'You were absolutely on your own': How LADACIN changed lives of severely disabled people

LAKEWOOD - Sandy Witkowsky had a 2-year-old son with cerebral palsy and a lot of questions.

This was in 1969, and there were not many answers.

“You were absolutely on your own,” she said.

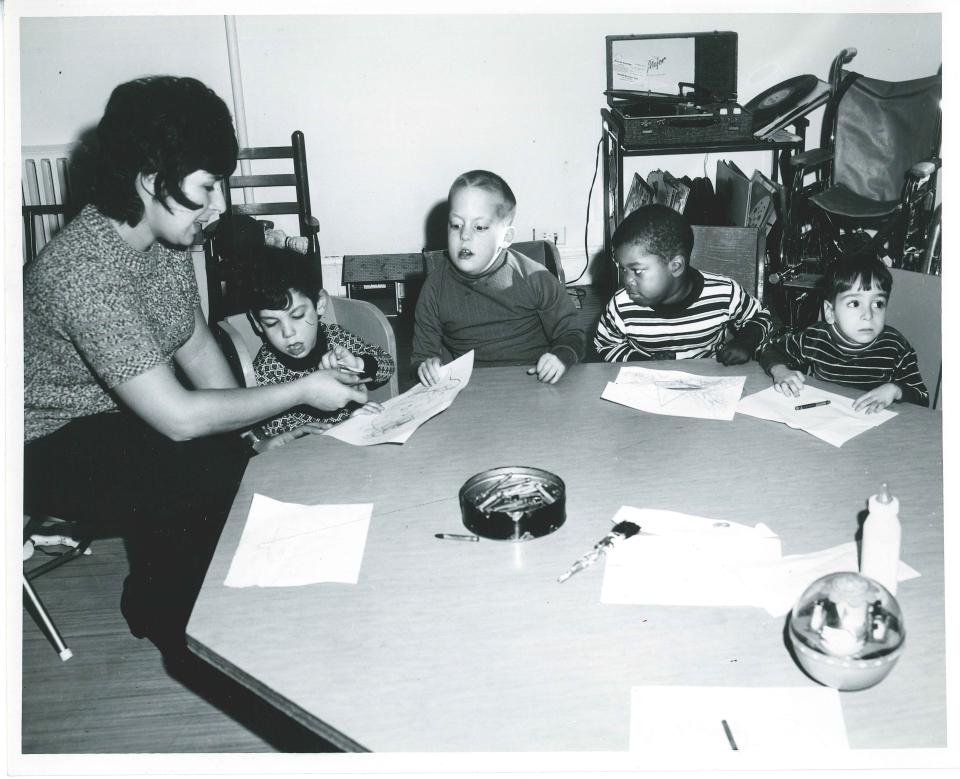

Eventually Witkowsky found one place that could help — United Cerebral Palsy of Monmouth and Ocean Counties, a school and treatment center in Long Branch. She started taking young David there three days a week, borrowing a station wagon to do it (accessible vans were a futuristic pipe dream).

Illness won't stop her: Multiple sclerosis knocked down Toms River woman; now she trains for her next triathlon

Before long it became clear that United Cerebral Palsy, well-meaning as it was, needed some financial help. So Witkowsky put up handmade signs in her local post office in Marlboro, looking to start a support group. Twenty people showed up to the first meeting.

Thus launched what became known as the “Marlboro auxiliary,” which would raise hundreds of thousands of dollars for the school through bake sales, bowling outings and the like over the next quarter-century.

