TBT: The Secret History of Hawaiian Prints

For the past few years, tropical prints have re-emerged as a major trend on the streets and the runways. But what you may not know is that there was a time when Hawaiian prints were designed in Hawaii, but made on the U.S. mainland — until one man brought them home to Hawaii, creating a clothing manufacturing and retail empire, and making the tropical print a truly elegant statement. His name was Alfred Shaheen.

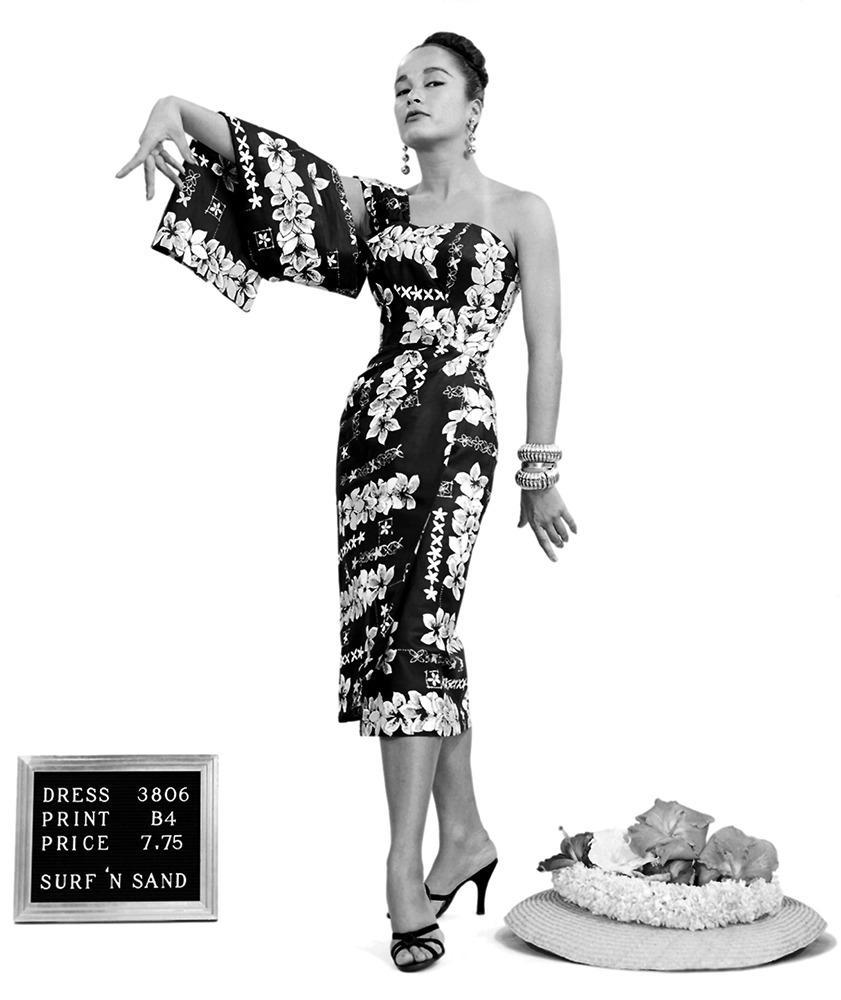

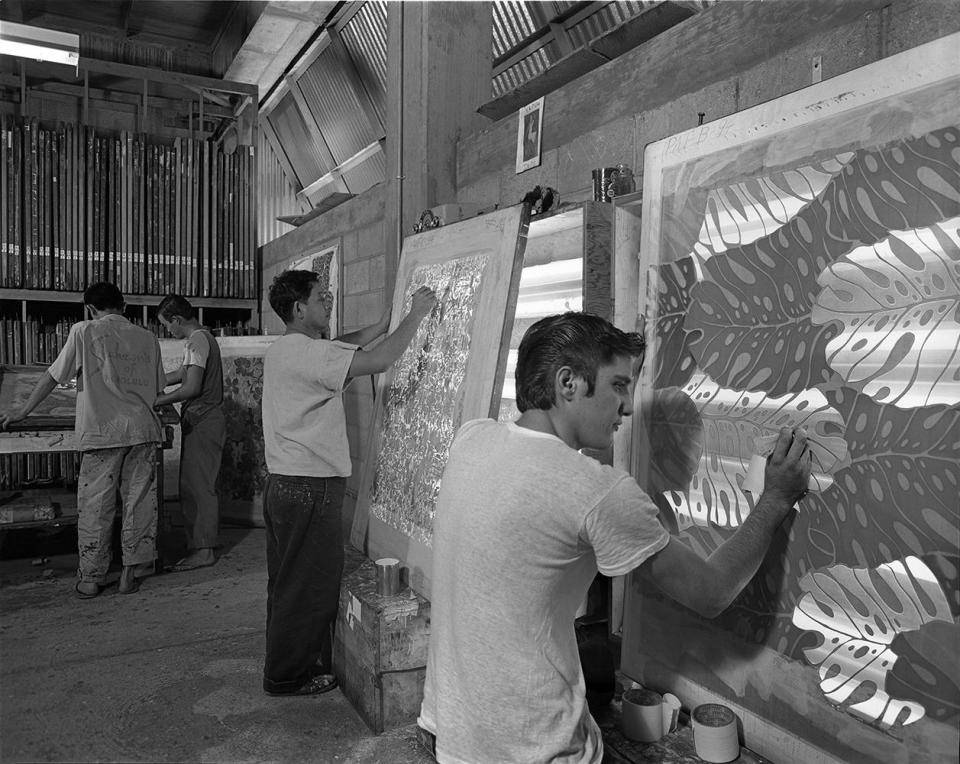

Shaheen’s parents moved from Lebanon to New Jersey, where they established a silk manufacturing business using techniques from their home country. The family later moved to Hawaii in the 1930s. After serving as a fighter pilot in World War II, Alfred Shaheen moved back to Hawaii to join his family’s garment business, eventually branching out to establish his own. He broke away from the then-common custom of importing Hawaiian-print fabrics from the mainland (which often resulted in 10-month wait times), instead engineering his own equipment to manufacture the garments. He and his parents trained other Hawaiian locals to design innovative patterns for the garments, silkscreen fabric (using a process Alfred had developed), and sew the garments. Shaheen’s company also created the first woven metallic fabrics, that were beach-friendly and machine washable. By 1956, Shaheen had built his own factory to create the garments, plus a series of showrooms and “Shaheen’s of Honolulu” retail stores employing over 400 people. By the time Hawaii became America’s 50th State in 1959, Shaheen’s was making 4 million dollars annually, through a robust retail, licensing, and wholesale business — that’s about 32.5 million today.

Shaheen employed genius marketing techniques that would later become ubiquitous, too, such as the first “pop-up” shop in department stores worldwide. Wholesalers could purchase flat-packed walls, racks, and hangers to create an immersive environment Shaheen called “East meets West,” bringing people who might never visit the island a taste of Hawaiian style.

