Counterfeit Fashion Drives Big Profits On Internet Black Markets

By Scott Christian and Jacob Steinblatt

Soon after opening his dressmaking firm in Paris in 1858, Charles Frederick Worth began sewing labels into all of his couture pieces, essentially creating the world’s first designer label. What quickly followed was a demand for that label, and others like it, by many who could not afford it. To fill that demand, an alternative rose up that today costs the fashion industry $28 billion annually: counterfeit goods.

By the early 20th century, millions of fake couture garments were sold throughout the U.S. and Europe, prompting a variety reactions from within fashion the industry. Coco Chanel declared that, “Being copied is the ransom of success,” while couturier Madeleine Vionnet tried to dissuade counterfeiters by implementing difficult-to-copy techniques in her designs and marking her labels with a thumbprint. Jeanne Paquin was the first couturier to battle counterfeiting through the French courts.

Read more: Step Inside The Open Casting Call For Kanye’s Yeezy Fashion Show

Today the knockoff market as a whole brings in $600 million annually and represents 5 to 7 percent of global trade—twice the annual profits from the illegal global drug trade. In terms of counterfeit fashion, style-centric Europe has been hit especially hard. According to a recent EU study, close to 10 percent of all fashion related products sold—shoes, clothes, and accessories—are counterfeit, resulting in the loss of anywhere between 363,000 and 520,000 jobs throughout the Europe. Italy in particular has had it trough, losing around $4.9 billion and 50,000 jobs annually.

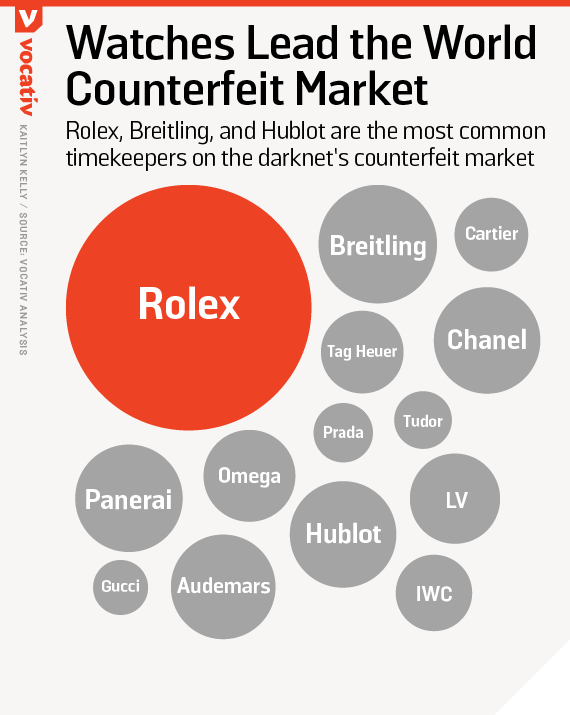

Though phony leather goods, particularly handbags and footwear, cost European artisans hundreds of thousand jobs a year and get most of the attention in intellectual property court, they are not the most frequently counterfeited goods in the world. That distinction goes instead to wristwatches, something Vocativ discovered after collecting thousands of dark net market postings from four separate, illegal markets and more than 20 vendors in dozens of countries.

Perhaps most predictably, Rolex is the most counterfeited timekeeper in the world, but smaller brands like Breitling, Hublot, and even Italy’s Panerai are also popular among those making, selling, and buying imitation watches, Vocativ discovered.

Watches, which are small and easy to ship, are the perfect product for dark net markets and indeed recent growth in the phony luxury good market can be attributed to the rise of online vendors.

“The Internet has completely changed the whole counterfeit industry,” says Ariele Elia, Assistant Curator of Costume and Textiles at The Museum at F.I.T., and co-curator of a 2014 exhibition on fashion counterfeiting called Faking It. “In the ‘80s, it was Canal Street in New York and Santee Alley in L.A. But everything is online now.” According to the World Trademark Review, online counterfeit retail sales have grown at an annual rate of 20 percent or more since the rise of e-commerce, and the volume of knockoff goods sold online will soon surpass those sold by physical vendors.

