'Utter turmoil': Former National Guardsman reflects on Kent State tragedy of May 4, 1970

Editor’s note: The author of this personal recollection was an Ohio National Guardsman at Kent State University on May 4, 1970. He has requested that his name not be published to protect his identity.

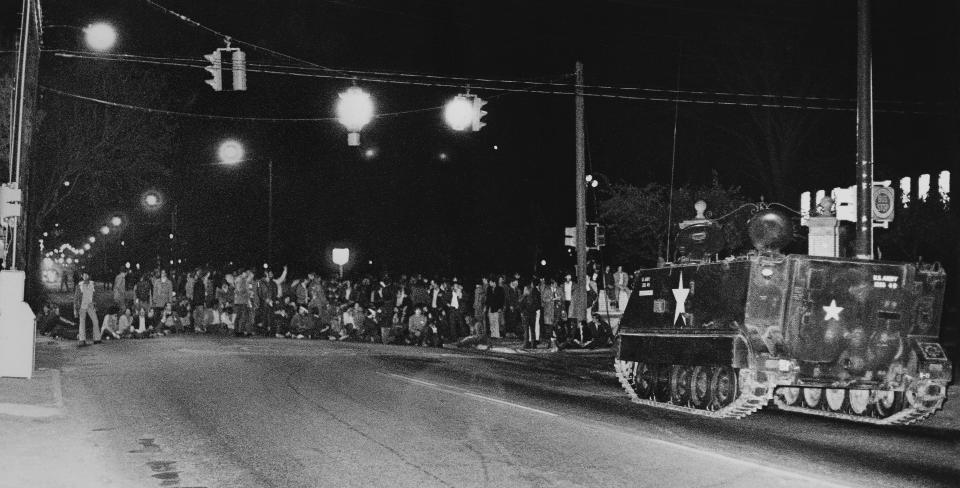

This dramatic photograph encapsulates the tragedy of May 4, 1970, when Ohio National Guardsman killed four students and wounded nine others during a Vietnam War protest at Kent State University.

When people see John Filo’s Pulitzer-winning photo of a girl kneeling over the body of a protester, they may have totally negative feelings of the Guard. They may feel that the troops acted with malice or that they acted without cause or perhaps even worse.

As with any photograph, this picture reveals only a split-second moment in time, but shows nothing of the preceding hostilities and confrontations that occurred between the Guard and demonstrators.

With that in mind, it would be an injustice to the National Guard and history not to consider more of the facts and circumstances that led to this unforgettable tragedy.

At the time, I was serving in Company C, 145th Infantry, out of Akron, and was a participant and observer of much of this chaos and turmoil. This is my account of what took place on the Kent State campus in May 1970.

Our company had been activated in late April, several days before our arrival in Kent, to assist local law enforcement officers who were protecting nonunion truckers driving in convoys along the Ohio Turnpike. Striking Teamsters had fired shots at the convoys. Our role was to assist in curtailing that activity and we spent several days in Richfield, Ohio, on that assignment, and would spend an additional three days at Kent State.

SATURDAY, MAY 2

We packed our gear and relocated from Richfield to Kent. Rumors had spread that Vietnam War protesters planned to torch the Army ROTC building on campus. Demonstrations had erupted the previous night, Friday, May 1, in downtown Kent after President Richard M. Nixon announced on television that the U.S. military had crossed into Cambodia. We learned that Kent police were unable to control the crowd and restore order as vandals smashed windows on storefronts.

On Saturday evening as we convoyed along Route 59 past the campus, we saw the rumors were accurate. The sky was bright red from the reflection of flames as the ROTC building burned. It was an unbelievable sight, and became an ominous prelude to the confrontations to come.

SUNDAY, MAY 3

Early that morning, a number of troops were assigned to guard-duty posts. I was posted at the Kent State University Airport. Others were assigned to the campus where some Guardsmen were engaged in mostly good-natured conversations with students.

Some of us were college students ourselves, and a few were even enrolled at Kent State. And like many students, some of us shared concerns about the war in Vietnam. Regrettably, this amicable atmosphere would not continue over the tumultuous hours and days ahead.

Our officers received word that more fire bombings were anticipated that evening. In response, our company was assembled that afternoon with the majority of us deployed on campus. Our orders were to form an impenetrable line to block protesters from gaining access to the Air Force ROTC building along with the president’s house and old Rockwell Library. There were around 80 of us along this defensively formed line and we nervously anticipated what might take place.

At dusk, the Victory Bell began to ring, which was the signal for students to gather at the area known as the Commons.

Though not clearly visible to us, we could hear the crowd and several emotional speeches followed by loud chanting, and then significant yelling and screaming. Suddenly around 2,000 demonstrators came charging down the hill directly toward us.

As this energized crowd moved closer, it seemed to grasp the potentially physical encounter that might ensue, and when ordered to disperse and leave the area, they thankfully stopped short, but near our line.

We maintained that defensive position for close to an hour and prevented any access or damage to the Air Force building. A key note: Most of us were armed with an M-1 rifle (with eight rounds locked, not loaded, with safeties on), with bayonets affixed, and we wore gas masks.

