‘Facebook has nuked our page’: Inside Kansas Reflector’s clash with the social media Goliath

On Thursday, Kansas Reflector saw all its Facebook posts deleted. The platform also blocked users from sharing links to the site. The disruption grew to include two other sites on Friday. (Photo by Sherman Smith/Kansas Reflector)

On Thursday morning, my phone began to flicker with notification after notification from Kansas Reflector readers. Something was going on with our Facebook page, they wrote. They couldn’t see posts anymore. They couldn’t share links anymore. Links they once shared had been removed.

Many of them voiced concerns that Facebook was taking down our content for a specific, political reason. They mentioned the raid on the Marion County Record newspaper, while others pointed to our stories about Emporia State University, former Topeka city manager Stephen Wade and ongoing legislative hijinks.

We scurried into action, trying to both figure out what was going on and reassure our 13,000 followers on the platform.

“It looks as though Facebook has nuked our page,” I messaged my bosses and tech support.

Four days later, our posts have been restored, Meta spokesman Andy Stone has apologized and we’ve made the national news again. CNN.com wrote a story about the fracas, which saw two other websites temporarily blocked. PC Mag, the Wrap and Editor & Publisher ran with the story. The Kansas City Star and Wichita Eagle editorial pages weighed in, and “Handmaid’s Tale” author Margaret Atwood lent her support.

All’s well that ends well, right?

Not exactly.

I don’t believe that our coverage of the Marion County raid or Kansas Legislature led to the digital purge of Kansas Reflector content. But I can’t say that for certain, because Facebook has been maddeningly opaque about the entire situation. Stone outright denied that the likeliest target — a column from documentary filmmaker Dave Kendall criticizing the platform — was the culprit.

But his technical explanation, given in a Friday afternoon phone call with editor in chief Sherman Smith, left us scratching our heads.

“It had nothing to do with the content. It had nothing to do with the story that you guys wrote,” Stone said. He instead blamed a domain issue with three separate websites, all of which operate separately and just happened to have posted Kendall’s column.

“It was a security issue related to the Kansas Reflector domain, along with the News From The States domain and The Handbasket domain,” he added. “It was not this particular story. It was at the domain level.”

Conversations with States Newsroom technical support staff raised questions, to put it mildly, about Stone’s explanation. However, he did not explain further during the interview with Smith, or when apologizing online. During a crisis like this (and Meta PR should have seen it as a crisis, given its impact on the company’s reputation), he should have instead been transparent about what went wrong, explain how engineers fixed the problem and assure journalists that they will not be targeted in the future.

Instead, he refused to say whether other news outlets should be concerned about what they post.

Anyone involved this past week now understands that putting our civic conversation into the hands of a single for-profit business generates profound risks for society as a whole — risks that few recognized or understood until the company ensnared 3 billion people.

