Violence, legal troubles and few consequences: Piecing together the life of Maxwell Anderson

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

As a teen, Maxwell Anderson skipped class and smoked inside his car, got caught at underage drinking parties and once called his dad as he ran from the cops.

In his early 20s, he routinely carried a gun and once confronted a roommate with it, worried about society collapsing and left “booby traps” around a shared house to thwart potential intruders, former roommates said.

In the ensuing years, Anderson was arrested in a series of domestic disputes with family members and was filmed punching a stranger who tried to intervene when he saw Anderson and a woman arguing.

Now, at 33, Anderson is accused of killing Sade Carleena Robinson, 19, after the two went on a first date. Prosecutors say Anderson dismembered her before trying to hide her remains in Lake Michigan and across the Milwaukee area.

The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel has interviewed multiple people who knew Anderson at different points in his life and reviewed records from courts and police agencies across Wisconsin.

What has emerged is a portrait of a young man who appeared to repeatedly flout the rules, faced few serious consequences and was prone to violence and alcohol-fueled rage.

Those who knew him as a teen described him as weird, awkward and spoiled, but added they did not believe then that he would be capable of what he is accused of now.

“Never in a million years did we think this was possible,” said one former friend, who asked not to be identified for privacy and safety reasons.

The Journal Sentinel interviewed five of Maxwell Anderson's former friends stretching from middle school into his early 20s, all of whom requested not to be identified publicly for privacy and safety reasons, given the serious allegations against Anderson and the media attention the case has received. The Journal Sentinel permits the use of anonymous sources in limited circumstances, and requires reporters to verify the source’s identity and to conduct additional reporting to corroborate what the source has said. All anonymous sources, including those used in this story, must be approved by a senior editor, who is provided the name of the source to verify it is a real person.

In response to questions for this story, Anderson’s father said he was “heartbroken” that his son has been charged “with such horrendous crimes.”

“As I said earlier, our family joins the Milwaukee community in mourning the horrific death of Sade Robinson. Our condolences to her family for their incomprehensible loss,” Steven Anderson said in a statement to the Journal Sentinel released through his son’s attorney.

Anderson acknowledged the severity of the allegations against his son, and said he and Anderson’s mother continue to love and support him.

“Being a parent isn’t always easy. Relationships can be complicated, complex and change shape over time,” he said. “But today, Max is still presumed innocent and we pray the public will not rush to judgment.”

The case has fueled outrage, fear and anger in Milwaukee with some, including Robinson's mother, comparing the situation to notorious serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer who was convicted in the 1990s of killing multiple young men of color and dismembering them.

The investigation into Robinson's death is ongoing. Officials have said there is no evidence suggesting there are other victims.

Milwaukee County Sheriff Denita Ball, whose agency is leading the probe, said last week authorities are working “to make sure we haven’t missed anything.”

“There’s nothing normal about this investigation,” she said.

