Ventura County is safer than in decades, though crime fears remain

Jose Rivera grew up in Oxnard’s Colonia neighborhood, a teenager in the late 1970s and early 1980s. At the time, the nation was in a decades-long crime wave that would last into the 1990s. In La Colonia, there were killings every year, Rivera said, most of them gang-related. Twice, bodies were found outside his family home.

“In those days, people would rarely call the police,” he said. “They were afraid. A lot of the crime, especially in those small, close-knit communities, was committed by gang members and those folks had to live amongst those gang members, so there was a lot of fear of retaliation.”

Today, Rivera is an assistant sheriff, one of the top executives in the Ventura County Sheriff’s Office. His mother still lives in La Colonia, in the house where he grew up. The family long ago stopped trying to convince her to leave. These days, the community doesn’t live in fear anymore.

In 2023, Oxnard had seven murders and other criminal homicides, according to data released recently by the Oxnard Police Department. That was the fewest since 2001, when the city had six. As recently as 2019, Oxnard reported 14 criminal homicides, twice as many as last year.

Both violent crimes and property crimes are much rarer than they were a generation or two ago in Oxnard, in Ventura County as a whole and in the entire nation. Ventura County’s murder rate was about twice as high in the early 1990s as it has been for most of the past decade, according to statistics kept by the California Department of Justice.

Property crimes were far more common in the past, too, even the recent past: In 2013, for example, there were about twice as many burglaries in Ventura County as there were in 2022. Go back another 20 years, to the early 1990s, and the per-capita burglary rate was about five times what was it was in 2022.

'Very frustrating' to compare crime rates with new data method

Those countywide statistics only run through 2022 because the California Department of Justice doesn’t plan to release county-level crime stats for 2023 until July.

Over the past few months, police agencies in Ventura County have released their own statistics for 2023. According to those reports, criminal homicides in Ventura County ticked up last year, from 18 in 2022 to 21 in 2023, but remain at some of their lowest rates of the past 40 years. Criminal homicides include both murders and other unlawful killings, such as manslaughter, but not those made in legal self-defense.

Nationwide, homicides were down 13% from the fourth quarter of 2022 to the same period of 2023, after rising during the early years of the pandemic, and all violent crime was down about 6%, according to statistics released by the FBI.

Most police agencies in Ventura County reported declines in both violent crime and property crime for 2023. There were exceptions: In the areas patrolled by the sheriff's office, property crime was down in 2023 but violent crime was up, driven largely by a more than 100% increase in aggravated assaults.

"There were significant increases in firearm-related aggravated assaults and much of the increase was related to brandishing of firearms to multiple victims," Sheriff Jim Fryhoff said in a statement his office released along with its crime statistics. If someone brandishes a gun at multiple people, it is considered a separate crime for each victim.

But it’s tough to tell whether crime in general was up or down in 2023 in Ventura County, or in most of its biggest cities, because the county is in the middle of a shift in how it measures and reports crime.

For nearly a century, police agencies in the United States have made annual reports to the federal government on the number and types of crimes in their jurisdiction, something known as Unified Crime Reporting. In 1989, the FBI unveiled the National Incident-Based Reporting System, or NIBRS, which provides more detail and includes more types of crimes.

Police departments have been making a slow transition to NIBRS, with the FBI switching to the new system for national data collection in 2021. Today, about 80% of police agencies in the U.S. use NIBRS, according to the FBI.

But half of Ventura County was still on the old system last year. The county has six police agencies: the city police departments in Oxnard, Ventura, Simi Valley, Santa Paula and Port Hueneme, and the sheriff’s office, which covers the other five cities and the unincorporated areas.

The Oxnard, Ventura and Simi Valley police departments all started using NIBRS at the start of 2023. The sheriff’s office and the smaller police departments in the county made the switch this year, so their 2023 crime stats still used the old system.

Vickie Jensen, a professor and chair of the Department of Criminology and Justice Studies at CSU Northridge, said that the new system “is different enough that I think you have to be very cautious” when comparing a city’s stats before and after it adopts NIBRS, or between cities that use NIBRS and those that don’t.

