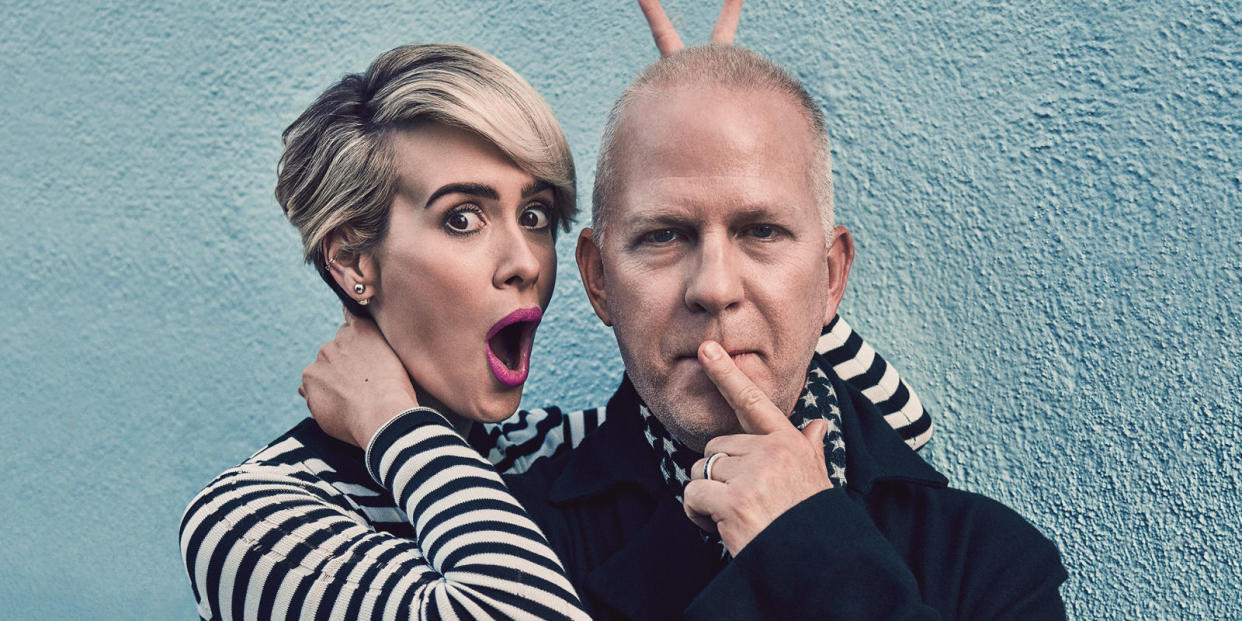

The Beautiful, Dark, Not-So-Twisted, Love Between Sarah Paulson and Ryan Murphy

This article originally appeared in the February 2017 issue of ELLE.

Sitting alone in my idling rental car on the Fox Studios lot in Los Angeles, I observe a woman in a black-and-white houndstooth skirt and top-the sort of wasp-waisted getup a female character might have worn in a Douglas Sirk film-emerge from a chauffeured black sedan and briskly click her way toward me in high, high heels. I am 15 minutes early, an eternity in Hollywood, and as I sit there gathering my belongings and thoughts, I am not expecting her to come up to my car, peer in the driver's-side window, and say, with crisp, disarming matter-of-factness: "Are you doing this?" Meaning, of course, our interview.

The woman is Sarah Paulson, in whose film and television work I've been steeping for weeks, yet I had momentarily not recognized her. Possibly because her manner is so straightforward and unvarnished, more like a no-nonsense female surgeon than a Hollywood actress-you'd expect the latter to float past you and into the building, avoiding you until the appointed time. Or maybe because she'd just come from a press conference and was thoroughly done up, in orange-red lipstick and vintage Valentino, as though from another era. "I didn't want you to think I'd overdressed. I mean, I'd dress for you, but not like this," she joked as we walked up a short flight of stairs. Or maybe because she'd recently chopped her streaky blond bob into a gamine pixie cut to play Audrey, the actressy actress in Roanoke, this season's American Horror Story.

Her manner is so straightforward and unvarnished, more like a no-nonsense female surgeon than a Hollywood actress.