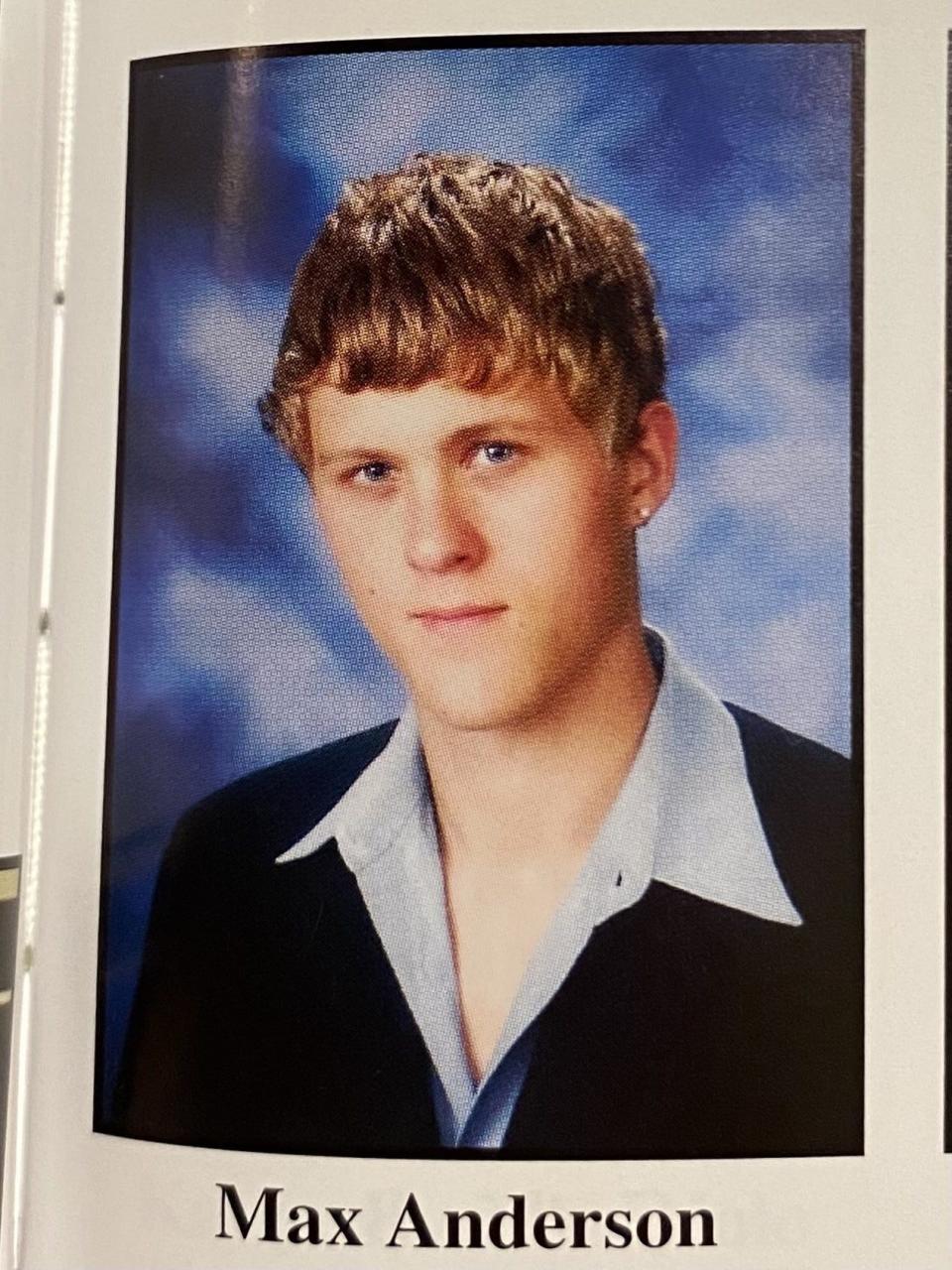

Anderson, known as ‘Archie,’ attended several high schools in Waukesha County

Anderson grew up in suburban Waukesha County.

He spent time at Kettle Moraine, Catholic Memorial and Pewaukee high schools, according to school yearbooks and one school spokesperson. He introduced himself as “Archie,” friends said, and spent at least one year on Kettle Moraine's wrestling team.

His family — Anderson has a younger sister — owned two homes when Anderson was a teen, one in a Delafield subdivision with an estimated market value of nearly $750,000, and the other on Pewaukee Lake with an estimated market value of $1.2 million, according to real-estate websites.

His parents filed for divorce in 2010, a year after Anderson finished high school.

Friends from this time recalled Anderson’s expensive clothes and that he always seemed to have cash. One said Anderson was sometimes bullied because of his clothes and physical appearance. All of those interviewed by the Journal Sentinel about Anderson’s early life made a point of saying he was a "weird" and "out there" teen.

Steve Anderson pushed back against the idea that he paid his son's way as he became an adult.

Although he helped his son buy a used car and a "modest home" in Milwaukee, "unconditional love has not meant unconditional financial support from his family," Steven Anderson said, adding his son "has in no way had a carefree lifestyle."

