Why Operation Plunder Dome lives on after 25 years

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

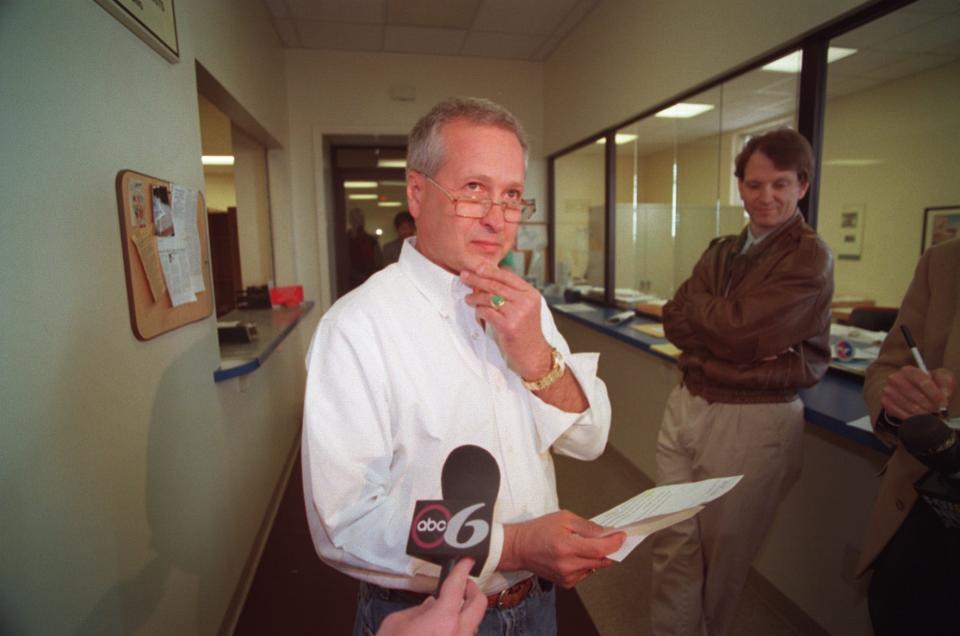

PROVIDENCE – On the morning of April 28, 1999, FBI agent W. Dennis Aiken arrived at a historic brick carriage house on the East Side and met the owner at the door: Mayor Vincent A. “Buddy” Cianci.

It had been a few years since one of the FBI’s foremost experts on public corruption made his return to Providence. Now, dozens of his fellow agents were downtown swarming through City Hall and making the first arrests in a municipal corruption probe bursting into view.

The feds dubbed it Operation Plunder Dome.

“I wanted to catch Buddy before he heard they were in there,” recalls Aiken, speaking in his easy Mississippi drawl. “I wanted to see what he would tell me. Guys like that, guys like Buddy, they always say they’re going to take the Fifth, whatever, and they always got something to say if you catch them by surprise. They can’t help themselves.”

On that day 25 years ago, Cianci didn’t give up anything at his doorstep. “He was surprised but he wasn’t shocked” to see Aiken. “I think he’d been waiting for me to knock on his door for a long time.”

'The level of corruption here was unbelievable'

Providence's longest-serving mayor – and arguably its most charismatic and recognized felon – was indicted in April 2001 on charges of running City Hall as a criminal enterprise. (Cianci was forced from office in 1984 after admitting he had assaulted a man he'd summoned to his home and then thrashed for consorting with his estranged wife.)

By the time of Cianci’s Plunder Dome indictment, the investigation had already led to convictions against six city officials for crimes that included bribery and extortion in exchange for tax breaks, an award of a school department lease, and preferential ranking on the list of tow truck operators used by the city.

The investigation spread into the police department, where evidence showed that promotional exams and admission into the police academy could be bought with political contributions.

Eventually, nine city officials would be found guilty in Plunder Dome, including Cianci, convicted of a single count of racketeering conspiracy.

“I’m from Mississippi and pretty familiar with the levels of corruption,” says Aiken, now retired. “But the level of corruption here was just unbelievable.”

Political scandals were everywhere, but none came close to Cianci

Political scandals oozed openly from Rhode Island corners around that time.

On the same day the Plunder Dome raid splashed across The Journal’s front page, the newspaper also carried a story of former Gov. Edward DiPrete, imprisoned months earlier for racketeering, bribery and extortion, getting a work-release job.

Pawtucket Mayor Brian J. Sarault preceded DiPrete to prison by a few years for extorting money from city contractors. Other corruption convictions would follow Plunder Dome: House Speaker Gordon Fox, Central Falls Mayor Charles D. Moreau, three North Providence Town Council members, two General Assembly lawmakers – the list goes on.

