Forget teaching to the test for STAAR. Now Texas students are writing to bots | Grumet

Many people helped my daughter grow as a writer: My husband and I nurtured her reading and took her on adventures. A decade’s worth of teachers coached her on writing and challenged her thinking. Countless authors showed her how to put emotion and experience into words.

But now that it’s time for the state of Texas to assess my 16-year-old’s academic skills, a computer program will decide whether her writing is good enough.

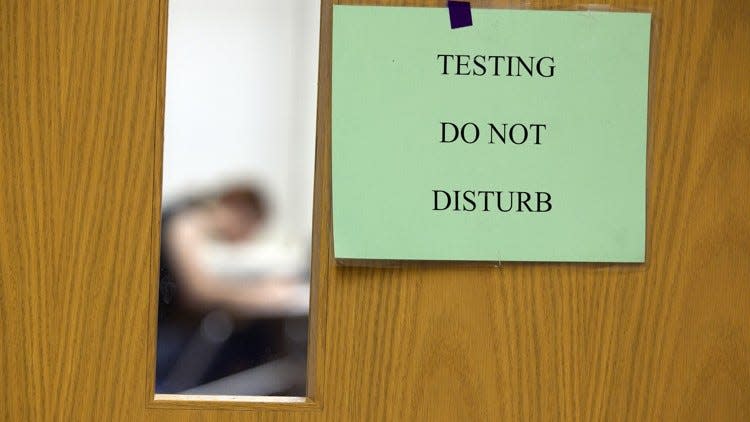

We are in the thick of a STAAR testing season with a sci-fi twist: This year, the free-form responses in the State of Texas Assessment of Academic Readiness exams will be graded by new “automated scoring engines” designed to “read” what students write.

This includes the short written responses in the science and social studies STAAR tests, as well as the short-answer and longer written components of the English reading/language arts exams. All told, students’ typed responses in about 5.4 million STAAR tests this year will be graded with this technology, reducing the need for human scorers from 6,000 last year to about 2,000 this year.

And while students and teachers are understandably anxious about the reliability of this tech — “How smart is this computer?” my skeptical teenager asked — I’m concerned about what writing will become when students are focused on getting a passing grade from a computerized bot.

The competence of this technology has been the most immediate question, given the high stakes of the STAAR. Students must pass some of these tests to advance a grade or graduate from high school, and all of the exams are used to judge schools and districts.

The Texas Education Agency emphasizes that humans are involved in every step of developing and checking the performance of the automated scoring engines. Each computerized tool is designed to grade a specific question and then tested extensively against how humans graded responses to that same question, said Chris Rozunick, TEA director of assessment development.

These tools are not artificial intelligence, she added. They do not learn and adapt as they consume more information.

Put another way: If ChatGPT is “a nice, souped-up Ferrari,” Rozunick told me, the STAAR automated scoring engines are more like a go-kart.

Much simpler and less likely to veer off-course.

The TEA expects about 25% of the computer-graded responses to also be reviewed by humans. Some will be spot-checks to ensure the computer grading matches what a person would give. In other cases, the computer will flag tests for which it has “low confidence” about the accuracy of the score because the student’s response doesn’t resemble what the bot expected to see. A human scorer will take a closer look.

“We're not going to be penalizing those kids who come in with very different answers,” Rozunick said. “As a matter of fact, we love seeing (the computer flag those responses) because that's a good indication that the system is working.”

My worry is what happens much farther upstream.

Concerned about the computer’s ability to “read” student responses, some teachers this year are urging kids to keep their sentences short, their message basic. And while that is sensible advice for engaging with this technology, the very premise of writing to a bot compounds the problem of formulaic prose long fostered by standardized tests.

When space is limited and testing stakes are high, students lean on writing rules. They don’t want to get dinged. Some will write in a rigid fashion that becomes their go-to approach even outside the STAAR because either they think all writing is supposed to be that way or they haven’t had enough opportunities outside the test-prep world to develop their voice.

“We used to hear testimony in legislative hearings about how colleges from other states could instantly recognize students from Texas who were applying because of the formulaic way they wrote, and that was directly tied to the testing system,” Holly Eaton, director of professional development and advocacy for the Texas Classroom Teachers Association, told me.

And while Texas has been trying to unwind that problem, the move to computerized grading of written responses threatens to snap us back.

When the news first broke about Texas using computerized tools to grade STAAR writing responses, state Rep. Erin Zwiener, D-Driftwood, lamented on social media: “I taught writing in college. One of the first things college writing instructors have to do is *unteach* the stilted standardized test writing.”

“A machine cannot recognize good writing,” she added. “A machine can only recognize writing that follows a formula.”

Sadly, a part of me recognizes that talking to computers is becoming a necessary skill. Chatbots provide the first tier of customer service for many companies, and in many cases, job hunters’ résumés will be scanned and sorted by technology before an applicant reaches a human. Interacting with this tech is part of our lives.

But there is a much richer world of thought and expression beyond that. Texas needs to cultivate the thinkers and communicators for that world — people who can analyze problems, articulate solutions and empathize with others.

No matter how accurate the “automated scoring engines” are for the STAAR, we are still left with test questions and student responses designed for computer consumption. It's an exercise in processing data instead of developing writers. Texas will not be better for it.

Grumet is the Statesman’s Metro columnist. Her column, ATX in Context, contains her opinions. Share yours via email at bgrumet@statesman.com or on X at @bgrumet. Find her previous work at statesman.com/opinion/columns.

If you have questions about the answers

Once a STAAR test has been graded, parents can visit texasassessment.gov to see their child's overall score. They can also see their child's responses to all of the questions on the test and how those responses were scored. Parents can raise any concerns with their child's school. If school officials agree there is a problem, the school district's testing coordinator can ask state officials to take a second look.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: In this year's STAAR, Texas students' writing is graded by computers