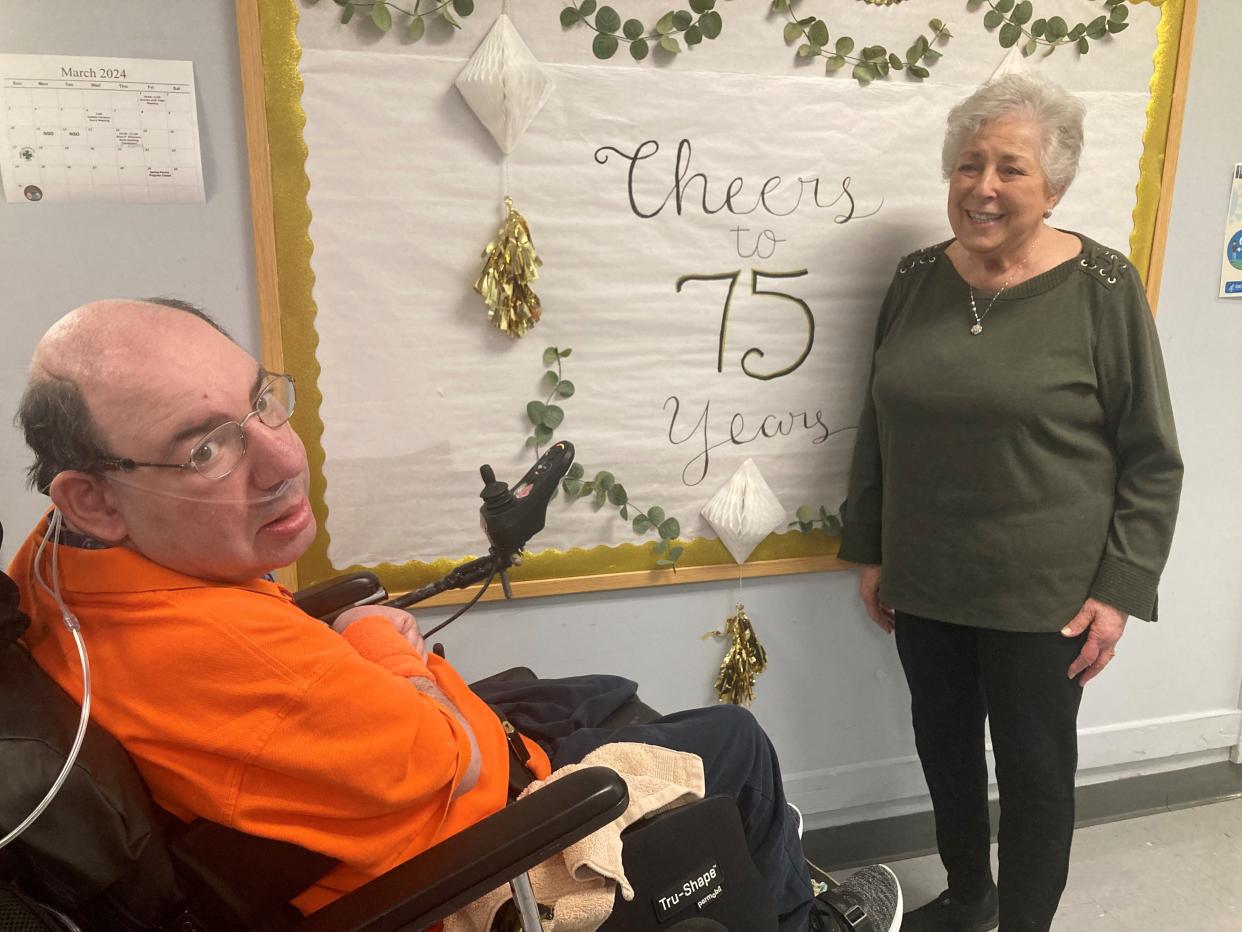

The effort bore fruit. Today United Cerebral Palsy is known as LADACIN Network, a nonprofit agency supporting children and adults with complex physical and developmental disabilities. (The name stands for Lifetime Assistance for Developmental and Challenging Individual Needs.) It has schools in Ocean Township and Lakewood and nine residential facilities. David, now 56, lives in one of them — and Sandy and husband Mark Witkowsky see him daily at the Lehmann School and Adult Day Program in Lakewood, across town from their home.

Night to Shine: Tim Tebow gala in Toms River includes people with disabilities in the fun

LADACIN turns 75 this spring, and on Saturday will hold an anniversary gala to recognize Sandy and others who helped elevate society’s care for the most disadvantaged among us.

“It’s amazing,” Sandy said of how LADACIN turned out. “It’s helped many, many people.”

Another pioneering family

In 1956 Janet and Emil Schroth started taking their young son, Em, from their home in Interlaken to United Cerebral Palsy.

“It was a dilapidated house that had a porch to it,” recalled Em’s sister, Missy Schroth Hislop. “I remember seeing small children in wheelchairs and walkers. That was it.”

'Show the world what you can do': Toms River woman with autism takes home pageant crown

Humble as it was, you have to remember the context of the era. There was no place else for those kids to go. “People were sent to institutions,” Hislop said.

Things didn’t just evolve by accident. It took people like Hislop’s father Emil Schroth, who became a major force behind United Cerebral Palsy.