After significant verbal abuse, threats and inappropriate taunting, the Guard fired a few gas canisters toward the crowd and the protesters finally ran off and proceeded to a grassy field next to the library. As they did so, we quickly “moved out,” and in an effort to arrive before them, took a more direct route to the same area.

A group of students attempted to block our path, which resulted in some brief but aggressive pushing and shoving, coupled with a few inflicted rifle butts, which effectively served to disperse them.

When arriving at the library, we reorganized and once again formed a line along the sidewalk that extended to Route 59. While moving into position, I was totally surprised (and hoped our captain wasn’t) to see a larger, more energized and hostile crowd in front of us!

It seems the demonstrators we had just confronted joined up with a larger body of dissenters who had been part of a nearby “sit-in” and were returning to campus.

By some estimates, there were over 3,500 students in this general area that night, with about 700 in our immediate vicinity. Not everyone in this crowd took part in the ensuing hostilities, but it was clear that a hard-core group of radical agitators was totally committed to that goal. Their efforts to recruit more to join them were relentless.

As the night wore on, this core group proved very successful in its quest as the number of participants increased dramatically and the altercations continued to unfold.

Some accounts of that Sunday night would suggest it was fairly uneventful and that not much “went down,” but as a participant in that hostile environment, I respectfully disagree. The next few hours intensified as the friction increased considerably between the crowd and the National Guard.

It was now virtually dark and the protesters were moving everywhere around the field and had managed to surround our formation to the front and rear. The crowd’s language was atrocious and became really annoying. Mostly we heard: “Hey, Pigs, get the f*** off our campus!” and “1, 2, 3, 4 … we don’t want your f***ing war!”

At this point, every other Guardsman was ordered to do an “about-face,” a maneuver that allowed us to observe only those we faced, but not those to our rear. We were continually informing the troops next to us what was going on behind them.

The core agitators continued jutting in and out of the crowd, doing their best to rally ever-more students to join the chaos. It was now totally dark, and as the crowd grew larger, it became noticeably more aggressive. Many of the participants were greatly aggravated, and appeared eager to rush forward and engage our formation even though our rifles, gas masks and affixed bayonets remained in clear view.

When it became apparent the demonstrators were not going to curtail their activities, orders were relayed by our officers (through bullhorns), as well as from the helicopter’s speaker above, that the participants were breaking the law and to disperse immediately! Not only did they refuse to leave, their numbers continued to increase and they became even more belligerent.

This protest had become an outright riot as the participants threw rocks, beer bottles and anything else they could lay their hands on, inflicting minor injuries on several of us. Guardsmen armed with an M-79 weapon fired tear gas canisters toward the crowd, and to our surprise, many were thrown back at us even though they were extremely hot!

The helicopters above began spraying additional tear gas while fanning their searchlights on the chaos below. Due to the darkness, poor visibility and searchlights beaming downward, the night began to resemble an eerie scene from a sci-fi movie.

The crowd moved closer with a few members charging our formation, resulting in injuries on both sides. Finally, after various attempts to negotiate an end to the night’s turmoil had failed, the demonstrators were warned that those remaining after 11 p.m. would be cleared from the area.

Some left, most did not. Shortly, we were ordered to “move out and clear the area.” Our efforts were aided by the amount of gas that remained in the air, plus the crowd finally seemed to be tiring after several hours of chaos. After the field was mostly cleared, we “escorted” the last few who remained to their dorms. The riotous behavior was subdued and further hostilities ended. At least until the next day: Monday, May 4!

When I think back of the strained atmosphere and tension that existed on campus that night, I thank God no one fired a shot. Given the close proximity of the crowd plus the darkness, the potential carnage that could have resulted would have been far worse than what took place the next day. I commend our captain for his leadership in restraining our company during this encounter, and averting that potential disaster.

Of further significance, Gov. James A. Rhodes, Kent Mayor LeRoy Satrom and others from the university and National Guard had met Sunday morning in Kent to determine whether to shut down the campus.

When considering what had already transpired (particularly the torching of the Army ROTC building), and that yet another protest was planned the next day, some of us felt certain the university would be shut down. Unfortunately, it wasn’t.

MONDAY, MAY 4

Late that morning, Guardsmen from A & C Companies, 145th Infantry, and G Troop, 107th Cavalry, returned to campus. A total of 113 troops formed a skirmish line in front of the burned-out ROTC building.

An estimated 4,000 students were scattered around the Commons, with the largest concentration of about 800 gathered around the Victory Bell, which rang incessantly throughout this day’s ordeal.

The energized crowd was told numerous times to disperse immediately and leave the area. As before, the protesters defied those orders. Tensions were high as the troops moved into position that morning. It would intensify as the day’s confrontations escalated.

Around noon, the Guard fired gas canisters in an effort to move the gathering. The troops were then ordered to “move out and disperse this crowd!”

On edge and apprehensive of what the crowd might do next, the troops moved out. The men from C Company marched up the Commons to the left and formed a line next to Taylor Hall with orders to assist with crowd control.