But none generated the same fascination or national headlines as the Plunder Dome prosecutions of the beguiling Cianci – and his central-casting band of city officials caught in taped conversations taking or arranging bribes.

“It was very difficult to attack the tapes,” says Aiken flatly.

The list goes on: RI has no shortage of politicians convicted of crimes

Unlike other indicted public servants, Cianci – who in between felony convictions and after leaving prison in 2007 enjoyed a second career as a savvy radio talk show host – never shunned the spotlight.

One morning during his 2002 trial, when the judge gave the jury the day off, Cianci made one of his periodic appearances on the national radio show “Imus in the Morning." This time he appeared in person as the show broadcast that day in front of 800 people in the Biltmore Hotel, just across Kennedy Plaza from the federal courthouse.

Imus joked that he’d like to “hang around here today and launder some money.” Cianci never wilted. “I pleaded not guilty, and I expect to be found not guilty.”

Imus told the mayor he hoped he “got off.”

Some people were "mesmerized" by Cianci, the comedic rogue, Aiken says. “Some politicians have a cult-leader personality, and they have the skill to cause people to do things not in their best interest, but for theirs.”

Why does Plunder Dome live on?

Many of the city officials who went to prison have died now. But, like any good story, Plunder Dome has legs.

Former Providence Journal reporter Mike Stanton, part of a team at The Journal who covered the trials, wrote a bestselling book in 2003 about the rise and fall of “The Prince of Providence" (which later became a play).

Buddy’s life became the basis for other theatrical performances, including “'Buddy' Cianci: The Musical,” which ran in New York City.

And in November 2016, almost a year after Cianci died at age 74, a podcast called "Crimetown” debuted, telling the tales of crooked politicians and wiseguys. The series began – where else? – but in Providence, home to both. The Plunder Dome investigation and Cianci take center stage in several episodes.

“It’s one of the most successful podcasts ever,” with more than 40 million downloads and counting, says Marc Smerling, who created "Crimetown" in partnership with Gimlet Media. “People are still listening.”

Using some of the 100 hours of conversations secretly recorded by the FBI's undercover witness and Providence businessman Tony Freitas, the "Crimetown" episodes resurrect the voices of Cianci, and city officials participating in various felonious pursuits.

Among them:

Joseph A. Pannone, chairman of the Providence Board of Tax Assessment Review, who told Freitas that for the right “campaign contribution” he could win favors from Cianci’s chief of staff, Frank E. Corrente. “You’re lucky you know me,” Pannone chortles.

David Ead, the tax board’s vice chairman and a former cop, who tutored Freitas about avoiding the word “money” on phone calls. It’s a “thing.” Ead told Freitas the city would sell him two property lots with a condition: “How much you want to give to the man downtown?” to grease the deal.

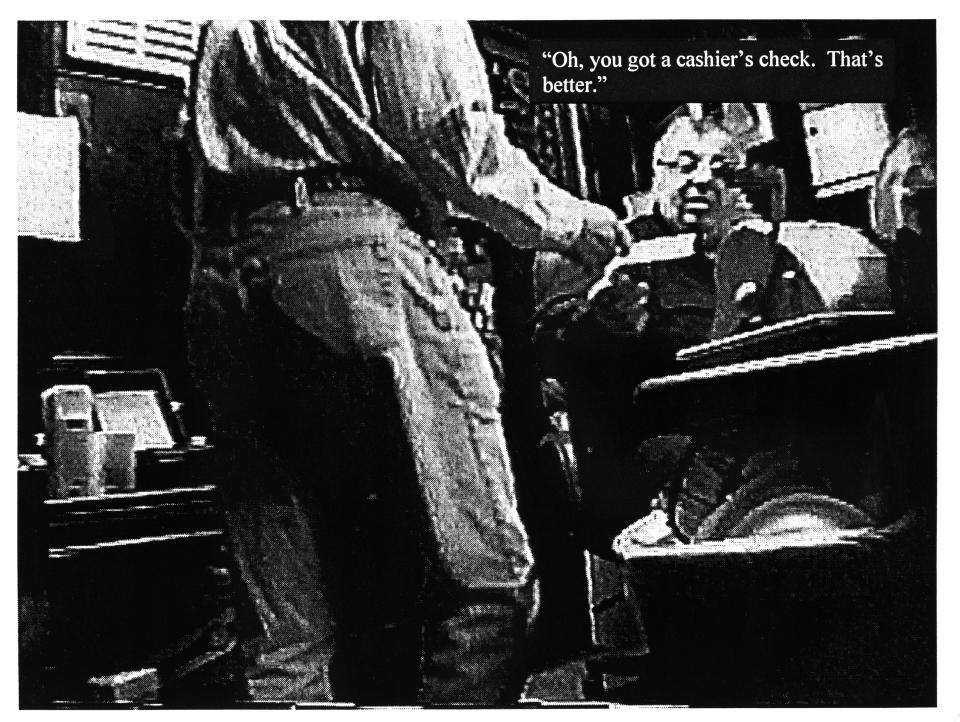

And there was Corrente, famously caught on video from a hidden camera in Freitas' briefcase taking an envelope of $100 bills from Freitas to secure a school department lease for one of his properties. You can still watch the four-minute clip on YouTube.

