‘It has all of us shaken.’ Former MO boarding school students call bill political ploy

For a few hours Tuesday, after a Missouri House committee passed a contentious boarding school bill, dozens of former students flooded Aralysa Baker’s phone with texts, messages and calls.

They were confused, she said, about what the bill would do and why lawmakers would take up a measure critics said could wipe out some good that’s been done to hold unlicensed boarding schools accountable.

“This is scary — it has all of us shaken,” said Baker, who from 2005 to 2007 attended Lighthouse Christian Academy, run by ABM Ministries, in southeast Missouri. “Every time that we get a glimmer of hope, it feels like it’s been snatched away by something along these lines, where there are lawmakers that are trying to undo everything that has been gained. It’s too much sometimes.”

The House Children and Families Committee passed House Bill 2307 by a 6-2 vote that could have eventually sent the bill to the floor for debate. Hours after the vote, however, committee chair Hannah Kelly, a Republican from Mountain Grove, told The Star in an email that the proposal wasn’t going anywhere. She did not answer a follow-up question about why it would not be advancing to the full House for debate.

Former students, child advocates and some lawmakers wonder why Kelly’s committee gave the bill a hearing at all if there were no plans to advance it.

“It’s my belief that the owners of these homes, as well as legislators, are completely dismissive of the devastating impact maneuvers such as these have upon older survivors,” said Emily Adams, a vocal advocate for boarding school abuse victims who drove from southwest Missouri to attend Tuesday’s hearing.

“Nightmares, flashbacks, panic attacks, uncontrollable crying and increased sensitivity to our CPTSD triggers. Do we not deserve better, considering what we endured as teens?”

Critics say they suspect the committee hearing and vote to pass the measure were only a political ploy to appease those who are pushing the bill — especially in an election year — with no consideration for how the action could affect and retraumatize former students. They worked alongside lawmakers for months in 2021 to pass House Bill 557, which placed some regulations on the religious-based schools.

The proposed legislation, critics further contend, could undermine the 2021 law meant to protect kids by requiring unlicensed schools to register with the state, conduct background checks of employees and undergo safety and health inspections.

Though supporters say HB 2307 doesn’t take those regulations away, opponents say it would create a shield protecting unlicensed schools — several of which have been closed in recent years amid abuse allegations — from state scrutiny.

The measure would no longer require unlicensed schools to directly answer to the Department of Social Services. Instead, those facilities would be overseen by a new Child Protection Board, with more than half its members representing Christian schools.

Some fear bill could resurface

Based on Kelly’s comment, it appears the bill is dead for this session in the House. But child advocates and lawmakers worry because the measure did take a step forward, and they fear it could resurface. Moreover, a similar bill, sponsored by Sen. Mike Moon, R-Ash Grove, is sitting idle in the Senate. Moon was among the nine senators who voted against the boarding school bill in 2021.

“We are incredibly concerned by what this legislation is proposing to do,” said Jessica Seitz, executive director of the Missouri Network Against Child Abuse, formerly known as Missouri KidsFirst. “There was wide consensus just three years ago that some level of oversight and accountability on unlicensed schools was necessary to protect children from sexual and physical abuse.

“Any progress of a bill that could weaken this oversight and accountability, like this week’s committee vote, implies legitimacy.”

In February and April 2021, former students who attended Missouri religious boarding schools traveled to Jefferson City from across the country to testify in support of House Bill 557 at legislative hearings in both chambers.

The bill and its companion, House Bill 560, proposed requiring some state oversight over the state’s unlicensed Christian boarding schools, which were exempt from any regulations. The hearings moved some lawmakers to tears as they heard stories from former students about the physical and mental abuse they endured and how they tried to tell authorities but were ignored.