“It’s very frustrating to try to establish comparisons,” said Oxnard Police Chief Jason Benites. “The magic question is always, how does it compare to the previous year? And the easy answer this year is, they’re very different and they can’t really be compared.”

The biggest difference might be in how much more detail is collected with the new reporting system, and how many more crimes it measures.

Before NIBRS, if an incident involved more than one crime, only the most serious crime was included in the statistics. For example, if someone robbed a person and then killed them, it would be reported as only a homicide.

With NIBRS, each of those crimes is captured in the data. That means departments that switch to NIBRS will often report higher levels of crime, even if the only thing that changed in their cities was the way they count the crimes.

The new system also includes more demographic information about suspects and victims, and more information about the circumstances of a crime, such as whether the victim and perpetrator knew each other.

“From a researcher’s perspective, NIBRS is potentially amazing,” Jensen said. “There are an infinite number of variables than can be examined. It just opens the door wide open.”

How Ventura County got safer

Long before police in Ventura County adopted the newer, more sophisticated method of tracking crime, it was clear that the streets had become safer. Ventura County’s per capita rate of combined violent and property crimes in 2022 was less than half of what it had been in 1996, and about 30% lower than it had been in 2016.

In 2022, Ventura County had the lowest violent and property crime rates of any of California’s 16 largest counties, according to data from the state compiled by the Ventura County Civic Alliance in its 2023 State of the Region report.

The long-term trend mirrors the decline in crime nationwide in the 1990s, though Ventura County continued to get safer in the 2010s when crime in most of the country had plateaued.

There are a variety of theories as to why crime rose so much from the 1970s into the 1990s and why it declined so quickly afterward — from the economy to the levels of lead in paint and gasoline — and no answers that are universally accepted among experts.

In Ventura County, particularly in Ventura, Oxnard and Port Hueneme, street gangs are less visible than they were in the 1990s and early 2000s. Gangs still exist and their members still commit crimes, but much of that activity has been pushed out of sight — or onto the internet, where gangs often have a social media presence.

“In my early days in this department, the gang activity was very overt,” said Benites, who joined the Oxnard Police Department in 1993. “It would not be out of the ordinary to go through the Colonia neighborhood and see gang members dressed in gang attire in different locations, engaged in drug dealing and other criminal activity."

It's less overt, and gang members aren’t as obvious, he said.

"That doesn’t make them any less dangerous, but it’s less visible to our residents and being less visible probably reduces the level of violence and fear in the community,” Benites said.

From 2004 to 2006, the Ventura County District Attorney’s Office obtained civil injunctions against Oxnard’s biggest street gangs. The injunctions allowed police to arrest anyone in certain areas of Oxnard and Port Hueneme if they had been identified as gang members and if they violated the court orders, which could include being out late at night, wearing gang attire or hanging around other gang members.

The injunctions were challenged in court by people who said they were never given a fair chance to contest their alleged gang membership. Police stopped enforcing Oxnard’s gang injunctions in 2017, and a judge dissolved them in 2021.

Twenty years after the first Oxnard gang injunction, there’s no consensus on what it accomplished, but it did coincide with a period of reduced gang activity.

Oxnard Mayor John Zaragoza, who was a city council member when the injunctions started, said he thinks they helped to reduce crime. But just as important, he said, was a move toward community policing that started in the 1990s, when the Oxnard Police Department opened a storefront station in La Colonia.

“Instead of having cops driving around, they walked the neighborhood,” Zaragoza said. “That really helped a lot. Those interactions between the kids and the cops were really great.”

Zaragoza and Benites also both pointed to the crime-suppressing effects of youth programs like the boxing gym run by the Police Activities League, and the teen centers run by the Boys & Girls Clubs of Oxnard and Port Hueneme.

“Police and law enforcement is just one spoke on the wheel of making neighborhoods safer,” Benites said. “Having neighborhood watches, active neighborhood councils, community-based organizations that interact with our youth, after school programs — it’s a collection of efforts that make communities safer.”

