Why it’s so important for us to read banned books this week (and always)

Why it’s so important for us to read banned books this week (and always)

When I was a little kid, my mother read books to me and my brother every night before we went to bed. She told us the story of Wilbur and his best friend Charlotte, and the story of Charlie Bucket and his golden ticket into that magical candy factory. My mother wanted us to gain an affinity for reading — she knew how important it was to instill that love in us.

As I grew older and read more, I understood why reading was so important — not just to develop a larger vocabulary or pass the time when I was bored in high school. And it wasn’t so I could have a talking point or common interest with another person. Although those are all fantastic benefits of literacy, the more I read, the more I realized that books are important because they give us perspective and a better understanding of people.

Sure, escapism is what generally draws people to a book. Reading is a way to take ourselves out of our every day lives and instead focus on someone else’s story. But books are also a means to discover or understand something that we simply aren’t as familiar with as we would like to be.

That’s why it so necessary that we acknowledge this week, Banned Books Week.

A photo posted by Rebecca Skloot (@rebeccaskloot) on Sep 28, 2016 at 12:37pm PDT

Books have been banned for as long as they’ve been in print. As humans, we tend to shun anything that gives light to a subject that makes us uncomfortable in any way; sexuality, racism, abuse, horrifying moments in history, suicide, mental health issues, etc. Religious groups, and even some parent groups, don’t want their children to read a simple story involving magic — it “may turn them down a bad path.”

But it’s those kinds of books — the ones that give us insight into the human mind, the ones that reveal what makes us tick, the ones that represent the entire spectrum of human emotion: the good, the bad, the ugly — those are the books that we need to read most of all.

Of course, it’s those books that we find on this list.

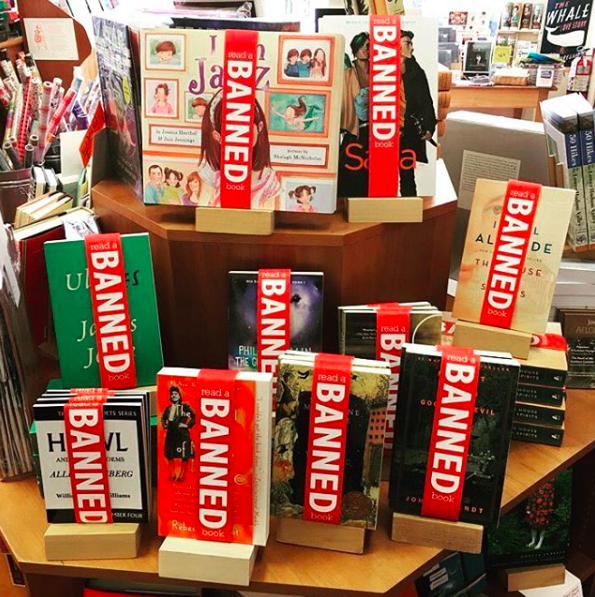

A photo posted by AMAB (@amabbooks) on Mar 9, 2016 at 2:32am PST

If you take a look at the list of commonly banned books for Banned Books Week, you’ll find plenty of your high school classics on there. Beloved by Toni Morrison is banned for its violence and sexual content. The Catcher in the Rye is considered foul, filthy and obscene — God forbid a teenager expresses an uneducated opinion and experiments with curse words. Ernest Hemingway’s somewhat autobiographical A Farewell to Arms was considered lewd and profane despite its honest depiction of World War I. To this day, The Scarlet Letter is viewed as sinful and immoral as it encourages adultery and goes against community values. Some say To Kill a Mockingbird promotes white supremacy.

The list of banned classics is extensive. Alice in Wonderland and Animal Farm were originally banned because animals were portrayed to be as intelligent as humans — which seems absurd by today’s standards. We may even question why books that vaguely depict sex or drug use are still sometimes banned in a society that so regularly utilizes the Internet (where there is a video for everything).

A photo posted by Kathe Izzo (@theloveartist) on Sep 29, 2016 at 3:00am PDT

However, it’s not just classics that get slapped with a ban. Modern YA is often burned by the bright red ban.

