Black Women Make 42 Percent Less Than White Male Counterparts — And Here’s What Companies Should Be Doing About It

The gender pay gap is a common topic of conversation in corporate spheres, despite the slow clip at which companies are moving to change it. But add race to that and, for Black women in particular, the reality becomes even more dire.

This late stage in the year, when summer turns to fall on Sept. 21, signifies the approximate extra time Black women have to work into 2022 in order to earn what their white male counterparts had earned by the end of 2021. Hence its recognition as Black Women’s Equal Pay Day.

More from WWD

To mark it, Essence partnered with Sheryl Sandberg-founded LeanIn.org, a nonprofit promoting gender equality, for a discussion of the facts and the impact.

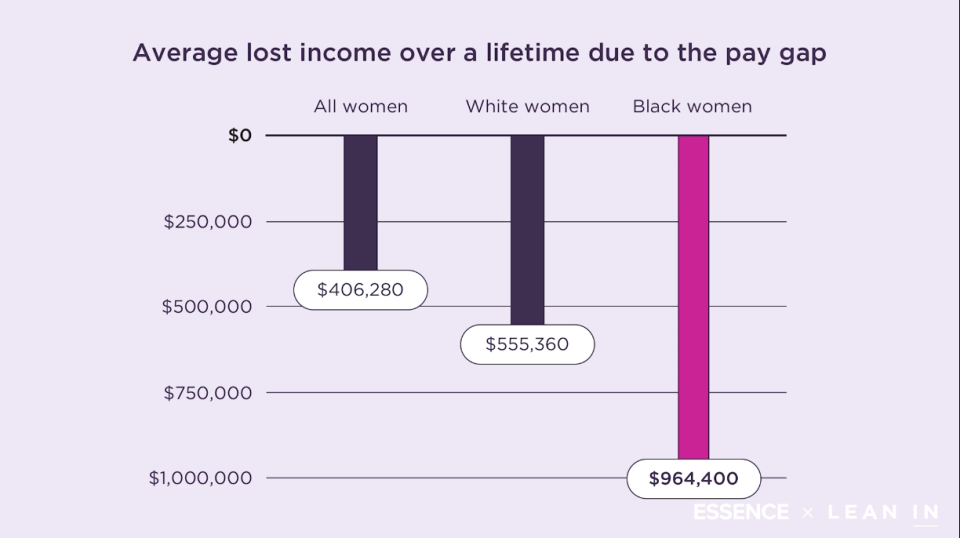

“Equal Pay Day is not just about a single check, it’s about how much money Black women lose out on,” said Nikki Tucker, head of social at LeanIn.Org, who hosted the talk. “And Black women lose out on around $1 million in income over the course of their lifetime.”

[Read more on what this means for the gender retirement income gap.]

More specifically, that’s more than $964,000, according to Lean In, which cited stats from the National Women’s Law Center. And by contrast, white women are losing out on $555,000 over their lifetimes compared to white men.

Black women earn 58 cents for every $1 a white man earns, or 42 percent less (that’s 21 percent less than white women).

For Pauline Malcolm-Thornton, chief revenue officer at Essence, who spoke during the video discussion, she’d thought sales would be the best place to realize balanced pay prior to her role at Essence, but that didn’t turn out to be the case.

“When I moved into management, we were all talking about how much we made. I had a larger team than what [my white male colleague] had at that time, so I was deeply disappointed and thought all along that this was truly a meritocracy. I’m in sales, numbers don’t lie. I had the highest-performing team and here I am being paid almost $100,000 less than my white counterpart,” she said.

The discrepancy was substantial, and only after independent research among female peers to determine going comp salaries and a real-talk negotiation with her higher-ups, was Malcolm-Thornton able to realize what she called a “course correction” with her salary. And it still took a year for that negotiation to reflect in her paycheck.

Katrina Jones, vice president of people and operations at Lean In, experienced being underpaid relative to someone her junior before joining her current role. And for Erika Bennett, chief marketing officer at Essence, who said she “negotiated the hell out of” a role she was stepping into before her current one, HR then told her never to tell anyone what she was making, despite that being a protected activity under the U.S. Department of Labor’s Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs and Executive Order 11246.

“It’s a means to keep people in certain positions from claiming what is right for them,” Bennett said.

The problem of Black women’s equal pay is one that runs deep. With Black women accounting for fewer than 2 percent of VP-level and C-suite roles, as well as having the largest share of student loan debt in the U.S., according to Lean In, the long-term impact on financial stability in Black communities is outsized.

One link in the corporate chain that’s fueling these facts, according to Jones, is that Black women aren’t being promoted.

“We talk about that middle rung and why it’s broken — Black women are not getting promoted, are less likely to get promoted and they’re also just opting out,” she said. “When you look at those numbers you’re seeing Black women become entrepreneurs, which is amazing, but I wonder often how many have stepped off their career track because it’s just too much.”

Bennett said she interviewed for chief marketing officer roles for two years, being turned away time after time because the key prerequisite was having held the position before. It was Essence owner and entrepreneur Richelieu Dennis who gave her the opportunity based on her body of work and what she would bring to the organization.

Seconding that, Malcolm-Thornton said, “Like Erika [Bennett], I would get that VP or SVP role but not the top C-level job because they always felt more comfortable with a white man in that seat, in my experience.”

Solving for Black women’s equal pay, much like women’s pay in general, will not have a quick fix, but companies need to actively prioritize it. And increasingly, a more and more conscious workforce won’t allow for anything less.

What companies need to prioritize, according to the panelists, is pay transparency, mentoring beyond the entry-level, flatter organizational structures that allow for more employees to meaningfully contribute and be heard, and real, equitable professional development and promotion tracks that prioritize representation where the company lacks it most.

For Black women, Malcolm-Thornton recommends prioritizing keeping a professional network to stay informed on comp salaries, starting high in salary negotiation (“if you’re trying to land at $350,000, you start at $425,000, $450,000″), and asking the right questions in the interview process, like how does the company promote and how does it treat employees in certain situations.

“I think part of the pay gap discussion has to be about Black women being able to show up fully and completely, but as themselves and that that is enough to garner the salary that we deserve based on what we bring to the table,” Bennett said.

According to the American Association of University Women, a nonprofit fighting for women’s advancement since 1881, Native Women’s Equal Pay Day is Nov. 30, and Native women are paid 50 cents for every white man’s $1. And Dec. 8 marks Latin Women’s Equal Pay Day as they are reportedly paid 49 cents for every $1 a white man earns.