Mostly, though, I'm convinced I didn't recognize her because, in spite of her distinctive features-those sculptural cheekbones and that full, ripe-fruit mouth-Paulson is the kind of performer who disappears completely into whatever character she's playing. You never glimpse the actress slipping out from behind the fiction; the convergence is always total, seamless, complete. On some level, I suppose I thought I'd be interviewing Lana Winters, the canny, muckraking lesbian journalist from American Horror Story: Asylum; or Hypodermic Sally, the reckless, amoral ghost-junkie from AHS: Hotel; or perhaps especially Marcia Clark, the earnest, infamous, real-life prosecutor from American Crime Story: The People v. O.J. Simpson.

Paulson, who is 42, has been acting professionally for more than two decades, ever since graduating from Manhattan's Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts (aka the Fame school) in 1993. She has memorably inhabited roles such as Nicolle Wallace, senior adviser to the McCain campaign and frustrated tutor to Sarah Palin, in HBO's 2012 film Game Change; and Harriet Hayes, the devout Christian comedian on NBC's short-lived 2006 series Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip. But it is her recent work with TV impresario Ryan Murphy that has brought her the most acclaim, including five Emmy nominations in six seasons on American Horror Story and an Outstanding Lead Actress win for American Crime Story's Marcia Clark, all on FX.

Paulson talks at a quick clip, often gesturing with her hands-she turns her palms up in front of her, like she's holding a bowl-to underscore a point. She unequivocally credits Murphy with her current success. "By continuing to employ me and continuing to throw enormous acting challenges at me, he has made me find my confidence, and I did not have that before him," she says, with touching earnestness, as we settle into a sofa in Murphy's loftlike offices to wait for him. To the left of us hangs a black-and-white portrait of a young Faye Dunaway. To the right, a black-and-white portrait of '60s-era Warren Beatty. As we talk, they look over us, silent and eerie, like the patron saints of bygone Hollywood.

Later that afternoon, Murphy arrives. He is waist-deep in directing his latest show, Feud, an anthology series about famous squabbles, and he'd hosted a Democratic fundraising event (President Obama attended) at his Beverly Hills home two days earlier. Paulson and I follow him down a hall to a conference room decorated with tasteful, muted midcentury-modern furniture. Paulson points to a tan leather chaise longue. "What's this for?" she says. "A Freudian session every time someone has a breakdown?"

"It's my fainting couch," Murphy dryly replies. Having spent the better part of a month watching American Horror Story through the cracks in my fingers, I genuinely believe he might need one. Murphy is a deft conjurer of atmosphere and mood-whether that's the spooky Victorian-style Briarcliff asylum with its grisly medical torture chamber, or the Art Deco Hotel Cortez with its bloody glam-rock decadence-and ever since I began watching AHS, my life has felt haunted. Curtains blowing in the breeze of an open window start to freak me out. And when Laurie London's cheerful rendition of "He's Got the Whole World in His Hands" comes on the radio during my 4 a.m. drive to the airport, I am certain it's foreshadowing my imminent demise, as happy '50s music always does. It's surreal to be sitting with the mind behind the horror, watching him do something so mundanely human as eat a cookie.

"What are you eating?" Paulson demands. "Is that an Oreo?"

"It's a delicious lard Oreo," Murphy deadpans, since we are in fat-free, gluten-free, dairy-free Hollywood. Murphy, 51, has a cool, detached air about him. He does not fill silences to make you feel at ease. But he is also wryly funny, with a drollness glinting from behind his serious facade. I'm reminded of the peculiar, delightfully capricious tone of American Horror Story, which has the same dark hilarity roiling just beneath the surface, always threatening to erupt.

Ryan Murphy, for the four people who haven't seen one of his wildly popular shows, is a witty provocateur with a penchant for camp, a pusher of boundaries whose taste is sometimes called into question. He's as transgressive, as distinctive, and as vital a voice as exists on television today, and he's also something of a social crusader. He and his creative partner, Brad Falchuk, were the arch masterminds behind FX's sharp and often graphic plastic-surgery satire Nip/Tuck, which brilliantly skewered American vanity and our cavalier attitude toward carving ourselves up. They also created Fox's teen musical Glee, the a cappella–style after-school–special series that toppled age-old high school hierarchies, making theater nerds cool and bullying forever unfunny. The show dealt with a host of incendiary issues, from homophobia to teen pregnancy to eating disorders, reminding viewers that teens, at life's most fragile inflection point, are grappling with heavy shit, too. And though it irked many critics, who found it increasingly preachy and maudlin, always sounding its moral principles with church-bell clarity, it was beloved by fans.