'You don't want to end up like that'

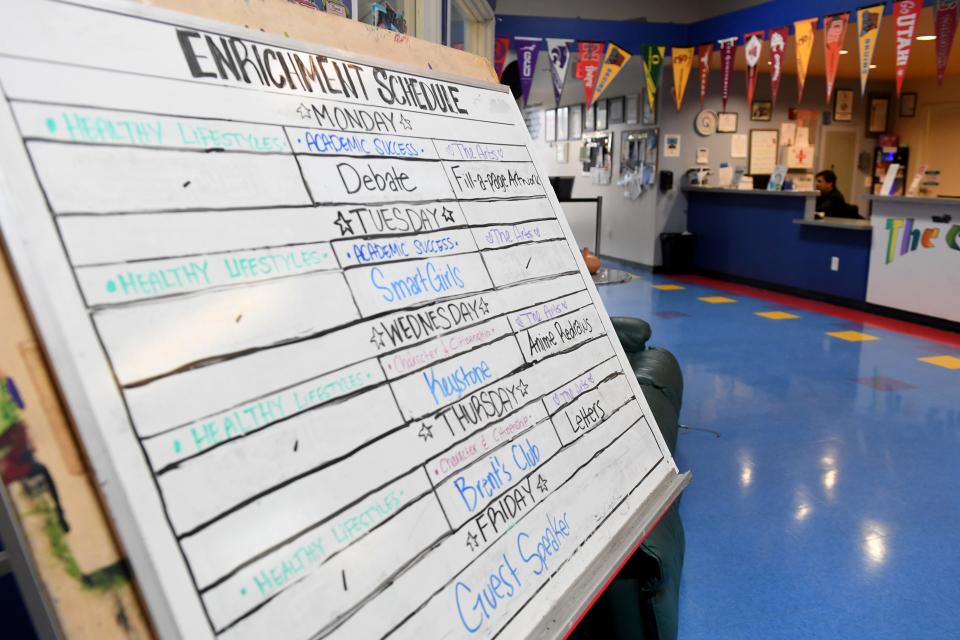

On a recent Monday afternoon, about a dozen teenagers congregated at the downtown Oxnard Boys & Girls Club teen center. A few of them gathered quietly in one room to work on their art projects, while a larger, louder group practiced its debating skills by researching whether dogs or cats make better pets.

Moises Salceda was on Team Cat. An 18-year-old high school senior, he credits the teen center with setting him on the right path in life.

He didn’t choose to start attending — it was a condition of his probation, after he was convicted of a misdemeanor and spent a few months in the Ventura County Juvenile Justice Center for his part in a major brawl at Pacifica High School three years ago. But he’s no longer on probation, and he still shows up almost every day.

“If I wasn’t here, I’d be going to houses I shouldn’t be going to, hanging out with the wrong crowd on the streets,” he said of the Boys & Girls Club.

Salceda grew up in Oxnard, near the Colonia neighborhood. One of his older brothers was involved in a gang, and Moises was drinking and smoking weed by the time he was 10 or 11 years old. When he was 15, a close friend was shot and killed.

“I was very close to him. We grew up together,” Salceda said. “I keep that with me as motivation to turn my life around. You don’t want to end up like that.”

His family now lives in Camarillo, and he’s attending Newbury Park High School. He’s on track to graduate next month and plans to enroll in a welding program at Oxnard College. At the teen center, he learned how to write a resume, and last summer he had a job at a grocery store.

“Now, I have to go out in the real world and use what I’ve prepared for here,” he said. “I’ve put myself in a good situation by coming here.”

Salceda has seen his share of violence in Oxnard, but he said that his impression from talking to his parents and older siblings is that it used to be worse.

One way in which things used to be different is that there used to be a lot more kids like him, with criminal records and time spent incarcerated. Arrests of people under the age of 18 in Ventura County dropped by 81% between 2008 and 2022, according to data from the California Department of Justice.

