Why the extreme Louisiana floods are worrying but not surprising

The Louisiana floods, which have now killed at least six and led to the evacuation of 20,000, were the result of a bizarre confluence of weather events that are becoming suspiciously more common as the planet's climate continues to warm.

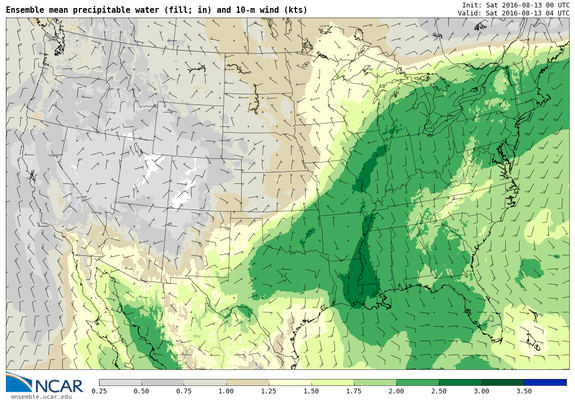

First off, the atmosphere was primed for heavy rain for days on end along the central Gulf Coast, with precipitable water values (the amount of water vapor in a column of air above a specific location) hitting record levels in Louisiana — beating out readings seen during tropical storms and hurricanes going back to 1948.

SEE ALSO: Louisiana residents make best of 'historic' flood on social media

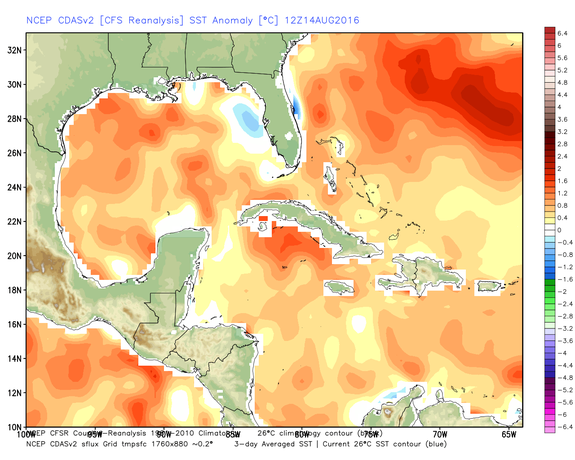

A near-record warm Gulf of Mexico helped add water vapor to the air, with bathtub-like water temperatures near 90 degrees Fahrenheit in parts of the Gulf.

Another factor contributing to the heavy rain was the slowly swirling storm system itself, which was a relatively weak area of low pressure that succeeded in wringing the moisture out of the atmosphere like a wet sponge.

The storm — which dumped rain on the region from 6 a.m. Tuesday to 9 a.m. Monday — had tropical characteristics, with a warm air mass located near the center. Day after day, massive thunderstorms erupted around the storm's center, dumping rains over the same water-logged region.

Some spots picked up more than a foot of rain in 24 hours and 2 feet in 72 hours, an indication of the extreme efficiency with which the storm was converting water vapor in the air into rainfall.

Such "warm core" systems are generally known to be more efficient rain producers than typical cold-core systems.

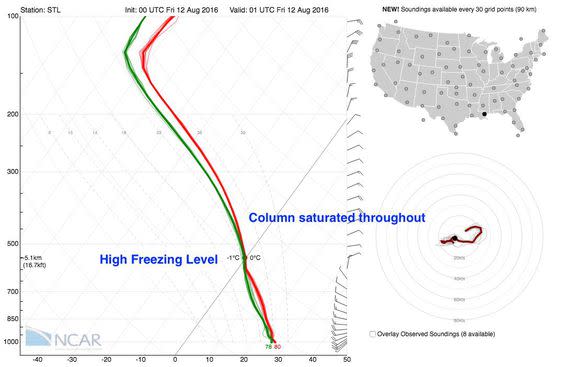

For example, a computer model and a sample of the atmosphere provided by a weather balloon in Louisiana on Saturday showed the freezing level was unusually high, at 17,000 feet, meaning that warm rain processes were taking place in much of the cloud layers.

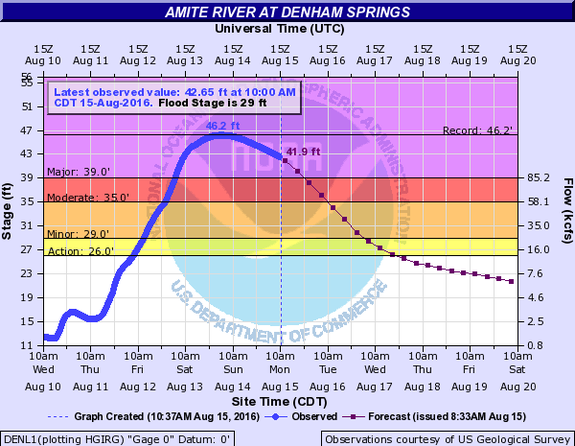

The rainfall totals that resulted from this storm are extraordinary, and they caused record crests on nearly a dozen rivers. In some cases, the rivers beat their previous record crests by several feet, rather than inches.