“It’s difficult to track down who these online counterfeiters are,” says Elia. “You can shut down one website and 50 others pop up.” But ubiquity isn’t the only problem when it comes to the online counterfeit marketplace. In some cases, sites are so good at masking themselves that consumers aren’t even aware they’re buying fakes. “It used to be that people who bought fakes knew what they were doing,” says Susan Scafidi, Academic Director of the Fashion Law Institute at Fordham University. “But now, with the rise of e-commerce, and with the secondary marketplaces, it’s getting hard to tell.”

In Europe, this can prove especially problematic since it’s not only against the law to sell counterfeit fashion, it’s also illegal to buy it. In the U.S., the Trademark Counterfeit Act of 1984 made it illegal to sell, but not illegal to buy counterfeit fashion. And while that does protect the few people who buy forged fashion accidentally, it can stymie law enforcement thanks to a more limited set of policing options. “We certainly don’t want to criminalize people who accidentally buy fake fashion,” says Scafidi. “But we do in some way need to address the demand side.”

One way that fashion houses are addressing the demand is by recreating their work at a lower price point and selling it at fast fashion chains. H&M, for instance, has been incredibly successful in their collaborations with luxury brands like Balmain and Alexander Wang. But, as Scafidi points out, to really change things, it’s going to have to take shift in the mindset of consumers. “Unfortunately for fashion houses,” says Scafidi, “I think that mindset is shifting in the wrong direction.”

Scafidi singles out social media as being partly to blame for this. “Who cares if it’s beautifully made by hand from the finest materials if on Instagram it looks exactly the same as the cheap knockoff?” she says. The consumer today wants variety because it makes for better Instagram posts, and quality is less important when the goal is a good photo. “Current social trends are pushing consumers away from value and quality,” says Scafidi.

Read more: Social Media Might Kill Fashion Week As We Know It

Although it may exacerbate the issue, the rise of social media didn’t create the culture that powers counterfeit fashion. Here in the U.S., that culture stems largely from the early 20th century tradition of department stores illegally copying couture. “A lot of people like to argue that American fashion was built off copying the French,” says Ariele Elia. By the 1950s, couturiers began licensing their designs to department stores in order to produce legal copies, but the idea that you could buy cheaper copies of expensive couture had by then taken hold in the minds of the American public.

And while it’s the demand side that most agree is the key to ending counterfeit fashion, it’s the supply side that has garnered the most attention. Specifically the supply side provided by China, the world’s largest producer of counterfeit goods. According to a report released by the UN in 2013, nearly 70 percent of all counterfeit goods seized globally between 2008 and 2010 came from China. And U.S. Customs officials say that figure is likely closer to 87 percent. Vocativ’s own deep web analysis supported these numbers, finding that China produced 40 times more fake designer products than Afghanistan, it’s next closest competitor.

Part of this comes down to the fact that China is the world’s leading exporter, with 70 percent of those exports being manufactured goods. But another part of the problem is cultural. As Dana Thomas writes in her book Deluxe: How Luxury Lost its Luster, “China doesn’t have a history of intellectual property ownership.” It’s only been since the economic reforms of 1978 that “the government has slowly embraced the notion of intellectual property ownership.” Elia agrees: “They don’t really see it as copying or counterfeiting, they see it more as surviving and building their economy.”

For brands, this creates a double-edged sword. By manufacturing in China, they are able to cut cost. But such cost-cutting measures can backfire when factories hired to produce the authentic pieces end up also covertly producing the fakes. “Designers shouldn’t be surprised that their pieces are knocked off because, if they are manufacturing in China, they’re selling their designs to the biggest counterfeiter in the world,” says Elia.

And while knockoff fashion may not be going anywhere anytime soon, Scafidi says there is reason to be optimistic. “It’s not as out in the open as it used to be, and that’s a sign of progress.” She points out that online marketplaces like eBay are doing more to partner with brands to flag items that are probably counterfeit.

“In the end it’s an arms race,” she says. “It’s a problem that will be with us for a long time, but it’s a problem the industry can’t stop addressing lest they lose the value of their business entirely.”

*Vocativ is the official content partner of New York Fashion Week. Follow us on Facebook & Twitter for all our latest coverage.