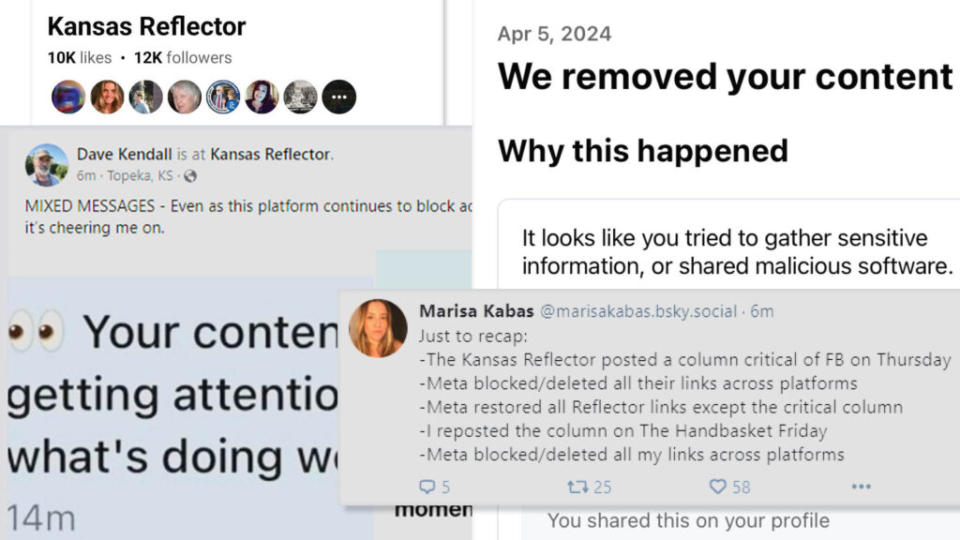

Social media posts reflect Facebook’s actions to block news sites that published Dave Kendall’s column, which was critical of Facebook. (Illustration by Sherman Smith/Kansas Reflector)

What went down

Here’s a full account of what happened throughout Thursday and Friday, reconstructed from our accounts, and what we heard from our readers and Facebook.

Shortly after 8 a.m. Thursday, we attempted to post a link to Kendall’s column. We do this every morning at roughly the same time for our daily opinion piece. We had no reason to expect that the platform would behave differently on Thursday than any other day.

But the link wouldn’t post. The site spit it back at least twice, and we eventually simply posted a link to our home page, telling readers they could find Kendall’s work there.

Within a half-hour of that post, every single Kansas Reflector article shared on Facebook over the past four years — 6,000 stories, columns and briefs — was deleted by the platform. All of the writing that folks had done in sharing or commenting on those links also was deleted. No new posts could be shared from our website.

Anyone who had ever shared our articles received messages telling them our website was in some way a cybersecurity risk. This was not true.

Kansas Reflector and States Newsroom, reached out to Meta in every way we knew how, all the while responding to dozens upon dozens of messages from confused and concerned readers. We posted a short column to our website and Facebook page (as text only) explaining the situation to the best of our ability. To put a fine point on it: We were being asked to explain the actions of a multibillion dollar company with California headquarters.

Finally, about seven hours after the content vanished, much of it was restored. Stone, the Meta spokesman, posted a comment to X, denying that the blocking of links and removal of posts had anything to do with Kendall‘s column. He apologized for the error and said it had “since been reversed.”

We hoped at that point that the situation was complete.

Late on Thursday and into Friday, however, it became clear that the situation was far from finished. The platform still wouldn’t allow links to Kendall’s column, and readers told us some Kansas Reflector links hadn’t been restored. We submitted several reports on the matter from our account but never heard back.

On Friday, we decided to experiment. We would post links to Facebook for the column, but not the version on our site. We instead tried to link to the column as it appeared on News from the States, the States Newsroom site aggregating content from all 50 state-level newsrooms. Independent journalist Marisa Kabas had republished Kendall’s column to her website, The Handbasket, and we tried sharing that link as well.

Facebook rejected our attempts to link to the column on either site. Then, at about 12:30 pm. Friday, Facebook nuked both News from the States and The Handbasket.

All posts linking to both of those sites were removed from Facebook, and users were blocked from sharing any new links. So much for a single error having been reversed. At that point, the conversation shifted from our readers and supporters to journalists on X.

Kabas shared the news with justified incredulity. Legal reporter Chris Geidner wrote that “truly wild” stuff was going on, but not using the word “stuff.”

Roughly three hours later, Meta finally backed down. Posts from both Kabas’ and States Newsroom’s sites were restored. And users could finally share Kendall’s column on the platform. At this point, Stone called Smith to offer his take on the entire situation. You will have noticed some of his quotes in the first section of this column.

Stone told us that Facebook would not inform readers that it had misled them.

“You guys will cover it,” he told Smith.

Our editor updated his second-day story about the situation, and we all went back to covering news from the Kansas Statehouse. But continued messages from readers via Facebook and through email make it clear that many are still upset and confused by the situation.

As I work on this column Sunday, I am still responding to readers and reassuring them that we have not been hacked and are not sharing malicious software.