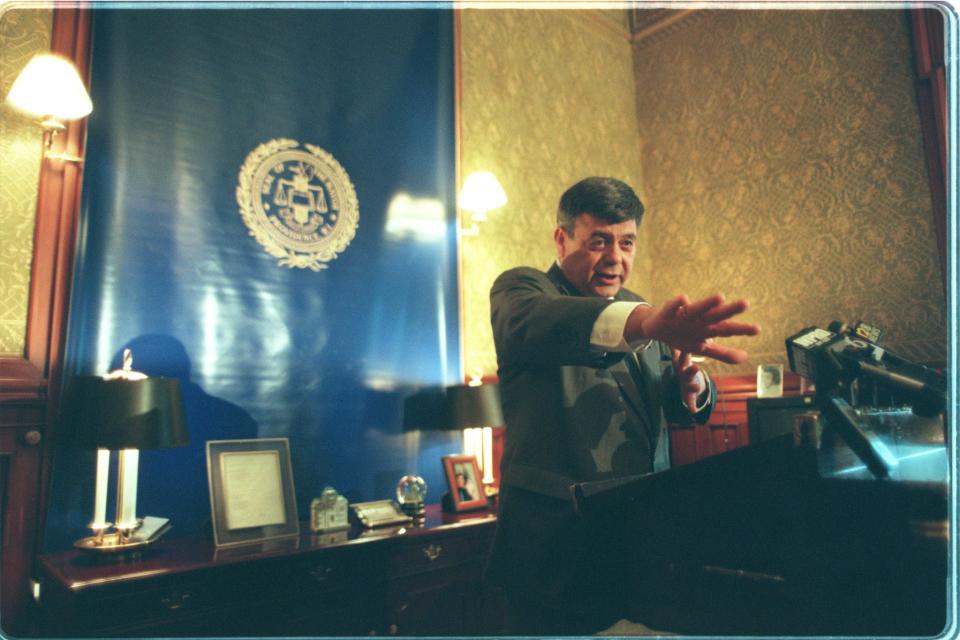

People remember the Plunder Dome investigation, says Smerling, because they remember Cianci, this “Shakespearean character who is flawed but loved.”

“He is the son of Providence. I think that’s it. He represents the old Providence: the backroom, the handshake deals, the money under the table.” But he was also “so charismatic you couldn’t stop believing in him. Providence believed in him. And for a long time, he delivered, and everybody just looked the other way, because corruption was such a fabric of the city, it didn’t really bother a lot of people. Plunder Dome was just like: ‘Yeah, we knew that.’”

Has Providence changed since Plunder Dome?

John Marion flew to Providence for the first time in spring 2001 with his wife, Karen Ng, who had accepted a physician's job here.

“I remember turning on the news, and it was all about the leak of the [Corrente] tape, and there’s a briefcase, and a tow list and I’m like: 'What the heck was I getting myself into?’”

Marion, who now heads the good-government group Common Cause Rhode Island, says Rhode Island didn't invent corruption. But it is one of the few places that "developed an outsized reputation for corruption in large part because of Cianci's performative corruption.”

With a wink to his many admirers, “he made corruption part of his personality.”

Cianci was known for presiding over the city’s revitalization, says Marion, but he was also known for "how he engaged in corruption in his political career.”

A federal investigation of Cianci's administration in the 1980s led to two dozen convictions.

Cianci was a “Trump prototype,” says Marion. “A melding of entertainment and politics.” He wasn’t the first corrupt American politician in that respect, “but Buddy was the one who played to the cameras, unlike everyone else, and that really, to me, was the difference.”

Soon after Marion and his wife bought a house in Providence, they had an issue with a tree by the curb. Marion called the city to cut it down and then called later to have the stump removed, only to be told there might be a way for him to move up on the “stump list” if it bothered him so much.

“They were essentially soliciting a bribe,” he says. “That was my first interaction with city government, and those were the closing days of the Cianci administration.”

Providence has changed since Plunder Dome, says Marion. The city proved it in 2014 when voters rejected Cianci’s post-prison attempt to become mayor again.

