From Post archives: Allman Brothers' Dickey Betts and his early years in West Palm Beach

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Editor's note: This story originally published in The Palm Beach Post newspaper in 1995. Dickey Betts, who wrote and sang the Allman Brothers Band’s No. 1 hit "Ramblin' Man," died at his home in south Sarasota County on Thursday, April 18. He was 80 years old.

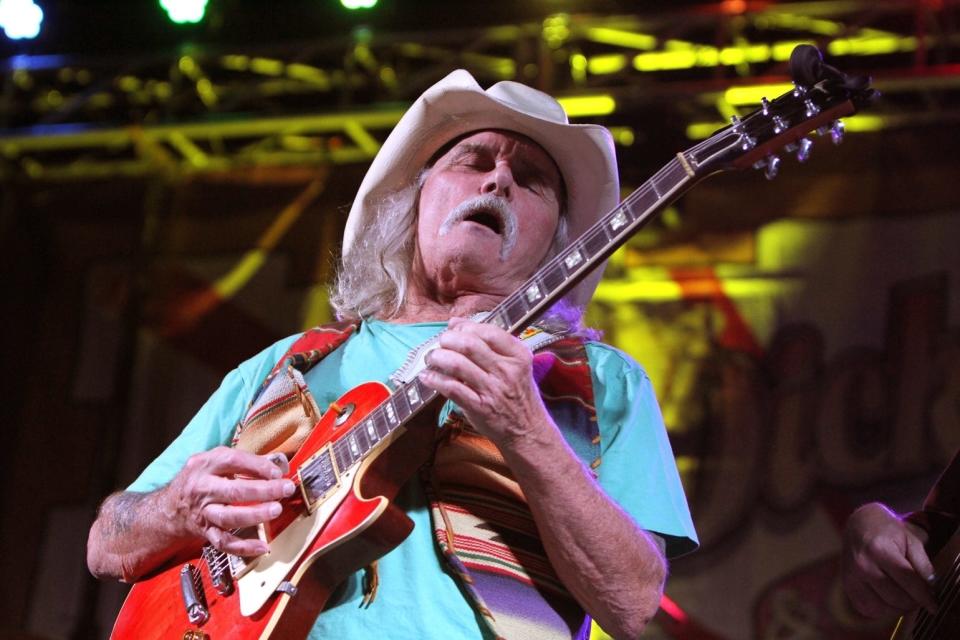

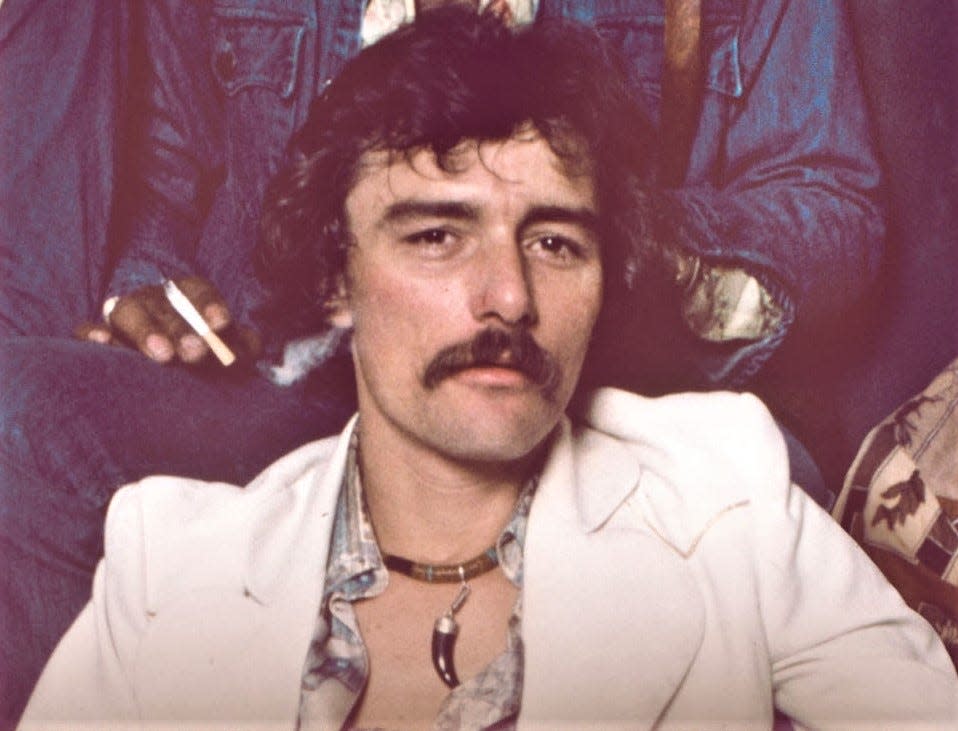

The weather-beaten cowboy hat was pulled down low over his head, leaving his eyes in the shadows. The only visible parts of Dickey Betts' face were his square jaw and the pointed ends of a dark moustache that curled around his upper lip.

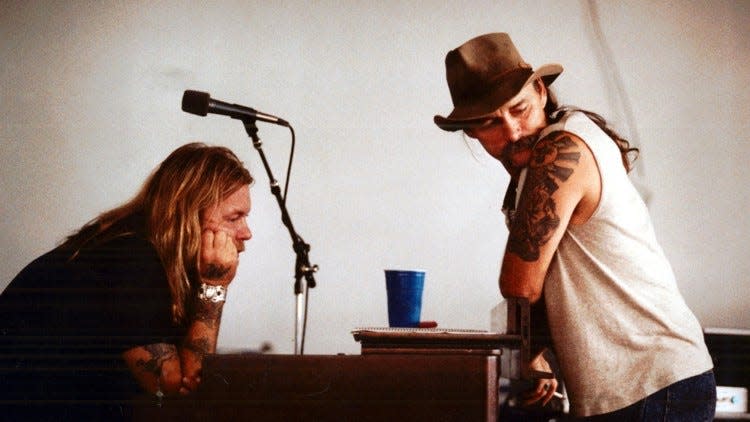

He was leading the rest of the Allman Brothers Band through rehearsal of a new song, "Back Where It All Begins," in a dimly lighted West Palm Beach club that could barely contain all the band's amps, speakers, audio monitors and equipment cases.

Betts approached his microphone and in a clear, sparkling voice sang, "When I was younger I was hard to hold / Seemed like I was always going whichever way the wind would blow / Now that traveling feelin' calls me again / Callin' me back to where it all begins.''

The song was nine minutes and five seconds of high-flying exhilaration, swinging guitars and waves of rollicking rhythm. The band — organist-singer Gregg Allman, drummers Butch Trucks and Jai Johanny "Jaimoe'' Johanson, guitarist Warren Haynes, bassist Allen Woody, percussionist Marc Quinones and Betts — would spring it on area fans a few days later during a three-hour show at the Heritage Festival in November 1993.

The tune had the emotional heft and inspired playing of other songs that Betts has contributed to the band's classic catalog: "In Memory of Elizabeth Reed," "Revival," "Blue Sky," "Jessica," "Crazy Love," "Duane's Tune," and the band's biggest hit, "Ramblin' Man." That song reached No. 2 on the Billboard charts in 1973 and has been aired in the United States an average of 80,000 times a year since. Those songs are part of the reason Betts and the Allmans are being inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame tonight (Jan. 12, 1995) in New York.

For Betts, rehearsing in West Palm Beach back then was fitting: It took him back to where it all began.

Forrest Richard Betts was born at Good Samaritan Hospital on Dec. 12, 1943. He grew up in "a shotgun house'' in the Westgate section of West Palm Beach, a poor neighborhood he describes as "an isolated little burg.''

