Wilmington with two school districts? Delaware’s latest redistricting vision to take shape

He isn’t tired.

Jea Street sifted through decades of memory — preparing Black families for desegregation, fighting school closures, pushing for equitable funding inside Wilmington city limits — as he listened to some of the same discussion he’s heard for 20 years.

Back in the late 1970s, the grizzled community advocate watched his school district get chopped into four new pieces under court order. He watched bus routes retrace, only to dramatically change all together. He watched Delaware demand and seemingly unravel the very progress of school desegregation in its largest city.

Back at a computer screen, the latest state consortium meeting hummed along over Zoom. The New Castle County councilman was asked to speak to historical context of redistricting at the spring meeting, which is easy enough when history echoes in his ears.

He isn’t tired, he says. “I'm angry.”

Street has been working around Delaware education for nearly 50 years, winning statewide honor for that service earlier last month.

“I’m one of the few people who spend this amount of time in the arena, and I'll never be able to say: ‘I'm leaving, and I'm leaving it better that I found it,’” he said, days after one March meeting.

“And that’s because the whole process was a total failure.”

Bound by a history of failures, mirrored perhaps in attempts at change, the latest effort to demand better for city students is coalescing around a defining charge: redistricting schools in Wilmington.

The Redding Consortium is developing a redistricting strategy, now sending “interim plan” or framework to present to the state board, with a formal proposal to follow. As of early May, members have officially voted to remove Christina School District from the city in their plan, plan engagement and lay out a timeline.

The vote to remove Christina was 18 yes, two no and two abstentions on May 9. What's next is subject to change.

Redrawing color-blocked maps still leaves the same challenges to line Wilmington’s streets. Opponents to the move fear a lack of detailed planning so far, while proponents say moving forward on addressing the fractured school governance will be a first, needed step in more systemic reform.

The consortium — created in 2019 to recommend policies like this aimed at educational equity in the city and northern county — comes in the shadow of several similar task forces, committees, different studies dotting the same lines since the turn of the century.

By 2001, "They Matter Most" report recommendations are not implemented; 2008, "Wilmington Education Task Force" recommendations are made without action; 2013, "Mayor’s Youth, Education and Citizenship Strategic Planning Team" issues no final report; 2014 brings "Wilmington Education Advisory Committee" creation. By 2015, a "Wilmington Education Improvement Commission" begins recommending Red Clay absorb Christina, leading another comprehensive redistricting plan to make it all the way to legislature in 2016 — to lapse.

Members today don’t yet all agree on the right path forward. Beginning this summer, the group will separate into subcommittees focused on building a complete plan for redistricting to present to the state and ultimately the General Assembly.

There’s hope to capitalize on new momentum. Such a result has yet to be seen, in decades.

“As far as I'm concerned,” Councilman Street said of the latest plan, “it’s 23 years old.”

So what would this look like?

Consider the puzzle pieces.

