A coach's mentorship prepares young baseball players for life, with or without the game

Karen knew Jeremiah as a nice little boy, if very shy, who spent recesses watching the other boys and girls play in the schoolyard. He carried the challenges of Down syndrome and autism as gently as he could. He was quite likable.

She taught his elementary special education class. Every day around noon she’d smile and wave him into the sound of shoes clomping and voices singing and laughing, toward his classmates freed into the sunshine. Every day he would silently refuse.

One day, she brought her son to school with her. His name is Tyler. A sophomore in high school, he was gifted academically and athletically. He met Jeremiah. He liked Jeremiah. Everyone did.

Late the next morning, a knock on the classroom door turned the students’ heads. Karen was surprised to see Tyler. The school was near downtown Los Angeles, across the city from where they lived. He’d awakened after his mother had left for school. So he’d charted the city bus route, sorted out the transfers, and come back for Jeremiah.

Together, they ran the playground. They climbed a ladder and whooshed down the slide. Jeremiah cupped one hand, touched it with the fingertips of his other hand and pointed at the slide. Again, he was asking. Again. Again. Again. Jeremiah mounted a tricycle. Tyler pushed him around the yard. Jeremiah had himself a day. A day and a friend.

Karen said, “He became a normal little boy.”

Two years later, Tyler is a senior in high school. He’ll graduate with a grade-point average well above four. In the fall he will enroll at Cal, which he chose over UCLA and Penn State. A left-handed pitcher, he hopes to play baseball there, as well, but the coronavirus has tentacles that took away his senior season after five at-bats and 4 ⅔ innings, that took away his graduation ceremony and prom, that threatens to have him begin college not in a lecture hall but behind a computer. So baseball might have to wait. Or, it might look different than how he’d planned it to. This he knows. He will make do.

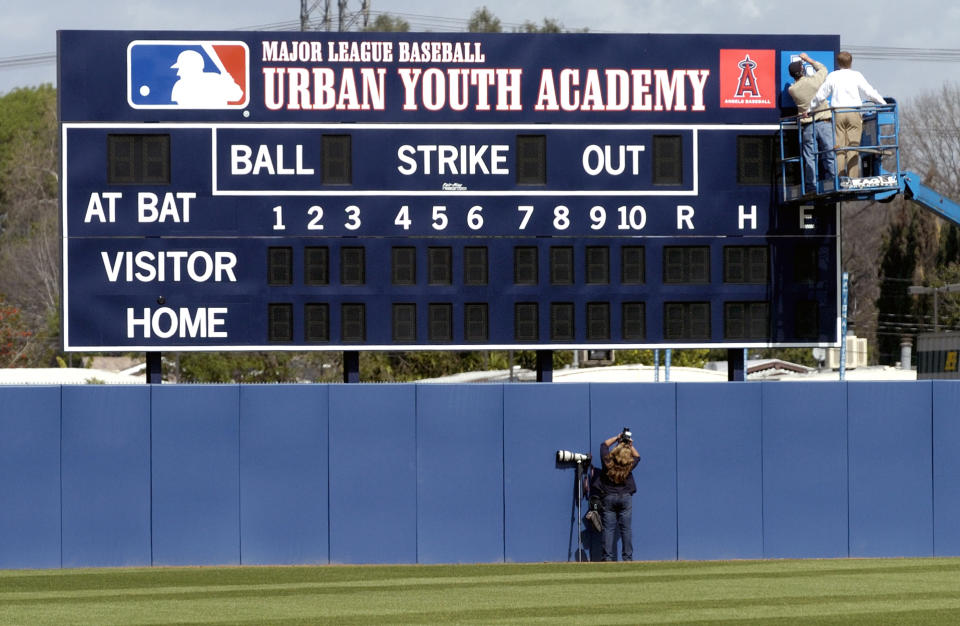

See, this was all covered on a sheet of paper he received some eight years ago, the first day Tyler Mahomes walked into Major League Baseball’s Urban Youth Academy in Compton, handed to him by a tall, confident, educated man named Coach Rocky. “MOTTOS,” by Rocky E. Gholson, advised Tyler — and anyone else who came through the door — in 10 ways how to become a kinder person, a stronger leader and an attentive student. There was no mention of baseball, no mention of a boy named Jeremiah, only of the habits that would make baseball better, that would make Jeremiah matter.

What we can ask is for our children to grow up compassionate. Generous. Selfless. Fulfilled. Happy as a result.

Tyler memorized those mottos within a few days and recited them back to Coach Rocky. Tyler put the mottos on his refrigerator, where they remain today. When Karen and Tyler moved, and the refrigerator with them, so too did Coach Rocky’s mottos.

Together, they ask him to “dream big” and honor “today” and “speak positively.” They scold, “Don’t make excuses.” They say, “I know I can.” They don’t tell him how to throw a 95-mph fastball or hit one, but Coach Rocky’s mottos do seek to put life on a tee. The rest is reps. The rest is timing. The rest is showing up, no matter how many bus transfers.

Tyler, the son of Pat Mahomes and Karen Kramer, who never married, the half-brother of Kansas City Chiefs star Patrick Mahomes, walked onto the Compton campus of the Urban Youth Academy when he was 10. His mom drove him. It’s almost always been just the two of them. Tyler played a lot of baseball on those fields. He did a lot of homework between those games. He taught a lot of the younger boys and girls how to sound out the hard words and how a sentence worked and how square roots weren’t so scary. Tyler’s mom is a teacher. He followed her lead. His mentor is Rocky. Rocky calls him “T-Money.”

