Fallout Review: Lucy N’ This Guy, With Dyin’ Man

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

For all the pointed critique of end-stage capitalism in Fallout – both the new Prime Video series and the video game franchise it’s based on – it sure is a merchandise mover in and of itself. Within the show itself, plastic bobbleheads of smiling mascot Vault Boy survive the nuclear apocalypse; in our reality, they probably will as well. The notion at the heart of the property is that big business will not only market the end of the world but prevail enough, cockroach-like, to continue to turn survival into a franchise via branded Vaults. All decked out in a blue and gold color scheme, suspiciously similar to Walmart’s…and Amazon’s.

Yes, the actual corporate entity with the smile logo, the one that all but monopolizes mail-order and confines employees to massive warehouses full of products, brings you this show critical of massive corporate vaults filled with everything a person needs, where humans are trapped for a near-eternity surrounded by smiling mascot images. What’s that apocryphal Lenin quote about capitalists selling you the rope to hang them with? In actuality, it’s vice versa – idealists will create more consumers by commodifying their critique.

It’s All About Control

Not that communism, by any other name, fares any better in the world of Fallout, which overtly blames anyone who wants to design a top-down, centrally-controlled society for the destruction of said society. That, at least, appears to be the TV show’s understanding of the game’s tag line, “War never changes,” a simple enough phrase that it can mean anything and nothing, and looks good on a T-shirt.

The embodiment of good in Fallout, rather, is Lucy MacLean (Ella Purnell, just the right amount of peppy), a Vault-dweller in search of her dad (Kyle MacLachlan). Raised in a safe Vault, she constantly cites and lives the golden rule of doing unto others as you would have them do unto you. Jesus may not be mentioned by name, but Lucy represents Christianity’s most essential doctrines in word and deed, though the show strongly suggests that a person can only be so naive as to do so if they come from privilege. The dramatic tension comes less from whether or not Lucy will die or get hurt, though that’s there, but whether she’ll have to compromise her principles once she’s removed from her safe, cultish community of like-minded folks and thrown into Mad Max territory up above.

Boils and Ghouls

Lucy’s counterpart, her Satan in the wilderness of sorts, is the Ghoul (Walton Goggins). Formerly a pre-war cowboy movie star named Cooper Howard who outright refused to play anything less than a true-blue good guy on screen, he ultimately made many small compromises that paved his way to this Hell. He has since wandered the post-nukescape for over 200 years, looking like the Red Skull as Clint Eastwood, with a conspicuously digitally erased nose. He’s not the only Ghoul out there, but most of them deteriorate into full zombies after a while. Only one with his mad gunslinger skills can consistently obtain enough of the inhaler medication he needs to keep the condition at bay.

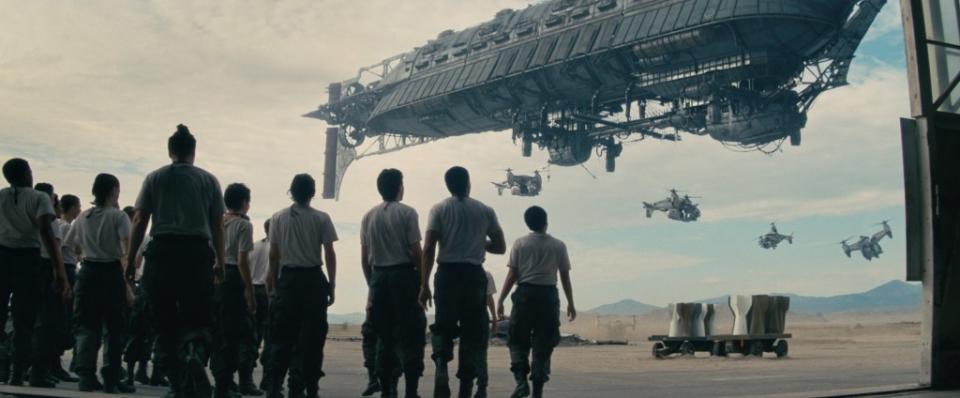

There’s a third lead caught somewhere in the moral middle, with the absurdly portentous name of Maximus (Aaron Moten). He’s part of a military-ish operation called the Brotherhood, which somehow has its hands on massive, fully operational airships, helicopters, and the game’s trademark mech suits. Saved by the group as a child from a literal “nuke the fridge” moment, Maximus feels like he owes them everything, but as a newcomer, he still gets treated like crap, especially when pressed into service as a Squire. Essentially, he’s the caddy for a mech-armored Knight, carrying an oversized duffle bag and performing all the menial and life-threatening tasks. If he sounds a bit like a potential Finn to Lucy’s noble Rey, that’s because he is, except this time in the hands of creators who are fine with depicting interracial romance.