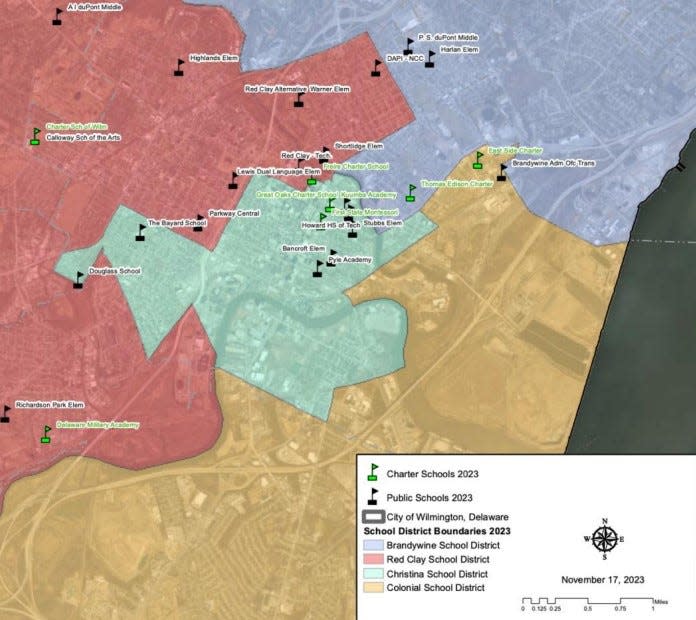

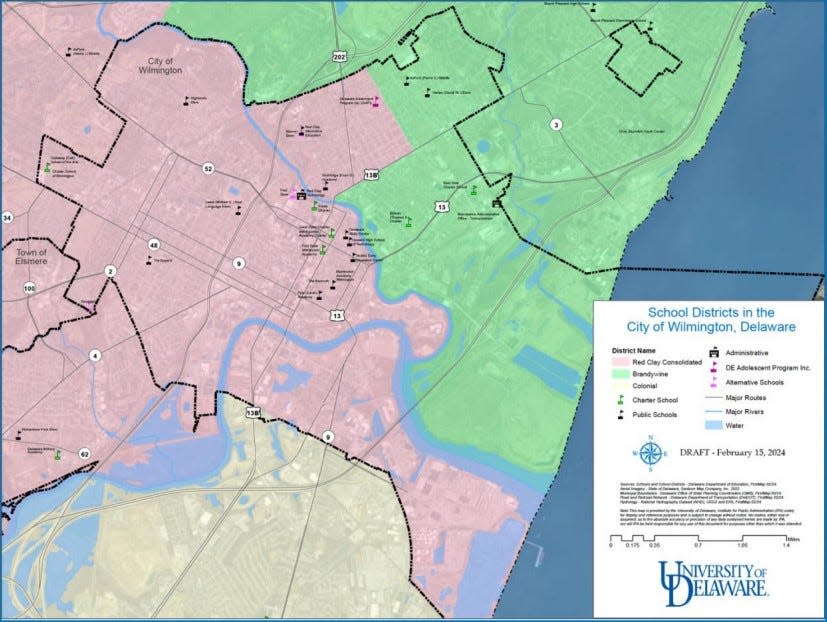

Since 1978, four school districts — Brandywine, Red Clay Consolidated, Christina and Colonial (later alongside smaller New Castle County Vo-Tech) — have shared responsibility of teaching over 11,000 children in Wilmington.

Locked around the city’s center, Red Clay hugs the western edge, Brandywine from the northeast, Colonial from the south, all cradling Christina’s piece toward city center, isolated from the rest of its Newark-area district.

Consortium membership had been working on a modified “River Plan” proposal, recommending all Wilmington students be served by Brandywine and Red Clay, while seeing Christina and Colonial removed entirely. By this month, though, they've pulled back to allow "more space and time" for a final strategy recommendation.

At last week's meeting, Christina superintendent Dan Shelton and Red Clay's Dorrell Green didn't cast a vote on removing CSD, while the other superintendents in the consortium voted in favor. Stephanie Ingram, president of the Delaware State Education Association, joined a parent member in opposition.

In some initial proposals, Red Clay would keep Warner Elementary and Shortlidge Academy to “ensure minimal disruption related to student movement,” according to a draft, while both it and Brandywine would expand current boundaries to absorb portions of other districts.

For now, any decision remains to be finalized. Some members have staunchly advocated for returning to one city district, others seem to hesitate with a redistricting vision all together.

Any proposal admits this would be a sizable undertaking for schools and communities, giving roughly five years of runway to make it happen, if passed. Transition plans would be expected, including plans for addressing student transportation, permitting students to continue attending the school they attended before boundary change and more.

It's early days. But none of this sounds entirely new.

‘Fear of change’

A patchwork of history radiates under Wilmington's current landscape.

On the heels of desegregation, a 1971 lawsuit ended with a court order that required a new bussing plan to send suburban students into Wilmington, and city students out, until the mid-1990s. Since the lifting of that order, and the Neighborhood Schools Act of 2000, experts say changes unfurled in state law have largely amounted to the resegregation of schools in Wilmington and its suburbs.

Charter, magnet, vo-tech, the School Choice Act of 1996: trickling decisions over decades further fueled this reality for these public schools. It has left Wilmington with several racially identifiable, high-poverty schools, per the consortium.