Murphy's next series, the genuinely frightening American Horror Story, was a direct response to the cheerful, earnest rectitude of Glee. As Murphy once said, "I was like, 'I can't write any more nice speeches for these Glee kids about love and tolerance and togetherness. I'll kill myself.… I'm going to write a show about anal sex and mass murders.' " American Horror Story, an anthology series whose plotlines change but whose tone is as consistently sinister and morally murky as Glee's was lighthearted and morally unambivalent, just completed its sixth season. It's a clever mash-up of genres (horror, fantasy, Gothic melodrama, slasher) that wields its black humor like a sharpened knife. Along similar lines, there's Fox's Scream Queens, another dark comedy, this time about a group of sorority sisters being stalked by a killer. Murphy has called it "bubblegum splashed with blood."

If there's a unifying theme to all of Murphy's projects, it's that he places the outsider at center stage, introducing mainstream America to characters they don't often encounter on television, and maybe not in their daily lives: gay and transgender characters, older women, women of color, disabled characters, those with Down syndrome, interracial couples-all of whom appear on Murphy's shows.

On AHS: Freak Show, perhaps the starkest example of this principle in his oeuvre, viewers follow the behind-the-scenes goings-on of a 1950s-era circus troupe of differently abled characters as they confront various killers. Murphy received his share of criticism for that season, since professional actors played the main roles (Sarah Paulson was a pair of conjoined twin sisters; Evan Peters, a man with lobster-claw hands; Jessica Lange, an amputee). But he is also rare among directors in casting disabled actors at all, including British performance artist Mat Fraser; Jyoti Amge, the world's smallest woman; the late Ben Woolf, who had pituitary dwarfism; and the late Rose Siggins, who had sacral agenesis. It's also no small thing to show that people with disabilities dance, drink, gossip, work, fuck, and live just like so-called "normal" people, that they are no more "freaky" than anybody else.

If there's a unifying theme to all of Murphy's projects, it's that he places the outsider at center stage.

Murphy does not shy away from exploring the thorny contemporary topics that arise when confronting difference-from sexism to racism to fat shaming to aging to disability-and, at least on American Horror Story, these subjects are not always treated delicately or with reverence. As viewers, we may feel shocked, confused, annoyed, bewildered, scared, unsettled, or flat-out offended, but, as is always the case with Murphy's work, we are guaranteed to feel. We are never bored.

Last year, as an executive producer on the Emmy-winning American Crime Story: The People v. O.J. Simpson, Murphy proved, as he had with the earnest HBO movie The Normal Heart, that he also has another, more traditional mode, one that's neither soapy nor campy. The series, for which Murphy directed four episodes, was a smart, subtle portrayal of the O.J. Simpson trial that slyly shone a light not only on the racism and sexism of the whole spectacle (the detective with the swastika collection, the media's unfairness toward Clark) but of our current cultural moment. Murphy is now prepping for the second and third seasons of American Crime Story, which will look at Hurricane Katrina ("the ultimate American crime, which wouldn't have happened to rich white people," he says) and at Andrew Cunanan's murder of Gianni Versace ("Versace was his fifth victim, and he got away with it basically because of homophobia"). The plan is to do "more social examinations than tabloid examinations," he says, meaning no JonBenét or Menendez brothers.

And then there's the eight-part first season of Feud, set to air on FX in March. Feud will focus on the decades-long rivalry between Joan Crawford and Bette Davis, the pair of aging divas who starred in What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?, the camp classic about a former child star turned fading Hollywood actress who holds her paraplegic sister hostage in an upstairs bedroom. The series stars Jessica Lange as Crawford and Susan Sarandon as Davis, as well as a host of other Hollywood deities: Kathy Bates as Joan Blondell, Judy Davis as Hedda Hopper, Catherine Zeta-Jones as Olivia de Havilland, and Sarah Paulson as Geraldine Page.

