New rules limit cancer-causing chemical in SWFL. What's the latest? Are they working?

With beefed up controls and a new federal rule designed to limit exposure to ethylene oxide on the books, Southwest Floridians have more protection from the potent carcinogen than they did a year ago.

Yet concerns remain. Learning whether more than a decade of emissions harmed them is all but impossible, as is successfully suing the companies that may have exposed them.

The chemical is critically important to medicine. It's used to sterilize equipment ranging from catheters to scalpels at area facilities including Arthrex in Ave Maria and LeeSar/American Contract Systems in central Fort Myers.

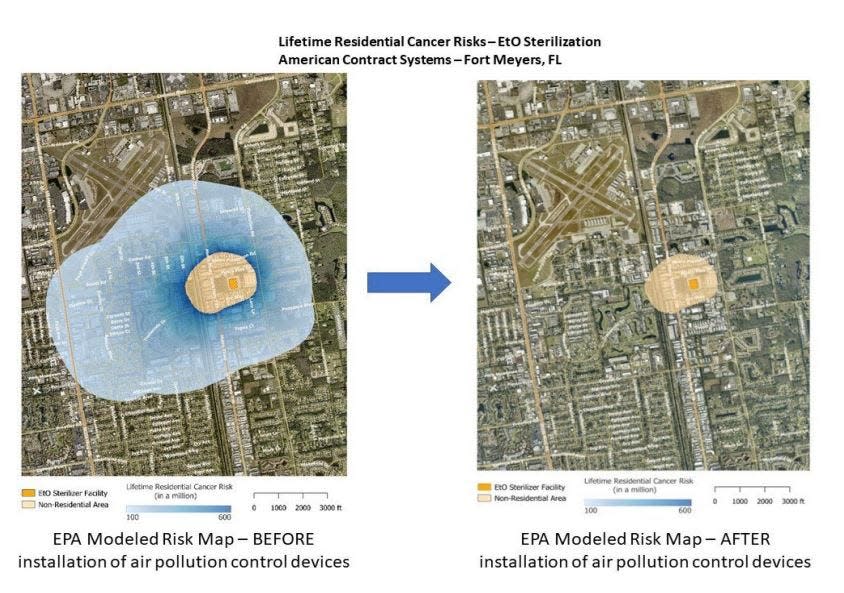

Alarm focused on the latter plant last summer, when the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency began warning it was concerned about the company's discharges of the invisible gas into the surrounding neighborhood. EPA mapped a fallout zone encompassing homes, schools and other businesses: Evangelical Christian School, Chico's FAS headquarters (including its employee daycare), Hideaway Country Club and Villas Elementary School.

A new worry out of the blue

A year ago, ethylene oxide, often called EtO, likely wasn’t atop most Southwest Florida residents’ to-worry-about list, but when news broke that the cancer-causing gas had been in its neighborhood skies for more than a decade, things changed.

In short order, residents learned the American Contract Systems plant on Adelmo Lane in the Villas was releasing "high levels" of the chemical, which new data revealed was "more toxic than previously understood," according to the federal agency. They also learned that if they wanted to weigh in on a proposed federal rule change (the one that's now law) about the chemical, they had just days to do so.

It all just came out of the blue, said Fort Myers Montessori School mom Alex Horn, who scrambled to educate herself about the risks. It wasn't easy. In a mailbox and online public information campaign, the EPA warned that "certain communities near commercial sterilizers could have elevated cancer risks due to lifetime exposures" and that it had "serious concerns." Two webinars, offered with scant notice, afforded concerned residents the chance to learn more.

Medically important as it is, ethylene oxide is scary stuff. According to the EPA, when inhaled it can cause cancers in humans including lymphoid cancer plus tumors of the brain, lung, connective tissue and uterus. “Human occupational studies have shown elevated cases of lymphoid cancer and, also breast cancer in female workers," it reports. It also has been linked to neurodegenerative disease and seizures.

The EPA's process for changing the rules around the chemical's handling was supposed to allow public input, but no one in Southwest Florida was notified until less than a week before the deadline. That's because the Fort Myers plant's emissions caught the agency by surprise, Jeaneanne Gettle, acting director of EPA’s eight-state Region 4, told The News-Press. “We were not aware of this initially, but we are now." The agency was concerned about the risk, which she characterized as high. "We are taking this risk seriously (and) will continue working until the risk is reduced.”

Officials got an earful four months later, when they came to Fort Myers for an in-person meeting.

The rule published last month in the federal register will "slash toxic emissions of ethylene oxide and reduce cancer risk," the EPA said in a release.

Scrubbers effective, but then what?

In Fort Myers, that risk reduction happened earlier than the agency required. After years of discussing upgrades, ACS installed new emissions filters designed to remove almost all of the pollutant. After going to see for himself in July, U.S. Congressman Byron Donalds (R-Naples), who'd met with concerned citizens and written to the EPA, released a memo voicing confidence that the new dry bed scrubbers were "99.9% effective" in removing the chemical.