"Social media would have you believe that I have a habit of bailing him out of bad situations, but I can assure you that nothing could be further from the truth," his father told the Journal Sentinel.

"In the case of his past legal problems, when he’s done wrong, he’s had to accept personal responsibility for his actions. In his run-ins with the law, that has meant using a public defender or representing himself."

His son's legal trouble started early.

Records show multiple early interactions with suburban police agencies

Police in the Village of Pewaukee had repeated encounters with Anderson.

Several incidents occurred in January 2009, when Anderson was 18.

First, an officer spotted a car parked against traffic about 2:30 a.m. on New Year’s Day and noticed Anderson crouching behind the driver’s door. Anderson got in the car — his father’s — and fled, but stopped when the officer pulled him over. He admitted to having a beer earlier that night, records show.

Two weeks later, his school contacted police and asked that Anderson be cited for leaving class and smoking in his car in the school parking lot.

At the end of the month, Pewaukee police got an anonymous tip about an underage drinking party. The homeowner was out of town and said her niece was allowed to stay there. She gave the police the code to enter through her garage.

Officers found about 20 people in the basement. Anderson broke a basement window and ran away; other partygoers identified him as the person who fled.

That night officers went to Anderson’s house looking for him. Steven Anderson answered the door. He had last heard from his son after midnight, he said, adding his son told him he was sleeping over at a friend’s house. An officer handed him a business card.

“As we were leaving the residence, Steven advised us he would see us in court,” the report says.

Anderson showed up at the police station the next day. He said someone he didn’t know had opened the basement window and that he climbed through it.

He denied breaking the window and said he did not drink alcohol that night. He said as he ran away from the house that night, he had called his father who came and picked him up. Anderson received tickets for property damage and obstructing an officer.

Later that year, a Waukesha County sheriff’s deputy tried to pass Anderson while searching for a drunk woman who had waved a gun at a restaurant and fled in a pickup truck.

The deputy thought he had spotted the truck ahead and flashed his squad’s bright lights.

Instead of moving over, Anderson blocked the deputy from passing and flipped him off.

That night, after helping arrest the woman, the deputy called the listed owner of the vehicle, Anderson’s father. His father was “very unwilling” to provide any information and yelled at the deputy, who tried to explain the seriousness of the call he had been investigating, a report says.

Anderson later was sent two tickets in the mail.

Five months later, Anderson was again caught drinking at a house party. This time, he tried to hide behind an entertainment center, covering himself with a blanket.

As police led him out of the house, he was shouting obscenities, later apologizing to an officer for calling her a c--t, according to a police report. He was arrested and urinated in the squad car as he was taken to Waukesha County Jail.

Again, he received citations, not criminal charges, related to the incident.

A tense living situation in Arizona ends with a fight and a gun

Anderson graduated from Pewaukee High School in 2009.

Two years later, he was an active duty member of the U.S. Navy. His service ended just eight months later, though, according to records from the U.S. Department of Defense. The Journal Sentinel was unable to learn the circumstances of his departure.

Around that time, he reached out to a childhood friend from Waukesha County who had moved to Tempe, Arizona, for college. The friend had a spare room in his shared house. He invited Anderson to move in.

Two other people who lived in the house told the Journal Sentinel they thought their new roommate, who still went by "Archie," was “weird.”

They said he routinely carried a gun, usually in his pocket, and sometimes left it sitting out near him. The roommates also said Anderson made small "booby traps" around the house. He left marbles on the floor and whittled rabbit snares.

Once, he tried to suspend a wooden stake above the front door so it would fall on anyone who entered. The setup was "poorly designed," one of the roommates said.

Another roommate did not recall Anderson ever having a job or attending school during the time he lived with them.

Tensions grew inside the house, they said. Anderson never cleaned. If someone bought a pricier six-pack of beer, Anderson would drink it and then replace it with a cheaper brand.

He “wasn’t pulling his weight,” said the friend who had invited him to move in.

Eventually, that friend made plans to move. One night, the situation boiled over and the friend recalled telling Anderson he was selfish and a bad roommate. The friend went back to his room and sat at his desk.