And when a child is arrested, probation is much more likely than incarceration. The Ventura County Juvenile Justice Center opened in 2003, built to house up to 420 people. It usually held about 200 back then, and these days, it has about 60 residents.

“There are community alternatives to incarceration, and the Boys & Girls Club is one of them,” said Erin Antrim, the CEO of the Boys & Girls Clubs of Oxnard and Port Hueneme. “They learn arts, they learn music, they have positive peer associations, and that changes these kids’ trajectory.”

Business owner who's been a break-in target: 'It's scary'

Though the data doesn’t support the notion of a pandemic-era crime wave in Ventura County, certain crimes, such as shoplifting and commercial burglaries, loom larger in the public imagination than ever before.

Ventura Police Chief Darin Schindler thinks that when it comes to shoplifting and petty theft, the statistics aren’t keeping up with reality, because businesses aren’t reporting those crimes anymore.

Schindler said major retail chains like Target and Walmart now have policies against calling the police on shoplifters. Instead, if a store catches someone stealing, they will agree not to press charges if the person agrees to pay a financial settlement.

Commercial burglaries — break-ins at stores and other businesses — are another example of a crime that has grabbed the public’s attention, even if the statistics don’t show that it’s more common than it used to be.

Certain types of businesses are targeted more than ever. Pharmacies are a prime example, Schindler said. In recent months, a number of pharmacies in Ventura County have been hit by thieves who break in in the middle of the night, grab pills and other high-value items, and get out quickly. In Ventura, officers on duty at night are now told to do some of their paperwork in a pharmacy parking lot, to deter would-be burglars.

Smoke shops and liquor stores also appear to be common targets.

George Touma and his family have owned smoke shops in Ventura County for the past 14 years, and for about 10 years before that, they owned liquor stores and dollar stores. Before the pandemic, crime was never really an issue; of the family’s nine smoke shops, one of them would be broken into every few years.

In 2022, something changed. One store, House of Smokes in downtown Ventura, was broken into three times between December 2022 and the summer of 2023. The family’s stores in Camarillo and Simi Valley have also been hit repeatedly, Touma said. Things have calmed down so far this year, but he doesn’t feel much better.

“The rate at which it’s escalated in the past couple of years has been outrageous,” he said.

Security cameras have captured the break-ins, and they all follow the same pattern, Touma said. The crew comes at around 3 a.m., usually in two cars, one of them circling the block as a lookout. A group of four or five men, with their faces, arms and hands fully covered, break a glass door and cut through a security gate. They go straight for the cigarettes and take every box they can, and within two or three minutes, they’re gone.

“This is organized crime,” Touma said. “They’re very professional.”

Cigarettes are high-value and easy to sell on the black market. The first time Touma’s downtown Ventura shop was hit, the thieves took about $25,000 worth of cigarettes from the shelves and a storeroom in back. They also took a locked safe.

After that, Touma and his family hardened their security. The store now has three-fourths inch-thick glass on the doors and windows and roll-down security gates. The back room has a metal door, and the safe has been secured. The alarm now goes off outside the store as well as inside.

“We’re trying to delay their entrance as much as we can,” Touma said. “If we can delay them maybe 15 minutes from getting in back, then usually, if they’re quick, the police will get here in 15 minutes.”

Touma said the total cost of the three burglaries at just the downtown Ventura store was about $100,000, including losses and the price of beefing up the security. Insurance only covered the first $10,000 of losses in each calendar year.

“That’s major losses. We don’t even make that much profit in a year,” he said. “It’s scary, what we’re seeing. Small business owners are closing their businesses almost on a daily basis, and it’s because of stuff like this.”

Tony Biasotti is an investigative and watchdog reporter for the Ventura County Star. Reach him at tbiasotti@vcstar.com. This story was made possible by a grant from the Ventura County Community Foundation's Fund to Support Local Journalism.

This article originally appeared on Ventura County Star: Ventura County is safer than in decades, though crime fears remain