Three concerns remained:

Determining whether past exposure had made residents sick or would sicken them in the future

Getting compensated for that harm

Determining if warehouses used to air out the sterilized equipment were dangerously emitting as well.

What about the warehouses?

Advocacy groups have raised the alarm about those facilities, which weren't included in the federal rulemaking. And some of them were serious polluters. "When Georgia's environmental protection agency did modeling around one warehouse, they found it emitted nine times the ethylene oxide as the sterilizer itself," said Daniel Savery, a senior legislative representative for the environmental nonprofit Earthjustice.

Even if emissions from the actual processing of implements may be curbed, once equipment is sterilized with EtO, it must go somewhere else to off-gas: essentially an airing-out to get rid of the residual chemical. These facilities, usually warehouses, release ethylene oxide too, as do transport trucks, but neither is regulated by the EPA.

Though Savery and others say no level of EtO exposure is safe, if it can't be eliminated, companies should test for its presence with what's called fenceline monitoring. As the name implies. it records levels of a pollutant at a facility's borders.

How worried should neighbors be? Fort Myers plant released carcinogens for 12 years.

Medical equipment manufacturer Arthrex has such a warehouse a few miles away on Plantation Road in south Fort Myers. Since 2014, it's been doing just that, as it has at its Ave Maria plant since 2017, said David Bumpous, vice president of operations, in a statement: "Arthrex is committed to protecting its employees, the community, and the environment. Regularly scheduled internal and external (fence-line) monitoring is conducted at our processing facility and our logistics center located in Fort Myers, Florida. Arthrex proactively performs these tests and implements process controls to ensure the safety and health of our employees."

Bumpous said the firm Fisher Phillips reviews the program and test results and the company also works with the Florida Department of Environmental Protection to "serve as a model for other commercial sterilizers across the state of Florida. Most importantly, Arthrex remains fully compliant with all Federal, State and Local regulatory requirements. Arthrex is dedicated to Making People Better, including the people that work and live near its facilities."

It's a start, Savery said, but he'd like to see more. "I see it as a three-step process. The monitoring is the first step, and it's very important," he said. "Step two is making the data available to the public and then step three is if results from the fenceline monitoring show unsafe levels of EtO that the company then reduces emissions to safe levels."

Bumpous said the corporation hadn't ever released that information to the public. "These are part of numerous industrial hygiene tests performed by Arthrex each year to ensure the safety and quality of its facilities and products. The data is reviewed by professional staff and provided to employees, consultants and regulators as necessary. The data is not provided to the public.”

Whether exposure made people sick ... and possible restitution

For those concerned about years of unwitting exposure, answers are hard to come by. We do know children are more susceptible to the toxic effects of ethylene oxide, science shows, since their cells are dividing more rapidly with greater potential for DNA damage.

After learning about the emissions and children, FGCU instructor and environmental advocate Cindy Banyai realized she may have found the reason for her daughter's previously inexplicable blood disease: Her children attended school and after-school activities in that zone throughout the period of unchecked emissions.

Her youngest daughter Evie, now 6, came down with autoimmune hemolytic anemia, a disease for which there's no family history, leading to a two-year battle that included multiple hospital stays, blood transfusions, four rounds of chemotherapy, respiratory failure and a seizure, leaving the family with thousands in medical debt. Because the disease was unexpected, Banyai had always wondered if there was a possible environmental cause. At one of the EPA's EtO meetings, her suspicion gelled. But it remained just that ‒ a suspicion ‒ because tests to measure past exposure and future risk are nearly impossible to come by and imperfect, the EPA admits.

"Unfortunately there is not an easy or an effective test that can measure whether or not someone was exposed to EtO in the levels we would expect to find in the air near these facilities, even near those like the one in Fort Myers where EPA modeled risk at elevated levels," wrote spokesman James Pinkney in an email. "EtO levels that are high enough to be associated with a predicted increase in risk over a lifetime, does not necessarily mean that those levels would be high enough to be able to be tested for at a doctor’s office.

Pinkney cited a CDC brief that said "Specific tests for the presence of ethylene oxide in blood or urine generally are not useful for clinical decision making. These tests cannot be used to predict if an adverse health effect will occur, or the type or severity of health effects that may result from exposure are not available by most commercial laboratories and not done in a physician’s office."

It's for that reason that Florida lawyers are generally reluctant to take such cases, as Banyai found out when she started asking around. The state's standard for evidence is much stricter than what the existing imperfect testing for EtO exposure could prove, and she found no attorney willing to take on a suit.

All of which leaves Banyai disheartened. "Even with the research, even with a fairly well documented connection, no doctor will come forward and say, 'Yes, it's definitely connected,' and so lawyers don't want to take the cases," she said. "So I'm disappointed, because I feel like this was swept under the rug (and) people who are trying to shine a light on it are not supported. It felt like shouting into the void."

This article originally appeared on Fort Myers News-Press: Fort Myers was exposed to cancer-causing fumes for 12 years. Now what?