Then Anderson came in — holding his gun, the friend said.

Anderson towered over his friend, using his free hand to push down on the desk chair.

He had been crying and did not look like himself, as if “someone else (was) in the driver’s seat,” the friend said.

He cannot recall exactly what Anderson said to him, only his sentiment, which was: I can’t believe you’re going to throw our friendship away.

The friend calmed Anderson down. He did not know if the gun was loaded and decided not to call the police. Another Arizona roommate interviewed by the Journal Sentinel did not witness the event but said he was told about it later.

The friend moved out of the house several months later.

He said he has not spoken to Anderson since.

Back in Wisconsin, violent episodes stack up

By July 2014, Anderson was back in Wisconsin and in trouble with the law.

During a visit that month, he began screaming and throwing things inside his mother’s house. A relative called 911 and deputies arrived to witness some of the altercation. In a report, a deputy described encountering Anderson, who said, “What are you gonna to do? Shoot me?”

Anderson then stole his mother's car, drove away and returned, crashing it into the house’s back deck, according to court records. His mother told authorities she believed he was under the influence of drugs or alcohol at the time. She did not want him cited or charged for property damage or stealing her car.

Another person at the house, believing Anderson was intoxicated, had tried to stop him from taking the car.

Anderson threw the man to the ground and got on top of him. Responding medical personnel said the man appeared to have several broken ribs as a result, court documents say. Anderson also was injured in the scuffle.

Anderson was arrested and charged with two counts of misdemeanor disorderly conduct, which together carried a maximum possible sentence of six months in jail and a $2,000 fine.

He pleaded guilty to one count in a plea deal and was ordered to pay $416 in fines and fees.

As the case went through the court system, Anderson changed his address from Boulder, Colorado, to an Oconomowoc house owned by his father.

Around this time, in September 2014, he messaged a former friend from Waukesha County. The friend showed the message to the Journal Sentinel. In it, Anderson said he had not "really kept in touch with anyone over the years I've been gone. Trying to reconnect with old friends."

The friend did not respond.

More court cases and plea deals in Door County and Milwaukee County

A year later, Anderson was staying with family in Egg Harbor, a village in touristy Door County.

His relatives had grown tired of Anderson not cleaning up after himself and tried talking to him about the problem, according to court records.

They also suggested he seek mental health treatment.

In response, Anderson threw a glass, punched a hole in the wall and smashed two phones when his relatives tried calling police, records show.

He was charged with disorderly conduct, two counts of criminal damage to property and felony witness intimidation. He entered into a plea agreement and the felony charge was amended to a misdemeanor.

Anderson almost didn’t take the deal because he did not want to serve any jail time, records show.

In all, he pleaded guilty to three misdemeanors – one criminal damage charge was dismissed – and was placed on probation for two years.

He was ordered to serve 10 days in jail with work-release privileges.

By 2019, his probation term was long over and he was in Milwaukee.

That year, he was charged with beating a 56-year-old stranger who tried to intervene when he saw Anderson and a woman arguing on West Wisconsin Avenue.

Anderson admitted hitting the man but did not respond when asked why he did so, the complaint says.

A witness had recorded much of the assault on her cellphone.

The video showed Anderson on top of the man, punching him multiple times before dragging him to the edge of the property. The man had blood running down his face when police arrived.

The Journal Sentinel's attempts to interview the victim in the case were unsuccessful.

Anderson was charged with battery and disorderly conduct, both misdemeanors. Again, he entered into a plea agreement.

Anderson received one year of probation after pleading guilty to disorderly conduct.

He also was given the opportunity for his probation to end early, after four months.

Anderson was a fixture at local taverns and clubs, working behind the bar and as a security guard

Alcohol appeared to be a factor in many of Anderson’s legal troubles.

But that did not stop him from working at bars across the Milwaukee area.

One night in January 2022, he was heading home from a shift at Heart Breakers, a strip club where he worked as a bartender and security guard, when West Allis police stopped him, records show.

