Largest Space Images Ever: Euclid's Views of Galaxy Clusters, Galaxies, and Nebulae

In July 2023, scientists launched the Euclid Space Telescope into orbit with a straightforward, albeit massive, task: to map the dark universe, revealing the dark matter and dark energy that we cannot directly observe but makes up the bulk of everything.

Now, scientists affiliated with the mission have published a huge amount of data that will inform how the team proceeds in attempting to directly detect dark energy—the mysterious stuff that apparently drives the universe’s accelerating expansion. (It’s not to be confused with dark matter, which makes up about 27% of the cosmos.)

Euclid’s first test images were published last August, but its first five scientific images were released in November. Those shots—capturing a few galaxy clusters, several galaxies, and an iconic nebula—are spellbindingly beautiful, in addition to containing useful data about dark energy and dark matter.

The new images are at least four times sharper than those taken with ground-based telescopes, according to a U.K. Space Agency release, and the latest image drop includes the largest images taken of space from space. The following images are early results from the telescope and make up just 24 hours of Euclid observations. In other words, it’s just a teaser for what scientists hope will be a prodigious portfolio of scientific data.

Euclid’s visible imager (VIS) boasts a staggering 600 million pixels, while the infrared sensors on the telescope’s Near Infrared Spectrometer and Photometer (NISP) add another 66 million pixels. Without needing to cut through Earth’s variable atmosphere to image the heavens—after all, it’s in them—Euclid is capable of taking particularly crisp images of structures deep in space.

“To achieve its core aim of better understanding dark energy and dark matter, Euclid’s measurements need to be exquisitely precise,” said Mark Cropper, an astrophysicist at University College London and who led the development of VIS’ optical camera, in the same release. “This requires a camera that is incredibly stable, incredibly well understood, with conditions inside it needing to be controlled very carefully.”

The VIS camera we developed will not only contribute beautiful images, but help us answer fundamental questions about the role of dark energy and dark matter in the evolution of the Universe,” Cropper added.

You can read all of the scientific papers associated with Euclid’s Early Release Observations here, on Euclid’s website (fair warning: there are a handful of them).

Without further ado, check out Euclid’s newest images in the following slides.

The Dorado Group

A young group of galaxies known as the Dorado Group is seen merging with one another. The Dorado Group is 62 million light-years away and is sandwiched between larger and smaller galaxy clusters, making it an intriguing study subject for understanding galactic evolution and how these massive structures interact.

A Close-Up of Galaxies in the Dorado Group

Here, we see an edge-on view of one of the galaxies in the Dorado Group, with more galaxies in the background. In the previous image, this galaxy is in the top-left of the image, showing the impressive resolution of Euclid’s imaging.

Galaxy Cluster Abell 2764

This region of space contains hundreds of galaxies in a halo of dark matter. Dark matter is literally invisible—it is not directly detectable by scientific instruments—but astronomers know it’s there because of its gravitational effects on things we can see. The bright star towards the bottom of the image is V*BP-Phoenicis, which is in the Milky Way. Euclid mitigates the scattering of light from the foreground star, so that the brilliant, distant background—around 1 billion light-years from Earth—is visible.

Spiral Galaxy NGC 6744

This is a classic spiral galaxy, so named for its swirling arms. Its exact name is NGC 6744 and it lies about 30 million light-years from Earth. The arms are made up of dust, which is associated with gas in the galaxy fueling the formation of new stars.

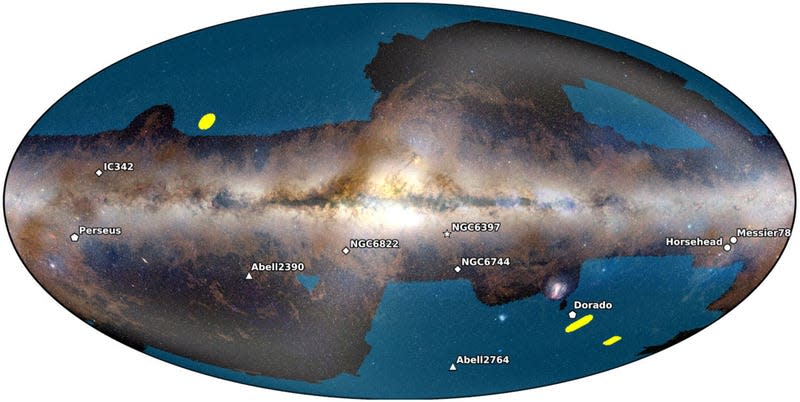

Where Euclid’s Images Are in the Sky

We are taking a quick break from the Euclid images to show you where each object is in the sky. The disk seen here is, perhaps obviously, our Milky Way galaxy. The galaxy clusters, stellar nurseries, and nebulae Euclid has so far seen are distributed across the universe.

Galaxy Cluster Abell 2390

Another galaxy cluster imaged by Euclid’s recent campaign is Abell 2390, which is a significant 2.7 billion light-years from Earth. If you look closely at the cluster of bright objects near the center of the image, you’ll see intracluster light—light from stars separated from their galaxies and spread across intergalactic space. Euclid can use this intracluster light to see regions that contain concentrations of dark matter. Euclid can take perceptive, wide field images like this one much faster than other telescopes.

Gravitational Lensing in Abell 2390

One way that astronomers can “see” dark matter is through gravitational lensing, a quirk of spacetime by which light is bent by the gravitational fields of massive objects. Here—in a close-up of the concentration of light from the previous image—you can see gravitational lensing occurring in the arc of a distant galaxy. Light that otherwise would appear as a straight line takes on an arc shape, as it is bent around massive objects. Though dark matter cannot be directly observed, gravitational lensing can hint at where dark matter resides, manipulating ordinary matter through its gravity.

The Stellar Nursery Messier 78

A gossamer of interstellar dust called Messier 78, as seen by Euclid. Messier 78 is the bright magenta region near the center of the image, in which stars are born. According to an ESA release, this is the first time scientists have been able to detect objects smaller than stars (namely, filaments of gas and dust) in Messier 78. In taking this image, Euclid discovered over 300,000 new objects—showcasing just how much of the heavens will soon be revealed.