Go West…

About them: considering that Fallout is the work of Westworld’s Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy, you could be forgiven for fearing an overly confusing, twisty narrative. Indeed, the first episode presents the storylines of Lucy, Maximus, and Cooper as if they were entirely unrelated movies spliced together, with completely different styles in different worlds. That doesn’t last long – the three encounter one another relatively soon thereafter, and though the narrative remains divided between different characters in different places, it’s rarely unclear, even when it goes into flashback.

More Shock, Less Awe

In the days of Tales From the Crypt and Dream On, HBO cultivated the “We’re premium cable! Let us shock you!” vibe, which is still there to a point, but their hard-R prestige shows these days – think The Last of Us and House of the Dragon – take their material and atmosphere uber-seriously. Prime Video is clearly looking to recapture some of that old shock spirit, following in the footsteps of The Boys; Nolan and Joy understand the tonal difference and the assignment. Fallout may ultimately have a Christian sort of morality at its heart, but few conservative Christians will ever know, thanks to a somewhat gratuitous parade of jokes about incest, penis-wiping, bestiality, “ass-jerky,” and tossing puppies in furnaces.

Most of these bits feel about as necessary to the script as a 12-year-old yelling f-words to make themselves seem grown-up, but in the right context can be genuinely funny. Like when one character revealing his backstory notes: “I grew up on a fly farm. I was a shitter!” If you’re gonna do toilet humor, let it propel the story forward.

In case it isn’t already abundantly clear, don’t go into Fallout looking for a realistic depiction of a nuked world. It’s primarily satirical and acutely aware of every major apocalypse movie that has come before, loaded with cinematic references that are subtle enough not to browbeat audiences. It’s also not a direct adaptation of any one game in particular. The malfunctioning water chip that’s key to the first game comes up once and is never mentioned again, while the overall plot is most similar to the third game. Like the Resident Evil movies, it’s ostensibly in the world and canon of the games but following completely new characters.

Adapt or Die?

Gamers will have a leg up on twists like the true nature of the Vaults, but attempts to swerve the plot in live-action video game adaptations are overrated. The most popular movie and TV versions of games are usually the ones that stick closest to the original story (The Last of Us, The Super Mario Bros. Movie, Mortal Kombat), twists or no. Fallout splits the difference, with familiar terrain and tropes but different leads.

One thing it does not do is skimp. Whatever the (massive) budget was on this thing, it’s all onscreen. The plot may contrive for us to rarely get more than one of the mech suits on camera at a time, but the sets mostly look practical and huge. Back in 1994, the filmmakers behind Double Dragon hoped to give us Planet of the Apes/Statue of Liberty vibes by showcasing an underwater Hollywood and Vine, and, well, they didn’t. Fallout similarly fails to evoke much emotion with the same (kayfabe) location in a similar condition, but at least it includes a giant mutant axolotl that has human fingers protruding from the roof of its mouth.

This is a show that can do that kind of thing one moment, layer in biblical imagery the next (Lucy is effectively both John the Baptist and Salome in one episode), and conclude with a savage (literally and figuratively) assessment of societal tribalism.

Atom-punk

Fallout is set in a modern version of a 1960s post-apocalypse vision – think Ib Melchior’s The Time Travelers or Beneath the Planet of the Apes. In this fictional-ish America, the aesthetic of the ’50s never changed right up until nukes went off in 2077. (Interestingly, and usefully for the current audience, while it seems that institutional racism/sexism/queerphobia disappeared, McCarthy-esque Red-baiting remained.) It’s not really the ’50s being critiqued, however, though some will miss the message amidst near-constant carnage.

You probably didn’t expect to hear something like The Zone of Interest invoked, but it comes to mind anyway watching Fallout. Both depict the desire to get along and live comfortably while tuning out the horrors just over the next wall, and both ultimately lead the audience to conclude that isn’t, or at least shouldn’t be, possible. Unlike its in-universe Vault-Tec aesthetic, the show isn’t square enough to suggest that being good and doing the right thing saves the day every time. But it does bravely suggest that it’s a reward unto itself and might occasionally change hearts, even when it’s very, very, very hard. It takes a few episodes before the themes start to come into focus, but they all drop at once, so have at ’em.

So, Is It the Bomb?

Fallout is an appropriately named show for many reasons, not the least of which is its effect upon the viewer. It’s a take-no-prisoners explosion right out the gate, but the real effectiveness only sets in once it’s had a chance to linger. The apocalypse in a fresh new coat of paint is the sizzle; the social satire, compromised as it may be, is the ass-jerky that nourishes your attention thereafter.

Grade: 4/5

Fallout debuts on Prime Video on April 10 at 6 p.m. PT.