website) continue to focus on efforts to end mass incarceration that span the spectrum of reform to abolition. As for the Gunds, their work also continues. This year, Catherine will debut Paint Me a Road Out of Here, a film produced by her nonprofit Aubin Pictures that weaves the lives of artists Faith Ringgold and Mary Baxter with those of the many women seeking freedom from Rikers Island over the last 50 years.

In 1971, Ringgold was commissioned by MoMA to make a piece for the Women’s Center on Rikers Island. When she asked what they wanted to see in the painting, one woman inside said, “I wanna see a road leading out of here.” One of the film’s plot lines follows the painting—which, at one point, was discovered by a correctional officer completely painted over in white water-based paint—and how its treatment is an allegory for the inhumane treatment of women inside prisons and jails. The other storyline, which merges and overlaps with Ringgold’s and the women’s inside Rikers, follows Baxter’s life as an artist whose work often speaks to her experience being incarcerated. One of the closing scenes mirrors the vote for the Brooklyn Museum to safely house Ringgold’s painting with the Board of Pardons’ vote to expunge Baxter’s record.

At 85, Aggie will not be founding another “Art for” entity, but Catherine says her mother’s advocacy will not stop. “She’s functioning in so many arenas, she does more than even I know, and I know more than anyone else knows,” the younger Gund says. Aggie has already sold another Lichtenstein to support the Groundswell Fund for reproductive rights, and she says she is also focused on gun control. But this doesn’t mean her attention to mass incarceration, and its interconnectedness with other issues (think: criminalizing abortion), has ended. In Catherine’s words, “she’s going to keep doing what she’s always done, focused on the same things: humanity, safety, and agency.”

You Might Also Like