Hollywood legends, particularly of the female variety, are Murphy's specialty. "No one loves a lady Oscar winner more than Ryan," Murphy's (female) boss, Dana Walden, chairman and CEO of Fox Television Group, told me. Like the small-screen equivalent of Pedro Almodóvar, another director known for camp, melodrama, operatic gestures, and a love of grand-dame actresses, Murphy has his roster of favorites: Jessica Lange, Kathy Bates, Frances Conroy, Connie Britton, Angela Bassett, Lady Gaga, and Chloë Sevigny have all appeared on multiple seasons of his shows.

But also like Almodóvar, whose best-known muses are arguably Carmen Maura and Penélope Cruz, Murphy has his favorites among favorites. Until the two most recent seasons (Hotel and Roanoke), Lange had a leading role in every reboot of AHS, but there has been only one constant throughout, and that has been Paulson, who has emerged, with American Crime Story, as Murphy's closest collaborator.

"So, hit it," Murphy says, all business, turning to me.

I ask whether Paulson is his muse. He thinks for a minute. He is uncannily still, his legs crossed and his cheek resting lightly in his hand. "He sits there, and he's like a really still ocean," Paulson tells me later. "I wouldn't say 'lake'-it's too small. And it can be unnerving, because he can be inscrutable, and you don't know exactly what he's thinking."

"It's a very lopsided term, muse," he says thoughtfully, after a few beats. "Inspirational for only one person." He holds forth for a bit about the history of famous director-actress pairings, those mysterious, intense relationships that have given birth to so many magnificent films. He points out that many times the relationships were "infused with a kind of caregiver thing, or sexuality." He mentions Bette Davis and William Wyler, who made three films together, most famously Jezebel, for which Davis won the Oscar for Best Actress. "A lot of that work happened off-camera because they were sleeping together, so there was a trust there, and also a fear of being exposed," Murphy says, noting that the male director often treats the female actress "like a doll." He wrinkles his nose. "That's like a weird puppet master thing, like, 'Move your chin and let me fix the bow.' "

By contrast, Murphy and Paulson have "a really modern relationship," he tells me. "It could only have happened in this place and time, with both of us being where we are as adults," he says. "Twenty years ago, would I have been out of the closet? Maybe not. Would Sarah have been forthright about her choices? Probably definitely not."

What he means, I realize, is not only that their relationship is platonic, but that it stems from that adult place most people reach in their late thirties: an I-don't-give-a-fuck honesty about your desires and your choices. Murphy is happily married to the photographer David Miller; they have two boys, ages four and two. For the past couple of years, Paulson has been involved with actress and playwright Holland Taylor, who is 32 years her senior. She is surprisingly forthright about the relationship, but she also refuses to put it in a neat, easily shelved box. "I have been with men, and I have been with women, and I don't make a sort of declaration about what it is or what it means," she later tells me.

Murphy, who started as an entertainment journalist and got his break when he sold a rom-com script to Steven Spielberg, met Paulson more than a decade ago, in 2004. They were both "coming off WB shows," as Murphy puts it. (Popular for him, Jack & Jill for her.) "We had sort of done our juvenilia, and we both had a lot to prove," he remembers. He cast her in an episode of Nip/Tuck as a patient who pretended to have stigmata. Paulson impressed him immediately; she asked a lot of questions and was "very obsessed and worried about everything," Murphy recalls. This might have annoyed some directors, but not him. "Oh, she seems like my cup of tea," he remembers thinking. "Somebody who I feel has an attention to detail, like me."

When he cast Glee, he wanted her for the role that ultimately went to Jayma Mays, but Paulson was on Broadway costarring with Linda Lavin in Collected Stories. "Oh, remember?" Murphy says, with a wink. "And then I kind of got mad."

"He was a little mad at me," Paulson echoes.

"I was like, 'This is going to be a worldwide sensation!' But, to her credit, she was very loyal to her play." He sits back in his chair. "I must have been snippy for, like, six months."

On American Horror Story, Paulson generally provides the intelligence-and the normality, such as it is.

The following year, in 2011, Paulson accompanied Lange, with whom she had costarred in The Glass Menagerie on Broadway, to a benefit where Murphy was also in attendance. According to their joint origin myth, Lange, who was playing Constance Langdon, the swanning, scheming neighbor (a sort of Minnie Castevet character) on AHS: Murder House, turned to Murphy and said, "Can't you find something for Paulson?"