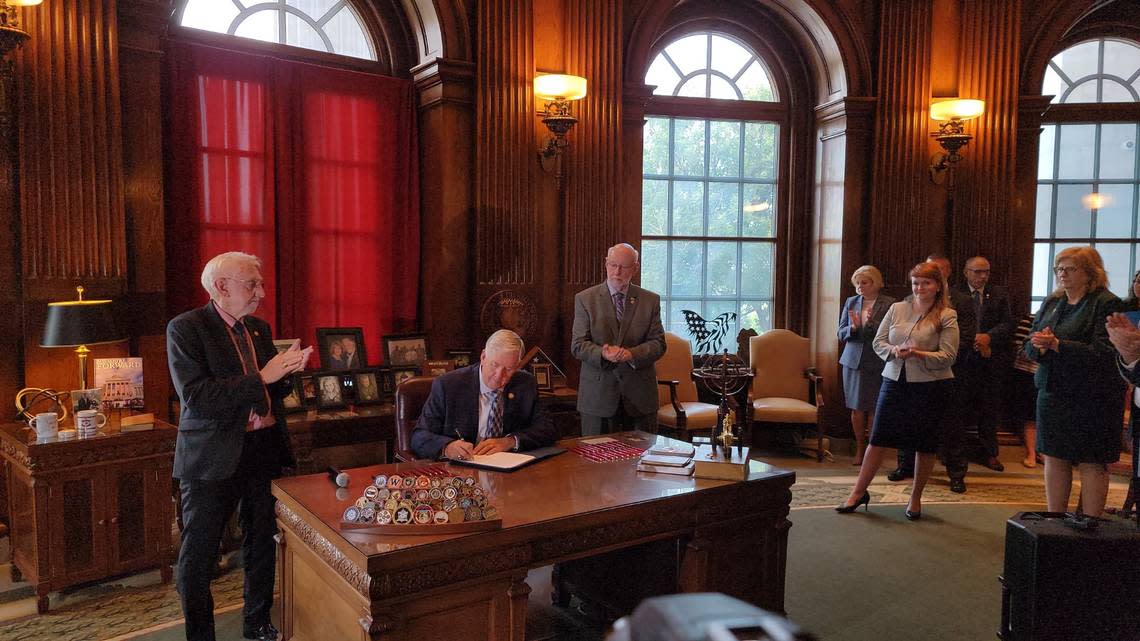

The bill passed both houses overwhelmingly, and Gov. Mike Parson signed it into law in July 2021.

“This bill would not have passed without them,” said Rep. Rudy Veit, a Wardsville Republican, a co-sponsor of the legislation, who spoke to several former students this week who were upset about the bill. “I understand their frustration. They’re upset at the idea that these people who did these things to them could still be surfacing, or people who are affiliated with them are still surfacing.

“They came and put their lives out in the open, and to see that it so quickly could turn around, they were insulted. And infuriated.”

‘Amazed that this could be happening’

After the bill passed in 2021, Veit said, the former students thought people finally understood what they had gone through in those schools.

“They were amazed that this could be happening, to see the issue coming back three years later,” he said. “The last time, they all came here and legislators heard their story. This time, they were caught off guard, and nobody had a chance to present their story.”

James Griffey, who attended Agape Boarding School in Cedar County from 1998 to 2001, testified before the Senate committee in April 2021. This week, he told The Star that the new proposal retraumatized former students, who feared it would undo the 2021 regulations.

“We fought so hard to get Bill 557 passed,” said Griffey, one of those who contacted Veit this week. “And to think that the same people we helped to protect the children of Missouri from are now trying to pass their own bill that will allow them to go back to having no direct governmental oversight sickens all of us survivors.

“The emotional struggle for me to fly back to Missouri to testify last time triggered so much PTSD, but it was worth it. And I was getting ready to book another flight out from California to come testify if need be.”

If those legislators who support HB 2307 cared about protecting children, Griffey said, they would work with the victims of these boarding schools to craft a bill that truly provides protection for the children of Missouri. Like the sponsors of HB 557 did, he said.

Former students, Adams said, have gone through a great deal to try and help current students who say they are being mistreated in some of the schools even today.

“Honestly, we sacrifice our anonymity, sometimes our dignity, and certainly our peace to fight for the safety and well-being of the kids who are suffering what we did,” she said.

Adams said she talked to Schnelting after Tuesday’s hearing.

“I suggested that a survivor be included on the (Child Protection) Board because that person would know what warning signs to watch for,” she said. “He seemed to think it was a good idea.”

Allen Knoll, of the Seattle area, who was sent to a reform school in Mississippi at age 10 and then to Agape Boarding School in Missouri in 1999 at 13, also testified before the Missouri Senate committee in 2021. On Tuesday, he was among those contacting Veit about House Bill 2307.

“Is this just the politicians trying to appease them (the bill’s supporters)? Like, ‘Hey, we brought it up, but it failed,’” he said. “I would say that in this political climate, this is just their appeasement, but it makes me nervous because it’s Missouri. And the reality is that none of us vote there.”

Knoll, who is co-founder of a troubled teen advocacy nonprofit, said if the proposal does happen to resurface, former students will rally the troops to oppose it. And that includes returning to Missouri to testify, he said.

“If that’s what it comes down to,” he said, “we’ll be there.”