One of my favorite books is The Perks of Being a Wallflower by Stephen Chbosky. Through letters to an anonymous recipient, it tells the story of Charlie, describing all of the ways his life is changing now that he’s in high school. He has to navigate his shyness and slight awkwardness. He learns how it feels to fall for a girl, how great it feels to find friends that help you belong. He discovers sexual urges, and realizes that, sometimes, our minds trick us into forgetting something that changed us.

This is book is pretty commonly banned because of its frank descriptions of both sex and sexuality, its characters’ use of drugs and alcohol, and its topic of sexual abuse. Of course, these subjects all lend themselves to Charlie’s overall mental health and his eventual breakdown. But to actively ban those ideas is ridiculous. When you’re an adolescent, you are bound to be confused about who you are and who you find yourself attracted to. I don’t know anyone who didn’t think it was cool to sneak a bottle of cheap vodka to a high school party when they were teens — we all wanted to make ourselves feel just a little bit older.

A photo posted by Textbooks.com (@textbooks) on Sep 28, 2016 at 1:52pm PDT

Another commonly banned work of literature is the Harry Potter series. We all know the story of the Boy Who Lived and his adventures to save the wizarding world. Many parents and religious groups believe the story promotes witchcraft and sets bad examples — Harry and his friends frequently disregard the rules and put themselves in dangerous situations. So, I guess girls reading intelligent, determined, strong yet vulnerable characters like Hermione, Ginny and Luna doesn’t matter to the folks banning the books? And the fact that Neville overcomes his fears and insecurities, all while remaining steadfast and loyal, apparently means nothing. And themes of love and friendship don’t seem to topple the fear of a stick shooting colorful sparks.

A photo posted by @bannedbooks4life on Sep 27, 2015 at 2:34pm PDT

But adolescence isn’t solely a time of love and friendship. Adolescence is an extremely difficult period, and literature can help young people cope with the darkness.

13 Reasons Why is a frequently banned book (alarmingly so), but it is so important that teens read it. The book tells the story of Clay Jensen, who hears the collection of tapes Hannah Baker recorded before her suicide. Hannah posthumously sends these tapes to the people she feels directly contributed to her decision.

Teen suicide is, sadly, not a new occurrence, but with the rise of social media and incessantly cruel cyberbullying, more teens are taking their own lives. Hannah commits suicide because of a rumor that spirals out of control and results in harsh treatment from her peers.

This is a shared experience among suicide victims, and books like 13 Reasons Why provide insight into the mind of a young person who can’t see any way out of her anguish.

It’s important for teens to understand the power of their words and the deadly seriousness of cruel gossip — so they need access to these types of stories.

A photo posted by Books Food Sewing | Marissa (@raegunramblings) on Sep 28, 2016 at 8:51pm PDT

Love and Other Four Letter Words by Carolyn Mackler, among so many other novels, has been banned for its graphic passages about masturbation — despite most young people discovering their sexuality in this way. Benjamin Alire Saenz’s truly stunning novel, Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe, shows two sides of teen homosexuality: out and proud, and scared and unsure. It’s banned. If a book mentions politics, abortion, rape, etc. — then it is going on the list.

These are the stories that we need to be reading. They’re the stories that bridge the gap between blind ignorance and empathy.

Banned books shed light on frequently unvoiced subjects, greatly helping folks to better understand a life different from their own. An upper middle class white girl might not understand the hardships of a Muslim girl facing Islamophobia at school, or a Latina girl trying to get into this country, or a black girl just walking down the street.

A photo posted by Alachua County Library (@alachualibrary) on Sep 29, 2016 at 11:59am PDT

Banned Books Week brings these stories to the forefront — reminding us that the most important works are typically the most controversial. People forget that their version of right and wrong or moral and immoral isn’t the same as everyone else’s. We want future generations to be empathetic and open-minded, well educated and ready to learn. We can’t do that without discussion, and these books breed the best discussion.

So start reading some banned books!

The post Why it’s so important for us to read banned books this week (and always) appeared first on HelloGiggles.