“A big brother,” Tyler said. “A father figure for me. Rocky puts kids in a position to do well.”

He hasn’t had less than an A on a report card since his freshman year. He works two jobs. He volunteers to help less fortunate children. He excels in sports. He’s going to Cal. He’s the kid who took two or three or four — whatever it was — buses to spend an hour with a boy for the sake of a smile.

An awful lot of that is mom. An awful lot of that is Tyler. When that wasn’t enough, Karen said, “Rocky tries to be what they don’t have.”

In a place where the heartbeat is baseball, where the language is baseball, where the dress code is baseball, Rocky Gholson is the education development coordinator. Among a thousand duties, he runs the book club. He organizes the SAT prep. He takes the message of the academy into the neighborhoods. He monitors the study sessions and names the academic excellence teams and scours the scholarship applications and asks for more. He learns the faces and then the names and then what they don’t have.

Sometimes what they don’t have is someone who knows their faces and names.

The academy, on the campus of Compton City College, has been closed because of the virus for more than a month. That, of course, means no baseball. It also means a community of boys and girls are at home, riding out a school year and a baseball season from a distance, some in danger of losing ground gained where Rocky set the rules and wrote the mottos.

This is where the real baseball is played and then, in some ways, turned into real lives. The shiny game whose absence is mourned nationally, where there is another looming fight over who gets what money, that doesn’t look much like the sandlot games that are also gone. So there is no fantasy baseball to play, nothing to watch on television, nothing to fill the hours at night, no one to root for and against, only dark stadiums, and that’s a small enough part of it to be insignificant.

MLB sponsors 11 urban academies in 11 cities serving some 65,000 boys and girls. Most of the academies have a Rocky, the guy at the front door giving out free gloves and caps and goals. When baseball restarts, it’ll be in cul-de-sacs, on unmown fields, behind chain-link fences scaled in a single breath. Maybe it’ll be over near the corner of East Artesia and Alameda in Compton, where the boys and girls arrive in school clothes and with backpacks of books and go home in dusty uniforms with their homework done.

“I truly feel bad for my seniors,” he said. “Their senior year is gone. They don’t get to finish it. It’s a problem.”

He is in Virginia. When the virus spilled across the country, he was in the air, on his way to tend to his ailing mother. Joan Gholson is 80. She taught second grade for 45 years. She and her husband, James, raised their children in Queens, New York, then in Dinwiddie, Virginia. Rocky attended Howard University, where he played four years of basketball and graduated with a degree in Public Relations Communications with a minor in child psychology. James died 17 years ago.

In the moment Rocky had grown fearful of losing touch with the two dozen or so boys and girls in his core academy program, he was at the bedside of the woman he called, “The teacher of the century.”

“She is the teacher every kid craved,” he said. “She was like all of their mothers. She loved them. They loved her back. When I was 12 or 13, I went to her school to help. I fell in love with children, the way they were sponges for information and love.”

When his own wife died of cancer, when he had a daughter to finish raising on his own, he’d become credentialed as a teacher. Soon, he discovered the academy, moved into a house in the neighborhood and became part of the place, like they’d built him into the foundation.

When he’d mentioned the children he’d left back in L.A., his mom had told him, “Call them. They need you.”

So, twice a week, he does. Every one of them, including Tyler. He sees there are hundreds of thousands, maybe millions, of kids out there just like his. Just like the little shortstop who needs a raised eyebrow once in a while. Like the little outfielder who needs an attagirl. Like the little pitcher who needs extra time in math, but slays it in history. They all get a special handshake. They all get a story. They all get a chance to laugh and belong.

“The real deal,” he said, “is I’m there to help them on life skills. They don’t even know. I’m just using education as the bait. The ultimate goal is life. A safe place to turn to. For them to know somebody cares for them.”

So he calls. He asks how things are going. He asks them about school, about keeping up. He asks if they’re ready. The required answer is yes.

Rocky asks them to spell five words. Then he asks them to answer five math problems. He waits. Then he orders them to go find a newspaper or a magazine. When they return to the phone, he says, “Read to me.”

“A lot of them are extremely bored being at home, a little antsy,” he said. “I used to tell them to be prepared, that one day they’ll no longer be going to school and they’d miss it. Well, here it is.”

So, he makes a cup of coffee for his mother every morning and she asks about his kids and he tells her about the little shortstop and the little outfielder and the little pitcher. He worries. He also is where he wants to be. Where he needs to be.

With the teacher, the best he ever had.

“This,” he said, “has been the best month of the last 20 years for me.”

When Tyler was maybe 12 years old, Rocky invited him to a fancy celebrity golf tournament held to benefit the Compton academy. Frank Robinson hosted. Tyler memorized a speech he was to give to those who were there. He was so nervous.

He stopped midway. He started over. Afterward, he apologized to Rocky.

“I messed up,” he told Rocky.

Rocky smiled at him.

“T-Money,” he said, “it’s OK if you mess up. What matters is you were here. You tried. You were great.”

More, they’d had themselves a day. There’d be so many more of them they could hardly keep count.

On one of those days, they’d look up and find there was no baseball. None at all. Maybe, just maybe, it would dawn on them — all that baseball over all those years against all those hardships, that was just getting them ready for when there’d be none.

More from Yahoo Sports:

generic

generic