He had been driving 70 mph on South 92nd Street where the speed limit was 30 mph. Anderson denied drinking alcohol but later was found to have a blood-alcohol level of 0.12, according to a criminal complaint, more than the legal limit of 0.08 considered proof of intoxication.

He was charged with two misdemeanors related to drunken driving and pleaded guilty to one.

He received one year of probation — with five days to be served in the House of Corrections with work release privileges — and lost his driver’s license for that time.

At a probation review hearing last August, an agent told the judge Anderson had been testing positive for cocaine, marijuana and alcohol. The judge added “absolute sobriety” as a condition of his probation.

Throughout this time, Anderson lived in a brick duplex on Milwaukee’s south side, valued at about $300,000, according to real-estate websites. The property was once owned by his father, who then sold it to him. Available records show police responded once to the address in recent years for a vehicle theft report; a records request to Milwaukee police for any reports related to Anderson remains pending.

Anderson also continued to work at clubs and bars, including The Rave and Victor’s Nightclub.

Daniel Narvaez, who regularly performed at Victor’s as DJ Wicked, was stunned at news of Anderson’s recent arrest.

“There was no red flags at all, at least, to the person that he represented himself as to me to be,” he told the Journal Sentinel. “He seemed like a bartender that generally likes to have fun and just do his job.”

Later in the conversation, he reflected: “You don’t ever really know people’s real intentions until you’re behind closed doors.”

Sade Robinson was MATC student, beloved by her family

A month ago, Anderson apparently crossed paths with Robinson, a 19-year-old criminal justice student at Milwaukee Area Technical College.

Robinson had grown up splitting time between Milwaukee and Florida, where her father lives. By late 2019, she was living full-time in Milwaukee with her mother.

She was beloved at her job at Pizza Shuttle on the city’s east side and close with her mother and sister.

"Anybody who knew Sade, knew that she was different from everybody else," her sister, Adrianna Reams, said at a vigil last month.

"Everything she had, she had by herself," Reams said, adding: "She went through a lot, but she never let that break her. She was the strongest person I know. She was the most beautiful person I know. She never deserved this."

On April 1, Robinson met Anderson for a date, according to prosecutors.

The next day, she was reported missing and a severed leg was found along the shores of Lake Michigan in Cudahy.

Later that week, investigators descended on Anderson’s home, carting out boxes of evidence, and arrested the 33-year-old nearby during a traffic stop.

His family retained Anthony Cotton, a Waukesha-based criminal defense attorney whose profile rose a decade ago when he represented one of the girls charged in the so-called Slenderman stabbings.

In the years since Cotton has earned a reputation as a formidable defense attorney. His website touts his skill at getting “confessions and other physical evidence suppressed” and says “he has won trials and beat cases that seem impossible to defend.”

Cotton declined to comment for this story. In the statement to the Journal Sentinel, Anderson's father said although he had not helped his son before in past legal matters, in this situation "the consequences of a mistake in justice would mean his loss of freedom."

"I love my son unconditionally, and that means I am helping him defend himself and making sure he has a good attorney to present his defense," he said.

After Anderson was jailed, authorities continued to collect surveillance footage, witness statements and phone records to piece together the movements of Anderson, Robinson, her phone and her car over the night she disappeared.

As prosecutors asked for more time — and more body parts were discovered — some in law enforcement feared Anderson would post his then-$50,000 bail and flee.

Days later, on April 12, Anderson was charged with first-degree intentional homicide, mutilating a corpse and arson in Robinson’s death. His bail was raised to $5 million.

This time, if convicted, he faces a mandatory life sentence.

Sophie Carson, Drake Bentley, Alec Johnson, Hannah Kirby and David Clarey of the Journal Sentinel staff contributed to this report.

Ashley Luthern can be reached at ashley.luthern@jrn.com. Contact Elliot Hughes at elliot.hughes@jrn.com or 414-704-8958. Follow him on Twitter @elliothughes12.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Maxwell Anderson: A life of violence, legal trouble, few consequences