Four-year-old Dickey would try to strum along on his ukulele while his father and uncles wailed away on fiddles, dobros and guitars playing "square dance music.''

Betts' father, Harold, a carpenter who helped build the Belvedere Homes development, was an adroit fiddle player. His mother, Estora, wrote poetry and played coronet in the local Salvation Army band.

"I never could play the fiddle,'' Betts recalls during a interview about his Palm Beach County roots. "I played the ukulele and the mandolin — which is really a fiddle you play with a pick. Then I took up the banjo.''

After a while, "He was better than we were,'' says Dickey's uncle Floyd Jiggs'' Betts, a 73-year-old Lake Worth resident who played guitar during those afternoon Westgate jam sessions. "I told a lot of people before he made it big that my nephew was the best guitar player I'd ever seen in person and was good enough to make a living at it.''

Betts wrote his first song and performed it for his third-grade class at West Gate Elementary School (where he had a crush on Mrs. Mondel, his teacher). The song was called "Seven Years With Pamela." It was about his sister, not Mrs. Mondel.

"I must have been a cute little cuss with that ukulele,'' Betts reminisces. He attended West Palm Beach schools into the seventh grade before the family moved to Sarasota to find work.

On weekends when he wasn't playing music, he was sneaking into baseball games at Connie Mack Field, swimming at the YMCA with his friends and listening to the Grand Ole Opry on the family radio. That was "big time excitement'' in West Palm Beach in the '50s, Betts says.

Betts also was becoming an accomplished woodsman, bow hunter and carpenter. He and his older brother Joel often would hunt rabbits for dinner.

"We went hunting to help with the grocery bill,'' Betts says. "We were taught at an early age that you just don't kill to shoot something. You kill two or three rabbits and that's it. If we brought home five or six, there was hell to pay. We learned some real valuable woodsmanship and how to respect the environment when that wasn't in vogue.''

Dickey Betts' early inspirations

His musical tastes began to change when he heard Chuck Berry at about age 12. Berry's "Maybellene" was on the radio. Betts switched from mandolin and banjo to guitar a couple of years later. The reason was simple: "Around 14 or 15, I started realizing girls liked guitars.''

Betts became enamored of guitarist Duane Eddy, and later blues guitarist Freddie King, learning their music note for note. From then on, says Betts, "I was a rock 'n' roll baby.''

He dropped out of high school in Sarasota at 16 because his band, the Swinging Saints, got a job with the World of Mirth Fair touring the U.S. and Canada.

"We put on a hell of a show,'' Betts recalls. "We did 30-minute sets all over the country. What an education traveling with carnies and learning how a group sticks together and looks out for each other.''

Those lessons would come in handy in Jacksonville, a city Betts frequented and the place where the Allman Brothers Band was born in 1969.

"Jacksonville was always the place to go when you were out of work,'' Betts says. "You could always get work at a bottle club. . . . You were guaranteed $100 a week and all the women you could pick up. We called it Jackass Flats: It was a redneck rough-ass town, a navy base where long hair wasn't looked upon too good, especially late at night. I learned how to brawl in the streets and play the blues in Jacksonville.''

But there's much more than the blues in Betts' playing and composing. His songs are almost classical in structure. He admits to listening to Brahms violin concertos and also has a passion for Charlie Parker.

It was that sound and sense of composition that Betts added to what would evolve into the Allman Brothers Band.

Betts was playing with bassist Berry Oakley in a Jacksonville band called the Second Coming when Duane Allman arrived in town. Allman wanted to enlist Oakley for a band. Oakley persuaded him to include Betts after hearing some magical jamming between Allman and Betts.

"(Duane's) style was real definite, and mine was, too,'' Betts says of the pair's musical chemistry. "We didn't copy each other. We didn't need each other. We were opposites. He had a stinging, spitfire trebly sound, and I had a B.B. King-Freddie King sound. I milk the notes longer. It was a real unique thing.''