Murphy wrote her a small part as a medium who, with her long coral nails and silk blouses, looked like a Junior League member-and was hungry for her own reality show. "All I had to say was, 'Sarah, the entire performance is based on your manicure.' She knew instantly what I was talking about, and we were off to the races."

Since then, Paulson has appeared in nearly all of Murphy's productions. In American Crime Story, as Marcia Clark, she is the moral heart of the series: a rape survivor whose animating purpose is to defend victims of domestic violence. On American Horror Story, Paulson generally provides the intelligence-and the normality, such as it is. She's the clever journalist who escapes the asylum and the killer, the serious-minded coven headmistress trying to protect her young charges from nefarious forces, the prissy actress who turns out to be an iron-willed survivor.

It's surely not an accident that in every season of AHS, except for a very recent one (no spoilers), Paulson's character remains alive; as other critics have noted, she is a version of what film studies professor Carol J. Clover calls "the Final Girl" in her book Men, Women, and Chain Saws. This resourceful, lone female survivor is a common slasher-flick trope. The Final Girl is the last woman standing, as it were, so the audience is forced to identify with her.

But in Paulson's case, I don't think we identify with her because she survives. Instead, Murphy lets her survive because we identify with her: We trust her, with her clear, rapid-fire way of speaking; her charmingly slight lisp; her dark, penetrating eyes. She seems smart, competent, and, if not always likable-that dreadful word too readily applied to female characters-then real, like someone we might know. She serves as a kind of anchor, tethering the viewer to reality. Thus Murphy can commit all manner of outlandish acts-slicing throats, killing off beloved characters, having them say outrageous and inflammatory things-and we will go there, in part because we trust Paulson implicitly. Murphy has placed his faith in her, and the audience can sense it.

The longer we talk, the clearer it becomes that Murphy trusts Paulson offscreen as well. "I have the dream, and then I let her in on the dream, and then we let other people in on the dream," he says, referring to his creative process, "but she's the one I tell first." Many times, she is the only one he confides in. "I don't even tell my husband. Ever. He'll read it in the trades, and he'll be like, 'What the fuck is this?' " He laughs. "That has been a bone of contention in our house. But it's a very precious thing, and I don't give away my creative vulnerability."

To understand Paulson and Murphy's affinity for edgy material and eagerness to take nervy creative risks, one has only to look to their pasts. Murphy was born and raised in a conservative Catholic household in Indianapolis. "I grew up in a very anesthetized home," he says, "so I was drawn to watching or reading or smelling or having sex-anything that made me feel like, 'Oh, I'm...alive.' " His mother was "a failed actress and a beauty queen" who worked at various retail jobs. His father was the district sales manager for the Indianapolis Star News; he'd wanted to be a lawyer, but was too afraid to take the bar. "I grew up in this house with broken dreams, and I remember thinking, 'You know what? Fuck it. I would rather fail than be miserable,' " he says. "So I have applied that philosophy to my career. I am not going to do anything unless I am afraid of it."

As a child, he spent a lot of time alone, "with no adult supervision-I really did whatever I wanted," he tells me. By the time he was an adolescent, he was "very out of the closet," and for this he was "vilified, but also loved and championed" by his classmates, he recalls, reminding me that Glee was rooted in autobiography and that William McKinley High was based on Murphy's own school. "I loved musicals and I loved Barbra Streisand and I loved Louis Malle," Murphy says, evoking the show's DNA. "My tastes were very bizarre, but the thing they all had in common is that they took me out of my life and made me feel something."

The greatest influence on his life-and on his future cinematic tastes-was his grandmother. She was a character who enjoyed "black-tar coffee," horror flicks, old films: "She was what we would now call a broad, you know?" She forced him to watch Dark Shadows (he "loved feeling scared"), and when relatives would die, she'd bring him to the morgue with her. It doesn't take a psychoanalyst to draw the line from here to American Horror Story. But his grandmother's true legacy may be that she encouraged him to be original, to fantasize and dream big. "I remember her telling me from a very early age that I was different and special-and that this was a good thing, and to always follow my gut," he says.