“There were certainly some voters who went for him, but I think Providence had changed in large part. It became in some ways the Renaissance city [Cianci] took so much credit for. It was full of new people who didn't want to return to the older Providence and those that accepted his old behavior.”

'Don't these people pay attention?'

Margaret E. Curran enrolled recently for a class at the Providence Art Club. Soon after, the instructor came over and said: I know you. You prosecuted Buddy Cianci.

“Yes,” Curran confirmed, “I was the U.S. attorney at the time.”

Curran had been an assistant U.S. attorney for many years when, in May 1998, she was chosen to head the office. She remembers the day she was briefed on the secret operation called Plunder Dome.

“I was like, ‘Yes!'” recalls Curran. “I think that everyone in federal law enforcement had for years thought there was a lot of bad stuff going on with Cianci, but it was impossible to get anything good enough” to convict him.

Plunder Dome remains Rhode Island’s “most prominent and notorious" of corruption investigations, says Curran, “mostly because it got so much more attention. I mean, getting interviewed for '60 Minutes' was not a usual aspect of most of our cases.”

In December 2002, six months after U.S. District Judge Ernest C. Torres sentenced Cianci to five years in prison – comparing him to a “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde” character – the CBS news magazine aired a puff piece on Cianci.

Seemingly enthralled by the wisecracking pol, the show allowed Cianci to lie about the details of the assault case that forced him out of office in 1984 and left unchallenged his version of his racketeering conviction.

Curran defended Cianci’s prosecution, noting that while the government never produced evidence of bribes landing directly into Cianci’s hands, “he was closely involved" with his subordinates who did.

Did Plunder Dome serve as a deterrent against other public corruption?

“I have asked myself the same thing,” Curran says. “When I started in the U.S. attorney’s office, I thought public corruption cases could really have some deterrent effect. But even as we were investigating the Cianci case, there was other [public corruption] stuff going on, and it was like, ‘Don’t these people pay attention? Doesn’t this have any impact?’”

What was it like being mayor after Cianci?

The stigma of Plunder Dome altered how Angel Taveras ran the mayor’s office when he arrived in City Hall in 2011.

He remembers a public event he attended early in his tenure when a woman approached him and handed him an envelope.

“I kind of freaked out a little bit,” Taveras says. “I told my staff: ‘Don’t ever put me in that position again. I don’t want people handing me envelopes.’”

The envelope turned out to be an invitation to another event, but his reaction to it had everything to do with the stain of Plunder Dome.

“I don’t think I would have done that,” Taveras says, had the taking of an envelope not come to symbolize the way of doing business in the Cianci administration.

“I tried never to meet alone with anyone; I always wanted to have staff with me,” Taveras says. “I thought it was important to be careful.”

In 2014, when Taveras was running for governor and Cianci was making his failed redemption run for mayor, FBI agent Aiken complimented Taveras’ City Hall administration: “The perception of the rest of the country is that the city has changed. The Taveras administration is very honest.”

“That made me feel very proud,” Taveras says.

Like several former U.S. attorneys and good-government groups, Taveras opposed Cianci’s bid to become mayor again in 2014.

“I didn’t want the city taking a step backwards, and that’s what I saw if Buddy was reelected,” says Taveras. Plunder Dome “was a dark moment in our history. I also feel a lot of people knew but few people wanted to do anything about it. Kudos to the Justice Department and Tony Freitas.”

How did Plunder Dome go down?

The undercover aspect of the Plunder Dome operation lasted more than a year until one day, Ead, the tax official, arrived at Freitas’ heating and air conditioning company office. (Freitas' FBI code name was "Mr. Freon.") He insisted over and over that all that previous talk about the "big man downtown" was a test. "There is no big man." Then he asked Freitas to walk out to his car with him.

Before he did, Freitas grabbed his pager on the desk that was rigged with a hidden microphone.

It picked up Ead saying he had received a call the previous night from a woman who told him Tony Freitas was working with the FBI.

Freitas sloughed off the accusation, joking that he was working for the CIA, not the FBI.

It seemed to appease Ead, but Dennis Aiken knew then that the undercover part of the investigation was over.

Within weeks, agents were swarming through City Hall on that April day 25 years ago.

Ask Aiken, who retired from the FBI in 2007, if Operation Plunder Dome was a deterrent to other corruption and he is unequivocal: “No.” He chuckles.

“I’ll tell you. I participated in a lot of things about what causes corruption and this and that. People write papers, and there’s all types of material out there. But what it really comes down to is greed and power. When you have those two things, which are part of human nature, you’re always going to have somebody in public office looking for an opportunity to take something that doesn’t belong to them.”

Contact Tom Mooney at: tmooney@providencejournal.com

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: 25 years later, the legacy of Operation Plunder Dome and Buddy Cianci