“As my brother grew and his needs grew, I think that was a strong catalyst for LADACIN’s growth, too,” Hislop said. “It wasn’t just academics these kids needed. It was speech therapy, occupational therapy, physical therapy. Then it was (adult) programs.”

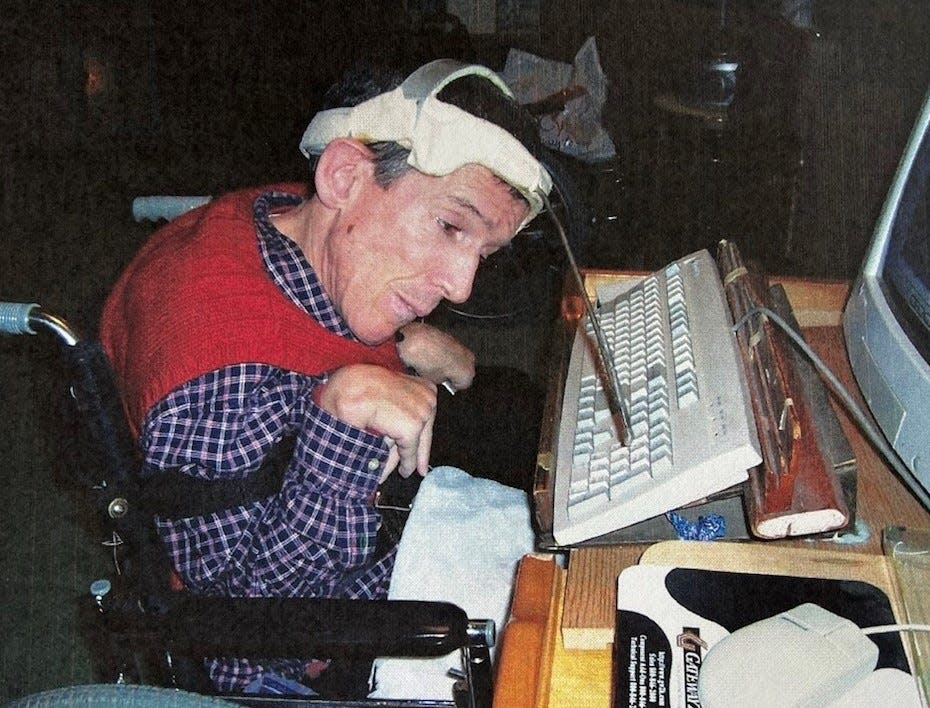

From humble beginnings at that rickety old house, LADACIN would advance to the point that, in the early 2000s, it helped equip Em Schroth with a cutting-edge means of communication.

“My brother had pretty good control over his head muscles, and he would use a head pointer,” Hislop said. “They found what he was good at, which was his head control, and they adapted this speech computer so he could operate it. I remember him ordering pizzas over the phone with it.”

Not sitting idle: Young adults with developmental disabilities find jobs at Kindness Cafe in Manasquan

Thanks to that ability to communicate, Em would give public presentations to raise awareness about cerebral palsy. He died in 2013 at age 58. LADACIN’s Schroth School and Adult Day Program is named after his family, which will be honored at Saturday's gala.

“Em was a bright light. He never had a bad day, and he was an advocate for people with disabilities,” Hislop said. “He wanted people to understand what it was like living with a disability, and at the end of the day how much he had in common with everybody else.”

'In our wildest dreams'

Over the years, Sandy Witkowsky filled a scrapbook with newspaper clippings, photos and fliers from her quest to raise money for United Cerebral Palsy.

“I look back and think, ‘Did I do all this?’” she said. “I guess I did.”

'I like working': Compassion Café on LBI offers jobs, meaning for people with disabilities

It enabled David to live the fullest possible life. His speech, though seemingly garbled to an outsider, is intelligible for those who know him. At his group home, he serves as an interpreter of sorts between the staff and less-communicative fellow residents.

When David was born, his father asked the doctor about his life expectancy. There was no answer.

“In our wildest dreams, we never would have thought he’d be this healthy and live all these years,” Mark Witkowsky said, crediting LADACIN’s support as they grew together. “After 75 years — miraculous.”

'Now there's a safety net': Marlboro mom's work pays off with autism driver's license law

Jerry Carino is community columnist for the Asbury Park Press, focusing on the Jersey Shore’s interesting people, inspiring stories and pressing issues. Contact him at jcarino@gannettnj.com.

This article originally appeared on Asbury Park Press: LADACIN celebrates 75 years bettering lives of disabled people