I'm Not Planning to Stop Dressing Like Jenna Lyons Anytime Soon

By Perrie Samotin. Photos: Getty Images.

In 2011, I was covering fashion for a New York City newspaper which tasked me with creating a two-page spread about some of the more exciting shows I'd seen throughout the spring 2012 collections. The usual suspects jumped out—Wang, Herrera, a newly-invigorated Blass—but the final product featured nothing but 950 words about J.Crew, which had just participated in its first-ever Fashion Week.

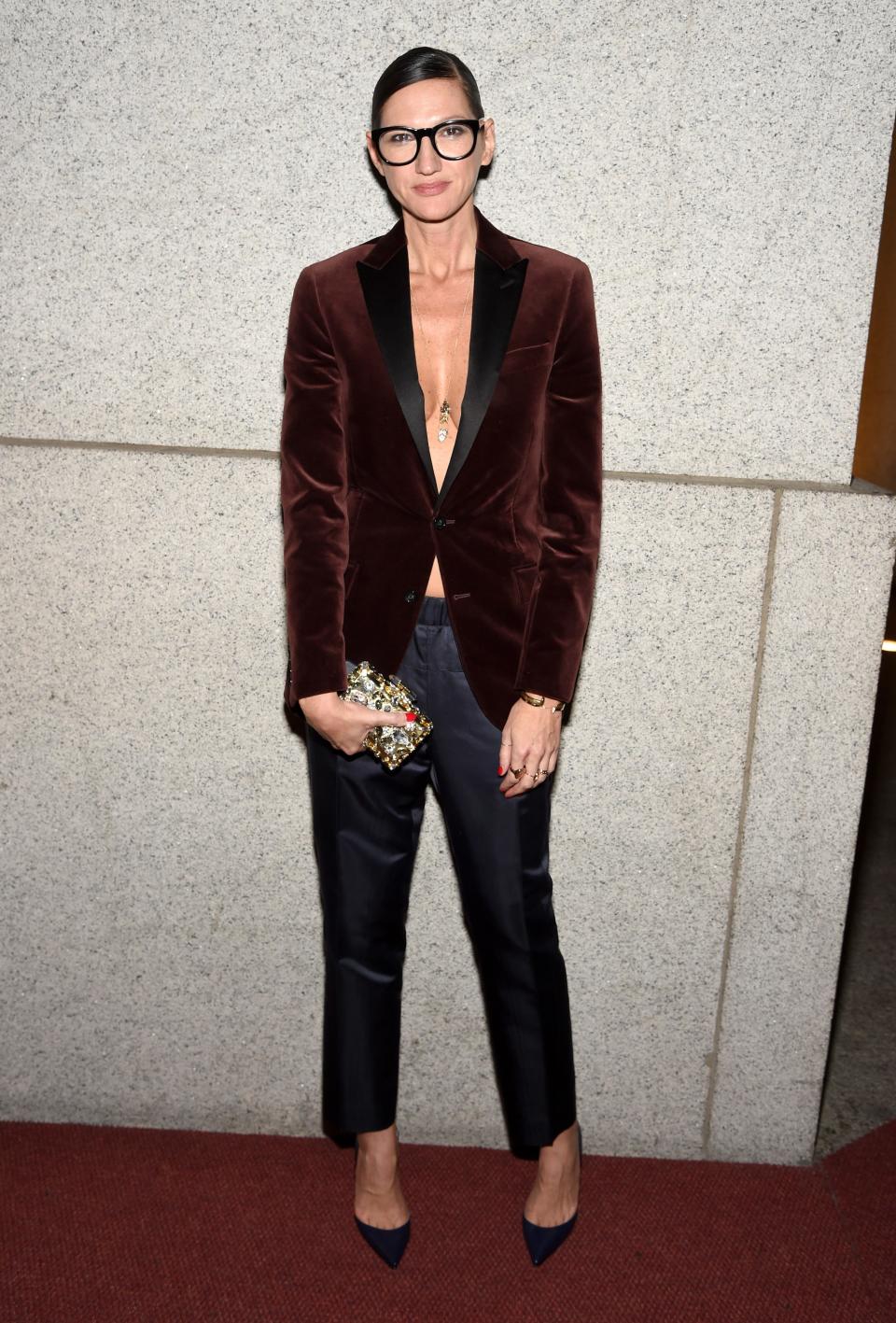

Models wore tangerine trousers with bubblegum-pink blouses, yellow sequined shells with violet pencil skirts, prissy tie-neck tops with denim shorts and overcoats. It was cool, human, friendly, a little nutty—four words I wouldn't equate with the parody-of-itself I'd considered Fashion Week_ to be. The models all wore orange-red lipstick—an early J.Crew signature—and some had thick dork-chic glasses, an obvious nod to the woman behind what I was looking at, Jenna Lyons, whose 26-year tenure with the company escalated from Vice President of Women’s Design to Executive Creative Director. It was announced this week that she'd be exiting.

Lyons—along with CEO Mickey Drexler—overhauled J.Crew's image and inventory, stripping away the brand's woodsy, preppy roll-neck sweaters and chinos, and implementing a new visual mission statement that was more about having fun than always being practical. But instead of relying on twice-yearly presentations in New York to sell the colorful new racks of clothes in its stores, the brand installed Lyons as its face and, in effect, its muse.

It worked: The fashion industry welcomed the revised mall store with open arms—Lyons appeared on magazine covers, in gossip columns, and on the carpet at the Met Gala—and shoppers wanted to be her, or at least look like her. I know I did.

During J.Crew's heyday, I didn't consider the pieces in the store to be particularly enticing. On paper, I gravitated toward the brooding black of Theyskens' Theory and, later, Saint Laurent, but every single time I saw Jenna wearing something—anything—I had an immediate gut reaction, an urge to run out and buy it because of the way she wore it, not necessarily for the piece itself.

For me, it was Lyons who set the bar for "personal style," not the hordes of preening people outside the shows, many dressed like maniacs to capture the camera's lens. Jenna's looks were deliberate, yes, but they didn't feel it.