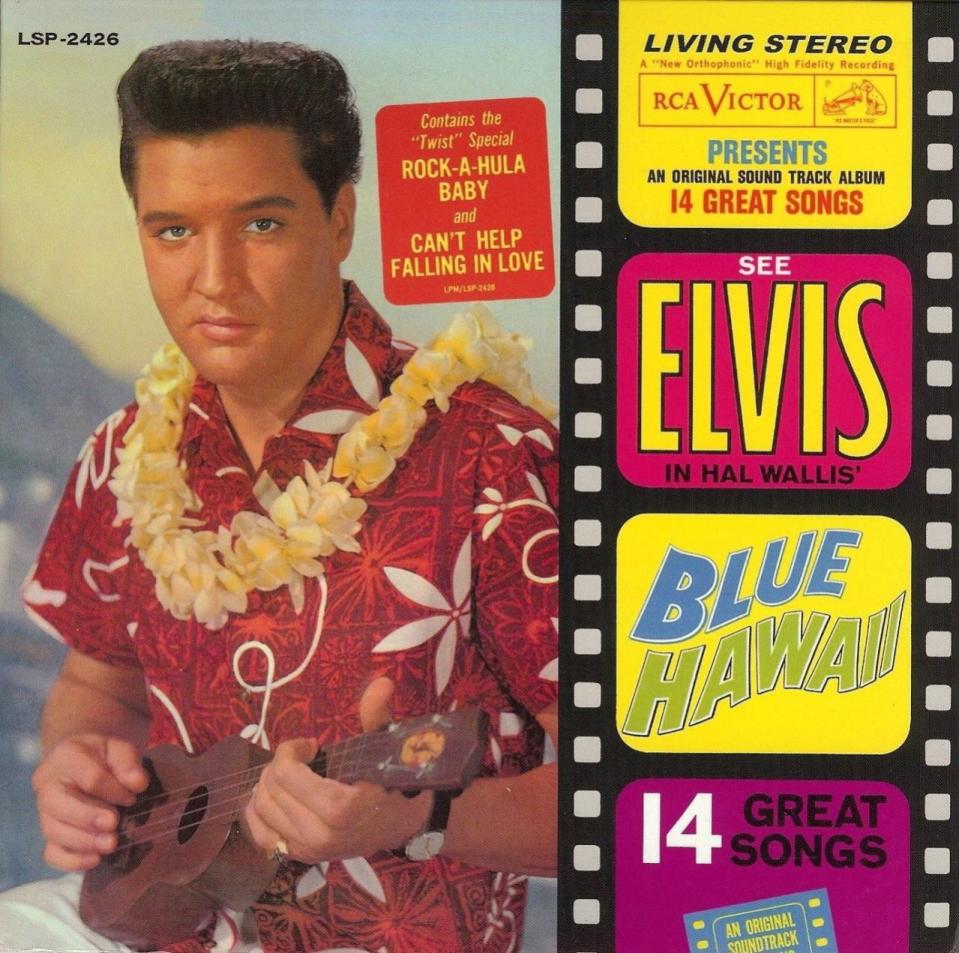

Shaheen also brought about innovations in the prints themselves. These days, the “tiki” Hawaiian aesthetic is considered “kitsch,” but those prints have their origins in the traditions of Shaheen’s multi-cultural staff. Hawaii was then home to many first-generation immigrants from Asia and the South Pacific. Shaheen would send his staff on inspiration trips to countries around the world, taking in museums, libraries, and nature, to encourage them to understand and celebrate the local flora and fauna, which were then incorporated into prints. Japanese lanterns, Chinese incense sticks, and lotus patterns inspired by Indian temple walls all feature in Shaheen’s prints, making them unique among other designers’ traditional patterns. Even the Tiare flower so commonly associated with the Hawaiian print (and featured on the Elvis Presley’s famous “Blue Hawaii” shirt on the film’s poster), was actually from a trip the Shaheen design team took to Tahiti.

In 1988, Alfred retired, as Hawaiian prints became an ironic throwback — think Chunk in The Goonies, or Weird Al Yankovic. In the ‘90s, brands like Tommy Bahama made the Hawaiian shirt a staple for middle-aged men who look like Sammy Hagar and listen to Jimmy Buffet — a far cry from the beautifully crafted, stylish garments Shaheen had made.

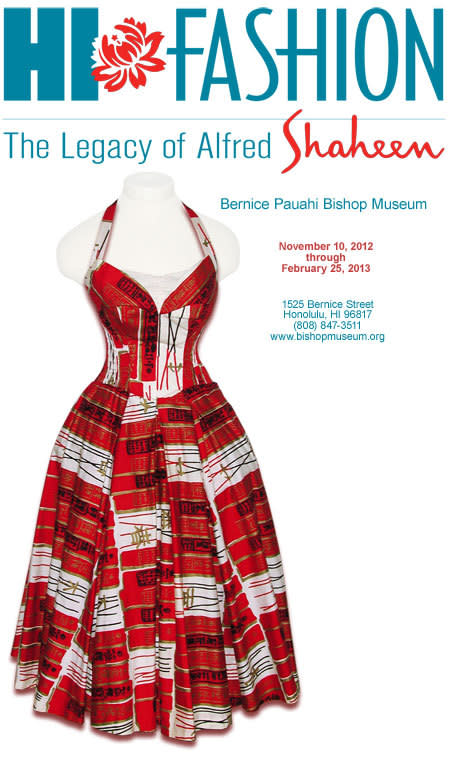

An authentic Shaheen print represents so much more than the casual holiday garment. Shaheen created a garment industry in Hawaii when there was none. Throughout the trend’s apex in the ‘50s and ‘60s, his savvy production innovations and vertically integrated business model made him the largest manufacturer of “aloha wear” in Hawaii, and his pieces are still considered collectible, timeless, and iconic. With brands like Prada and Proenza Schouler, and people like Pharrell Williams taking inspiration from Shaheen’s version of the prints, we’re finally seeing a beautiful resurgence and appreciation for this true fashion original.

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, and Pinterest for nonstop inspiration delivered fresh to your feed, every day.