I Hated My Mother's Cheap Clothes, But I Was Wrong

There comes a day when you have to open your mother's closet, tear her coats off the hooks, snatch her dresses off the hangers, remove her shoes from their shelves, push her carefully folded underwear into a pile and shove all of that into large garbage bags.

When that day came for me, I was overwhelmed by pain, rage, and guilt. I found it sickening that my mother's clothes were there, all neat and intact, when my mother was dead. And I couldn't help but see what I was doing as a violent betrayal, a desecration-almost a crime. I had to do it, though, because it was my duty and there was nobody else to perform that task. And so I went at it, stumbling over my mother's shoes, groping for drawer handles through my tears. Dropping items, picking them up, dropping them again.

I found it sickening that my mother's clothes were there, all neat and intact, when my mother was dead.

The last time I was inside my mother's closet, I was ten or eleven years old. We lived in Moscow then, and every time my mother would leave me in the apartment alone, I would sneak into her room, open her enormous old wardrobe and explore her clothes.

What a thrill it was! The suits hung on the left side, the dresses on the right. The shelves housed sweaters and hats; the drawers were full of scarves and underwear. I hated the underwear drawer-all those huge bras, garter belts, and rolled-up stockings. But I loved the top shelf, where my mother kept her three fur hats: an ugly yellowed one, one made of mink, and a gray one. I would climb onto a chair and stroke the gray one, chanting: "You're my kitty. Here, kitty kitty."

Next, I would examine the dresses. Woolen, cotton, silk. Knitted, tailored, drapey. Dark, light, flowery. Dresses were for going to the theater, for dancing, for chatting and laughing-but mainly for making all those strange men stare at my mother. My father had died when I was two, and whenever my mother and I went for a walk, a man would follow us and try to chat my mother up. I was terrified of their attention, but also secretly proud. I would slip one of her dresses on and turn back and forth in front of the mirror, saying: "No, absolutely not!" just like she did.

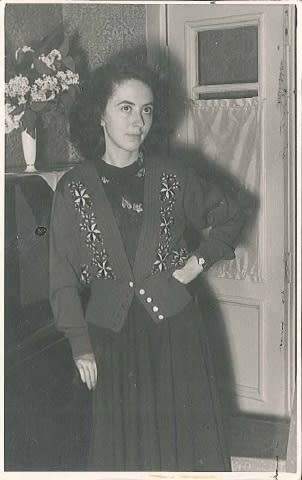

But my favorites were the jackets my mother wore to work. She taught at a university, and took me to work with her a couple of times. I watched her enter the lecture hall, greet hundreds of intimidated students, and ascend to the lectern, as powerful as a human being could possibly be.

I would wear one of those jackets and try to summon the power that had to come with them. My favorite was her felt vest: beige, with brown embroidery along the hem and appliqué of brown leather. It reached my knees, stiff and heavy like armor. But I didn't think it made me look ridiculous; I imagined that it made me look strong and grown up. I would sit my dolls in a row and try to intimidate them with my stare.

Now, here it was, hanging in the back of the closet. Ragged, scratchy to the touch, with its stupid leather leaves and that heady old smell, looking pathetic. When we immigrated to the U.S. in 1994, my mother had brought the vest with her, but never wore it again. I took it off the hanger, about to shove it into a garbage bag-then put it aside. I simply couldn't throw it out.

My mother's American clothes were a different story. It seemed that she had left her sense of style in Russia and couldn't be bothered to develop a new one. When we moved to America, my mother was only 57, but the only job she could find was tutoring neighborhood kids in math. She said she didn't need to wear her power clothes any longer, and the mere sight of them reminded her of what she had lost.

For the last few years of her life she did her clothes shopping exclusively in Staten Island's LotLess, which was the only store accessible by foot. I would offer to drive her to the mall or buy something for her, but she always refused. She wore shapeless jeans over stretched-out yoga pants, men's shirts over sweaters, and two berets sewn together to make sure that the entire surface of her head was covered.

I took this for a sign of weakness, or giving up, and it made me angry.

It was only as I stood in the middle of her now shockingly empty closet that it occurred to me how wrong I was to despise my mother's LotLess clothes. They were actually an expression of her defiance and independence. LotLess was the store she could go to by herself; these were the clothes she could afford on her own, and she would wear those clothes in a way that she found comfortable. If she wanted to sew two berets together, so be it. She didn't give a damn what anybody thought of her appearance.

I kneeled down and started clawing through the garbage bags like a raccoon. I recovered a few of those LotLess sweaters, a couple of T-shirts, and that double beret. I took one look at it, and I started to laugh, for the first time in days. The bottom part was stretched out so it would cover my mother's ears, and the top was sewn over slightly askew so it would look like a classic playful beret. It was the craziest contraption, but it did have my mother's feisty spirit.

I keep the beret in my closet now, on a special shelf, along with the felt vest. As for the LotLess shirts, my daughter wears them to class. She thinks they are pretty cool.

You Might Also Like