Paulson, like Murphy, has long been drawn to extravagant emotions. "If I'm not moved from one spot to another, internally, while I'm witnessing it, reading it, consuming it, whatever, I don't know why we're being asked to the party," she says, leaning forward with intensity as she talks.

I ask her if she ever finds herself, you know, terrified by AHS, where she's had to do everything from shoot heroin, to breastfeed a serial killer, to eat a human leg sprinkled with Lawry's Seasoned Salt, among other grotesqueries.

"She loves it," Murphy says, teasing her, having just admitted that even he held a piece of paper over his eyes while watching the Lawry's moment in the editing room.

"I love it more than anything," Paulson says, in all seriousness, lowering her voice to a whisper. "I'm more scared of feeling stuck in something sedentary or boring."

Later, alone with Paulson, I get a better sense of her own dark places. With uncharacteristic vagueness, she speaks of a "fractured family life" that involved "a lot of moving around, a lot of upheaval." When she was five years old, her mother, an aspiring writer, took Paulson and her younger sister from their home in Tampa, Florida, and moved them to New York, leaving Paulson's father, an executive at a door-manufacturing company, behind. Her mother found a tiny apartment in Queens and worked as a waitress at Sardi's while taking writing classes. In the ensuing years, Paulson bumped around from parent to parent, spending a year with her mom, a year with her dad, summers with her grandparents. She also spent a lot of time alone-playing by herself, watching movies, reading voraciously-and she credits those years for her fertile imagination as well as her performer's ability to costume herself in whatever persona a situation calls for. But the chaos of her upbringing also fostered in her a tendency toward perfectionism and a craving for control.

"I think Sarah felt, growing up, that she was a stranger in a strange land," Murphy tells me.

"Like me, I think Sarah felt, growing up, that she was a stranger in a strange land and that she didn't have a lot of support," Murphy tells me later, when I interview him a second time, and I instantly grasp their solitary-creative-kid bond. "So as somebody who loves her, I just want her to know, 'No, I support you in every way.' " I find myself choked up by the fact that he is giving her what he didn't get and surely wants for himself. Murphy tells me he wants to create a home, a family, a kind of old-school acting troupe, for the actors who work with him-he believes that a feeling of safety fosters the most daring performances. "Sarah, Jessica Lange-they can take risks, and they can walk on a tightrope because they know that I will never let them fail."

It was this sort of mutual underlying trust that led to Paulson's career-defining turn as Marcia Clark. "I knew it would be the scariest, most daunting thing she had ever done. And that's one of the reasons I wanted to do it with her," Murphy says. He told his fellow producers that he wouldn't come on board unless Paulson played Clark. They cast her, and Paulson, control-freaky and detail-oriented as ever, began reading, researching, fine-tuning the particulars that would render her portrayal more authentic. Clark had had dance training, so Paulson walked with a slight turnout. Paulson has thicker lips than Clark does, so she thinned hers with makeup. She even wore the same perfume Clark wore. "She is almost what I could call fanatical about everything-about story, about character, about wigs, about moles," says her costar Sterling K. Brown, who played fellow prosecutor Christopher Darden. "She just wanted to get it right. Her level of dedication to her craft, and to that character, was like nothing I'd ever seen."

"Marcia, Marcia, Marcia," the Emmy-winning sixth episode Murphy directed, is the beautiful culmination of their five years of work together; all their shorthand and easy rapport and ballsy willingness to go all out are brought to bear on this character. Paulson plays Clark with furrowed, chain-smoking, righteous intensity, while viewers witness the many indignities she suffered: a style commentator who calls her a "frump incarnate"; a male boss who apologizes for the media's mean-spirited dissection of her appearance and, in the next breath, offers her media consulting; hotshot male defense lawyers with stay-at-home wives who don't understand she can't work late without arranging a babysitter in advance. Any woman who has ever tried to perform at work while also keeping the home front taped together, or who has fielded unwanted remarks about her appearance, will feel a sting of recognition.