The company behind Facebook, Meta, also owns and operates Threads, Instagram and Facebook Messenger. (Photo by Alexander Koerner/Getty Images)

Searching for explanations

Let’s talk specifics for a moment.

The takedown of Kansas Reflector articles on Meta platforms was more extensive than many grasped at the time. We wrote and talked about Facebook, because our readers did. National outlets covering the situation also focused on that platform.

But we should note that all Kansas Reflector content was taken down and blocked on Threads as well. That’s the Twitter competitor Meta rolled out last year. Also, we were prevented from posting on Instagram because we included a link to this website in our bio. Finally, we couldn’t even send Kansas Reflector links to those who reached out to us via Facebook messenger.

Given that all of these are separate products, I would expect that whatever happened in the bowels of Meta was on an extremely fundamental level. In other words, the story is not that Facebook blocked us, it is that Meta blocked us from all of their best-known platforms.

We do know a couple of things for sure.

One is that Meta and its platforms have increasingly distanced themselves from news and political content in recent years.

We also know that has translated into Facebook directing less traffic to the pages and content shared by news organizations and advocacy groups.

Both right- and left-leaning groups have complained of Facebook making their material more difficult to find. Readers who replied to Kansas Reflector posts on the situation told us of multiple instances in which they believed their politically themed posts had been removed for one reason or another.

The facts point in a single direction: Facebook would rather users enjoy fluffy, lighthearted memes than engage with the serious and sometimes troubling issues of the present day. Given the flak Facebook received in the 2016 election and the Cambridge Analytica scandal, this makes sense from a corporate perspective.

But it’s not good for civic conversation.

Meta’s recent decisions have made its platform less useful for journalists and those interested in keeping up with the news. (Photo by Sherman Smith/Kansas Reflector)

Distinctions and caveats

I should add some important distinctions and caveats in talking about this story. One of them is that Kansas Reflector doesn’t depend on Facebook for much at this point. This has led to a situation in which the social media site now generates somewhere between 2-3% of our total website traffic. This mirrors the experience of other news sites during the same time.

In other words, if the block had continued after Thursday, it wouldn’t have changed much about what we do or how we do it.

We care about what the site did because of how it affected our readers and followers on the platform. We also care because Facebook told those readers untrue things about us. I wish that Stone had paid more attention to this particular aspect of the story. We take our users’ online safety, privacy and security seriously. So does our parent organization.

We also care because the block and its aftershocks caused profound disruption to Kansas Reflector, distracting us from the vital work of covering the end of the state legislative session. Big decisions were being made about state taxes and spending. Both Smith and myself found ourselves instead wrangling with a social media company. What’s more, Meta’s action created an immediate chilling effect for local news organizations posting their content to the platform.

“We won’t be sharing this editorial on our own Facebook page,” wrote the Kansas City Star editorial board. “Just to be safe.”

Don’t get me wrong. Meta may have the right to shut down or limit access to websites, as long as it complies with the law. As a corporation, its commercial speech enjoys First Amendment rights. However, wholly excluding links of a public service, nonprofit news website would certainly appear to contradict the platform’s self-professed interest in being a site catering to the broadest possible public.

Just because you have the right to do something doesn’t make it a smart decision.

These past few days require careful consideration from readers, journalists and Meta itself. There is a difference between making content more or less visible based on algorithms and blocking it altogether. There is a difference between sharing links to misinformation meant to undermine civic norms and sharing links to fact-based reporting and commentary. There is also a difference between issuing glib apologies and actually taking responsibility for harm.

This experience suggests that Facebook no longer cares to make such distinctions, no matter your ideology.

That certainly makes it less useful for folks interested in finding out what’s going on in Kansas politics and for those covering it.

Kansas Reflector, like the Alaska Beacon, is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Kansas Reflector maintains editorial independence.

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX

The post ‘Facebook has nuked our page’: Inside Kansas Reflector’s clash with the social media Goliath appeared first on Alaska Beacon.