A master stylist, she paired "fancy” (sequins, satin, tulle, and ball skirts) with utility (chambray, striped tees, oversized parkas, khakis, camo, and cashmere crewnecks), culminating in a quirky, undone, why-didn't-I-think-of-that effect. Pantsuits had an equal feminine-masculine balance, thanks to blouses unbuttoned to the sternum, bra left at home.

YouTube tutorials were created to teach others to mimic the way Jenna cuffed a sleeve or a hem; women everywhere started seeing the cool parallel that comes with wearing glittery costume jewelry with an athletic gray sweatshirt.

I started wearing my old army-green parka out on Saturday night. I showed up in black pants and a sequin top to a good friend's wedding. I discovered that opting for two pieces of outerwear—one fitted and denim, one loose and leopard—made me look like I knew what I was doing in the style department.

I wasn't alone. The Jenna Lyons effect was far-reaching, with women furiously trying to capture her haphazard-but-not-really approach to getting dressed, and the website I was working for at the time regularly used the "outfits to copy" conceit pertaining to her looks during any given month.

A tipping point inevitably followed: In 2013, Drexler publicly agreed with some disgruntled loyalists that the brand's collections had “strayed too far from the classics” and that they were—in all their mixed-print glory—possibly too over-styled, and the retailer later got dragged for its delusional prices, its alienating high-end "collections," its reported lower quality, and its declining sales in a marketplace that includes Zara and H&M.

Still, I think Jenna's impact on the way we'll continue to approach style is evident, even if we're not regularly stopping into our local J.Crew store. It's visible in the kooky glam-granny ethos that pervades current high-fashion collections, including Alessandro Michele's "new" Gucci, in the enduring photos of Michelle, Sasha, and Malia Obama that don't feel dated, in the women I see right here in the Glamour office.

Drexler told Business of Fashion—which first reported the news—that the decision to part ways with Lyons was mutual, and Lyons will be staying on as an advisor until her contract runs out in December. After that, it'll be interesting to see what she does. Her own line seems like the obvious next move, but even if she decides to do nothing related to fashion, I'm glad I have six years of outfits to look back on and, invariably, copy.

This story originally appeared on Glamour.

More from Glamour:

What's That Salad the Kardashians Are Always Eating on Their Show?

A Look at the Emmy It Girls of the Past 20 Years: Taraji P. Henson, Tina Fey, and More

Major Skin Mistakes You're Making in Your 20s, 30s, and 40s