Image: NCAR

For example, the Amite River at Denham Springs, just east of Baton Rouge, hit 46.2 feet on Sunday morning, which was about five feet above its previous record crest in 1983. Records there date back to 1921.

According to the National Weather Service, The frequency intervals of this rainfall event show that this was about a 500-year event.

This doesn't mean that there will only be one such deluge every 500 years, though. Rather, it means that in any given year, there is a 0.2 percent chance of such rainfall occurring.

Here are some of the most impressive rainfall totals from this event:

Watson, Louisiana: 31.39 inches

Brownfields, Louisiana: 27.47 inches

Monticello, Louisiana: 26.26 inches

Lafayette, Louisiana: 21.60 inches

Baton Rouge, Louisiana: 19.14 inches

Gloster, Mississippi: 22.84 inches.

Climate change's role

If such rainstorms seem familiar to you, that's because they've been in the news more frequently lately.

According to Steve Bowen, a meteorologist for the insurance company Aon Benfield, there have been nine 1-in-1,000-year rainfall events in the U.S. since 2010 alone, including a deadly flooding event in West Virginia in June and a devastating flash flood in Ellicott City, Maryland in late July.

In general, this is the type of event that we expect to see occur more frequently, and with greater severity, as the climate continues to warm and more moisture is added to the air.

The record-high amounts of precipitable water and tremendous rainfall rates are suspicious, as well as the fact that this same area had 500-to-1,000-year rainfall events earlier this year.

Image: NOAA

Kevin Trenberth, a senior researcher with the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado, says he has not conducted an in-depth examination of this particular event, however:

"... Increasingly, these kinds of events are clearly enhanced by warmer temperatures and the ability of the atmosphere to hold more moisture at higher temperatures," he wrote in an email to Mashable.

Image: Weatherbell analytics

"The high temperatures themselves have a foundation of higher upper ocean heat content and associated higher sea surface temperatures. So there is a clear human component in them."

Trenberth said media reports that don't mention climate change in stories about these floods are "pathetic," given that the atmosphere can hold 7 percent more moisture for every degree Celsius of temperature increase. The actual percentage increase in precipitation during storm events can be much greater than 7 percent, however.

Image: Max Becherer/AP

Marshall Shepherd, a professor at the University of Georgia, said this flood fits a pattern he and a research team developed that found a tie between urban flood events and high amounts of precipitable water in the atmosphere.

"In a recent study we published in the Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology, we found that most urban flood events over the past 40 years exhibit top percentile precipitable water values," he said in an email.

"... The flood event in Louisiana fits the prototype very well," he said, speaking of floods resulting from "tropical-like” air masses.

Shepherd emphasized that there are non-climate change-related trends that make floods like this more likely, too.

Image: NCAR

"Days of tropical-like rainfall, saturated soil, lots of rivers and low-lying wetlands coupled with increasing urban impervious surfaces was the recipe for this type of event and I believe we will continue to see more of these 'new normal events' going forward."

Victor Murphy, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service, said Texas and Louisiana have been hit with at least six separate 500-year rainfall events since October 2015.

"The increase in water vapor in the atmosphere as the atmosphere warms is clearly a factor in priming the pumps for these extreme rainfall events," he said in an email to Mashable, noting that it's not clear exactly how much of a factor this is.

A recent report from the National Academies of Sciences found that studies do show "strong support for upward trends in the intensity and frequency of extreme precipitation events." An EPA report updated this month found that nine of the top 10 years for extreme single-day precipitation events in the U.S. have occurred since 1990.

That report indicates that heat waves and cold snaps have clearer climate change ties than extreme precipitation events. However, the report also notes that events like what is still unfolding in Louisiana have some scientific backing for concluding that global warming is playing some role in producing them.

Meteorological debate

The Louisiana floods have generated some debate in the weather community, since the Weather Prediction Center in Maryland, which is responsible for flood forecasting, wrote that it described the storm as tropical in origin. However, the National Hurricane Center, which would have jurisdiction over a tropical system, was silent, and never declared it a tropical depression.

This may seem like an esoteric discussion, but settling it may be important if global warming helps spawn more hybrid storm systems that feed off of warmer than average waters and take on tropical characteristics even when they are over land.

It is also important because the public may respond more to warnings when storms are numbered, as tropical depressions are, or named, like more intense storms including tropical storms and hurricanes.

The lack of a storm name could have hindered efforts to call attention to the flood threat in Louisiana, despite the storm's clear tropical characteristics.