But even among this pileup, there's an incident that stands out: the moment when Marcia Clark walks into court with her unflattering new hairdo. Paulson credits Murphy's direction with the poignant end result. As she tells it, she was standing in the vestibule waiting to enter the courtroom when Murphy said, "I just want you to know, I think you think you look really good. I want you to think you look good." This notion hadn't occurred to her, and it made her "walk in with a kind of little swagger," which renders the moment when Judge Ito says, "Welcome, Ms. Clark. I think"-and the gallery behind her snickers-all the more devastating. "I could not tell you where I stopped and she started, and vice versa," Paulson recalls. "I didn't feel like Sarah had been laughed at. I felt like Marcia had been laughed at, and I felt it as a personal humiliation. Ryan said, 'That's the one we're using; your face turned, like, three shades.' "

"She and Ryan together, it's like watching two people dance," says Brad Simpson, an executive producer on American Crime Story. "They really know how to get the best out of each other. They were like Gena Rowlands and John Cassavetes, just working in tandem. To me, that's the best thing that they've done together."

Sarah Paulson's portrayal of Marcia Clark, a radical, revisionist take on a much-maligned figure, is a surpassing example of her empathic ability to channel flawed and difficult characters. It is also one among many illustrations of Murphy's deep understanding of women and their plight. He gets it, I thought, when I watched Lana Winters sneak into the asylum because she has ambitions to be an investigative journalist and has been assigned a lifestyle story on a bakery. He gets it, I thought, as I watched AHS: Coven, a season that essentially functions as a metaphor for the power women lose as they age: Jessica Lange, as supreme witch Fiona Goode, confronts the waning of her beauty, vibrancy, and sexual potency while the young witches unsteadily come into their own.

Murphy has long been interested in women's stories. "I would much rather have watched Jill Clayburgh in An Unmarried Woman than Star Wars. Even though I saw that movie when I was 11, I related emotionally to being left and thrown in a trash can on the side of the road. Her damage, I got it," he deadpans. "I didn't understand Han Solo at all." Later, he tells me, "I've always felt I've related to women deeply because of being gay and feeling like there was always somebody trying to oppress me, to keep me down, to put me in my place."

Now that he is in a position of power, Murphy is trying to right certain real-world inequities, some of which are especially entrenched in Hollywood. Last February, he founded the Half Foundation; its mission is to fill half the director slots on his shows with women, including LGBTQ women and women of color. (To put this in perspective, female directors made up only 17 percent of TV's directorial roles in the 2015–16 season.) Angela Bassett recently directed an episode of AHS: Roanoke, and Paulson will direct episodes of both AHS and ACS next year. Murphy has also set his sights on writing more roles for women over 40. "So many women have confessed to me, in their dark moments over drinks, how difficult it is to be 40 years old and feel you have so much more to give, and yet there's nothing out there for you to play," he tells me. On Murphy's shows, remarkably, the opposite is true: Few of the actresses he regularly works with are under 40. "It's unfortunate that as you're getting better, the work disappears," says Kathy Bates, who has appeared in Coven, Freak Show, Hotel, and Roanoke. "He's given us an opportunity to continue to work and to develop. He's changed my life. I really thought things were over for me."

"I've always felt I've related to women deeply because of being gay and feeling like there was always somebody trying to oppress me."

Feud, where "actresses of a certain age play actresses of a certain age," as Ned Martel, a writer on AHS, puts it, is Murphy's love of older women writ large. "I specifically wrote 10 roles for women over 40," Murphy says, "because I thought, Let's make this show about that. Let's try to do a period piece that addresses the modern issues that women are dealing with, which are ageism, sexism, pay, diversity, the glass ceiling, men pitting women against each other, women not wanting to support each other because they feel there's only room for one woman at a time."

I ask whether he and Paulson view their partnership not just as an originator of entertainments, but as an alliance driven by larger cultural aims. Murphy looks skeptical. "I don't think of it ever," he says.

"The thing he said earlier about truth," Paulson says, "if that's the place where the work is coming from, it may have that effect you're talking about…."

"But if you go in with a premeditated conceit or idea, I think people will smell the bullshit," Murphy adds. "We are really just trying to tell a good story."

He shifts in his chair. His cell phone has started to rumble, and a group of ACS: Katrina writers are bunching up like cattle outside the door. "I feel like, you know what? I don't know why I got this opportunity. I don't know why I was gifted with this person," he says, gesturing toward Paulson, who smiles back at him. "But I know we're on the highway, and we're not getting off until there's a crash."

You Might Also Like