The first song Betts contributed to the Allman Brothers would become one of the group's signature tunes and a confidence-builder for him. It was called "In Memory of Elizabeth Reed." Betts modestly calls it a song that has "weathered the years,'' and says that, "With 'Reed,' I saw my writing could be viable.''

There was no Elizabeth Reed in Betts' life. But there was a Carmella. Problem was, Carmella was living with Boz Scaggs — and seeing Betts on the side.

"I couldn't call it Carmella or Boz would be all over me,'' Betts says. "I used to write by a graveyard in Macon. `In Memory of Elizabeth Jones Reed, Mother of . . . ' was on a tombstone. Enough time has gone by so I can start telling people.''

Cemeteries and other solitary places such as the Alabama woods, Arizona desert and Alaskan wilderness influence Betts' music.

"There's lots of quiet time; there's lots of musical ideas out in the woods,'' Betts says. "It's a nice place to reflect. You sit in the same place for two hours or so and watch different wildlife and things. Some people like going to the beach and sitting. I really enjoy the woods. I almost get lost.''

Back on track for Dickey Betts

Like other members of the band, Betts got lost in alcohol and drugs. "Back Where It All Begins" signaled a passage for Betts, and the West Palm Beach rehearsals in 1993 were held shortly after Betts finished a three-month treatment.

With "Back Where It All Begins" and the blues confessionals "Everybody's Got A Mountain to Climb" and "Change My Way of Living," Betts reclaimed higher, more solid ground.

(All those songs are on the group's latest album, which was recorded at Burt Reynolds' Jupiter ranch.)

And now comes the induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. What could be more solid or enduring? Betts calls it, "The final golden seal on a great career. We know we've been influential, but to have this distinguished panel vote us in on the first ballot is an honor."

Though Charlie Daniels immortalized him in song, few fans probably know Betts penned "Ramblin' Man" and others. His playing is an inspiration and model for many young guitarists, but his name is rarely mentioned with other great players.

That's partly because of his disinterest in self-promotion, aversion to the media and blue-collar approach to his music. Not to mention the burden of living in the long, ghostly shadow of band mate, friend and guitar giant Duane Allman, killed in a motor-cycle accident in 1971. (Oakley died the following year in a similar accident.)

Even when out on his own, Dickey was never that much of an egotist to develop a charismatic character,'' says Allman Brothers producer Tom Dowd. He was always a member and leader of a team. That's where he's comfortable. He feels secure in knowing he doesn't have to be it every day.

Simply put, Betts doesn't fashion himself a star.

He lives with his third wife, Donna, and Duane, one of his four children, outside Sarasota in a ranch house on 40 green, wooded acres along a river bank. Friends and family call the secluded homestead Nowhere, U.S.A.

And that, says a relative, "is the way he wants it.'' Back in the woods away from the hustle and temptation, where he can smell the morning dew and wrap himself in friendly solitude. Back where it all begins.

Among legends of music at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

The Allman Brothers will be in good company at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame's 10th Annual Induction Ceremony tonight at the Waldorf Astoria hotel in New York.

Also being inducted are: gospel-soul singer Al Green, Janis Joplin, Led Zeppelin, Martha & the Vandellas, Neil Young and Frank Zappa.

The Orioles are being inducted in the early influences category.

Music journalist Paul Ackerman is being inducted in the non-performer category.

Florida residents already in the Hall of Fame include Dion (Boca Raton), Byrds co-founder Roger McGuinn (Orlando) and Bo Diddley (Tallahassee).

Acts are eligible for induction 25 years after the release of their first record. The voting body is comprised of about 600 music industry movers and shakers, broadcasters and journalists.

The Rock And Roll Hall of Fame and Museum is scheduled to open Labor Day weekend in Cleveland, the city in which deejay Alan Freed is said to have coined the term ``rock and roll.''

This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Post: Dickey Betts dead: Ramblin Man feature from Post archives