“For the quarter of a century since, these negative dynamics have continued,” the latest drafted plan reads, “harming multiple generations of Wilmington students and their communities.”

Today, city students are 69% Black, 54% from lower-income backgrounds and 23% living with a disability, according to consortium statistics. Those figures are higher than that of each Delaware county. They also experience higher rates of crime, housing instability and poverty — alongside educator turnover and persistent underachievement.

“I mean, there are so many intersecting histories that are challenging here,” Sen. Elizabeth “Tizzy” Lockman, consortium co-chair, back in April.

The Wilmington Democrat has served on all three groups previously exploring similar reform — first, Wilmington Education Advisory Committee, then a Wilmington Education Improvement Commission, now Redding Consortium.

Recommendations have always stalled.

“That is probably like the crux of it,” she continued. “I think it's just fear, fear of change — but it's a fear of change that's, quite frankly, a very justified trauma, based on past experiences."

Even with echoes across agenda, echoes across decades of reform attempts, Lockman hopes today's efforts land with a different narrative.

“This is not about some student population being a burden that someone has to be concerned about inheriting,” she said. “This is about: How do we create a context for transformative change that's going to benefit students across these school districts?”

‘A lot more than redrawing the lines’

By the end of May, members hope to form an interim plan.

Starting this summer, according to the latest draft, one subcommittee will focus on determining the exact redistricting approach. Recommendations will almost certainly show Christina removed from the city, though many details remain unsolidified.

The consortium will “publicly deliberate” proposals to come and vote, while other subgroups dig into operational planning, fiscal impacts both state and local, as well as community engagement events to come.

Such planning is now expected to last until fall 2025, “at the latest."

October 2025 is ear-marked for submitting a final plan to the State Board of Education, January 2026 a fiscal note, spring 2026 submission of a final plan to the General Assembly.

It stands to be a long, complex process. And if this is a puzzle, many want to see more than cutting new pieces.

“I think we kind of get caught up on ‘Oh, redistricting is going to be the magic bullet.’ That it’s going to solve the issue with how our students are persistently underperforming,” said Shannon Griffin, senior policy advocate with ACLU of Delaware for over 15 years. She hopes maybe this time Delaware can "solve a solvable problem," with greater parent and community input.

“But we can't fool ourselves into thinking that redistricting for redistricting sake is going to really have the kind of results that we want to see systemically, if we're not more focused on what's happening in those buildings.”

Consortium leaders agree, hoping to capitalize on a very similar body, charged with improving city schools — the Wilmington Learning Collaborative.

The new body, solidified in 2022, has aims to “unify a fractured state of public education inside the city and combat issues long plaguing its students,” as previously reported. It fuses efforts across three Delaware school districts and their nine elementary schools. And that work is just starting to heat up.

“With the potential redistricting of some of our schools on the horizon, I have been asked for my opinion and insights on what needs to be done in the interim to ensure smooth transition,” Executive Director Laura Burgos told a collaborative meeting last month. “None of these questions and decisions are easy.”

Penned in the draft interim plan, there’s hope WLC will supply “immediate help and assistance” to the Christina School District. That could range from educator support, reducing class sizes, boosting mental health intervention, math and reading specialists and more before redistricting takes shape.

Some believe students and families deserve relief, now.

“It's fundamentally unfair and flat-out rotten,” said Councilman Jea Street of the current system. “For 10 years you've had proficiency scores in major category areas from zero to less than 10%. They know that. And then bus them off to high school, knowing that they're destined for failure through no fault of their own.”

He tries to be optimistic, but: “You’ve got to do a lot more than redrawing the lines.”'

'We cannot normalize failure': Wilmington Learning Collaborative eyes lofty goals ahead

Got a story? Kelly Powers covers race, culture and equity for Delaware Online/The News Journal and USA TODAY Network Northeast, with a focus on education. Contact her at kepowers@gannett.com or (231) 622-2191, and follow her on X @kpowers01.

This article originally appeared on Delaware News Journal: A vision for school redistricting in Wilmington is taking shape, again