The larger body of troops from the 107th and A Company veered right and moved up the Commons to disperse the concentration of students located near the Victory Bell. As was the case Sunday night, much cursing, taunting and rock throwing was directed at those men.

When the unit reached the crest of the hill, it stopped. Not only were the Guardsmen confronted by the dissenters they had just scattered, but also by many more students located over a large, open area below. After a brief pause, they proceeded to disperse this now reorganizing crowd.

When their formation marched down the hill toward a large field, they inadvertently maneuvered themselves into a fence line that would require them to do an “about-face” and return back up the hill they had just descended.

At this point, the crowd was somewhat scattered and quieted, but as the protesters realized the Guard’s dilemma, they seemed to become even more energized than before, moving closer, cursing louder, throwing more rocks and returning our fired gas canisters.

A number of troops inexplicably knelt and took a “firing” position directed at the crowd. After a brief and tense standoff, the troops regrouped, turned and marched back up the hill. As they moved out, the reenergized crowd followed.

The pace quickened as the protesters pressured the Guardsmen. When the troops reached the crest of the hill, some looked back through their gas masks, which may have caused the protesters to appear closer than they actually were.

At this point, more troops turned, took a firing position and raised their rifles. I distinctly heard one shot fired; then all hell broke loose when 28 men fired a total of 67 shots over a period of 13 seconds. The devastating result was that four students lay dead, and nine others were wounded!

When the firing began, the students were mostly centered on the parking lot and field below, and erupted into a state of confusion, scattering every which way while trying to find cover.

As the firing ceased, the students grew momentarily quiet; but as they grasped what had just happened, they started running around screaming uncontrollably at everyone and everything, and yet at nothing at all. Their frenzied state finally subsided and they began to disperse. In short order, ambulances arrived and medical personnel tended to the casualties. It was a horrendous sight and anyone who witnessed it, whether actively involved or a bystander, would not ever forget.

The Guard returned to the burned-out ROTC building but remained on “full alert” as a large group of students once again gathered on the Commons. Many were so frenzied they seemed determined to charge at the Guardsmen, which would have resulted in an absolute massacre.

Thankfully, further violence was averted when a few faculty members stepped in to persuade the students to leave the area, which they finally did.

Slowly the campus quieted and a large number of Ohio state police marched onto campus to establish order. The altercations and riotous activity ended and the KSU campus finally shut down.

During the days that followed, all students and National Guardsmen vacated the campus. With the hostility, aggressive behavior and stressful altercations we dealt with during those frantic days, I will remember them as some of the most anxious experiences of my life.

Like many other Guardsmen, it was not my choice to be on the Kent State campus “mixing it up” with protesters, but those were our orders and they were not optional.

There has been significant debate as to why the troops opened fire on the crowd that day. During the course of many investigations and court cases, the Guard’s official position was that the troops “believed they were being overrun by the hostile crowd and thought their lives were endangered.” In a federal court in 1975, the National Guardsmen were found “not responsible” for their actions.

In closing, I’ve added a few key factors for readers to consider in forming their conclusions and opinions as to why this clash ended so tragically.

An increasingly larger number of students had been radicalized by recent campus rallies, speeches and meetings held by revolutionary groups such as the Students for a Democratic Society, the Weathermen, Jerry Rubin and others. Some still believe these radical groups helped to organize the protests that took place.

The Guard’s presence was clearly unwelcomed by the students and their hostility appeared to intensify as the conflict wore on. Through all the confrontations, we were mostly on the defensive, not knowing what the crowd would do next, and after hours of vicious threats and assaults, we became disgusted with the never-ending unruly behavior and pressure, and our nerves became frayed and exhausted.

Most students did not believe our weapons were loaded, and those that did thought our ammunition was simply blanks, even though they were repeatedly and loudly told otherwise. (If the students had only listened to what they were told, it may have tempered their actions). The Guard’s weaponry used during this conflict was also a point of contention. This issue was addressed, changes were implemented, and we began training with less lethal crowd-control weaponry and equipment.

I recollect the masks we wore were beneficial in reducing the sting from the tear gas. They became hot and sticky, and made breathing difficult (particularly when humping up and down hills). It was also possible that these masks served to distort the troops’ perceptions of the crowd’s proximity and movements.

The debate continues whether the troops had “orders to fire.” I was not part of that unit so I do not know the answer. The only order our unit received was very explicit and simple: “Restore order and prevent further property damage.” Dealing with the crowd’s aggressive behavior was most stressful, but even with that, I find it hard to believe there was any intention to end this conflict as it so abruptly did.

I began this essay by noting the May 4, 1970, photo reflects only the dramatic outcome of this historical event, but does not give the viewer the “whole story” of what occurred at Kent State. My intention in presenting this narrative was not to justify the Guard’s actions or to fault them, but rather to give the reader a clearer perspective of what transpired by providing further insight into the utter turmoil, chaos and hostility that led to this tragic conclusion.

Respectfully submitted,

A former National Guardsman

This article originally appeared on Akron Beacon Journal: Former National Guardsman recalls Kent State tragedy of May 4, 1970