As Tybee Island implements control measures for weekend, Orange Crush founder recounts challenges

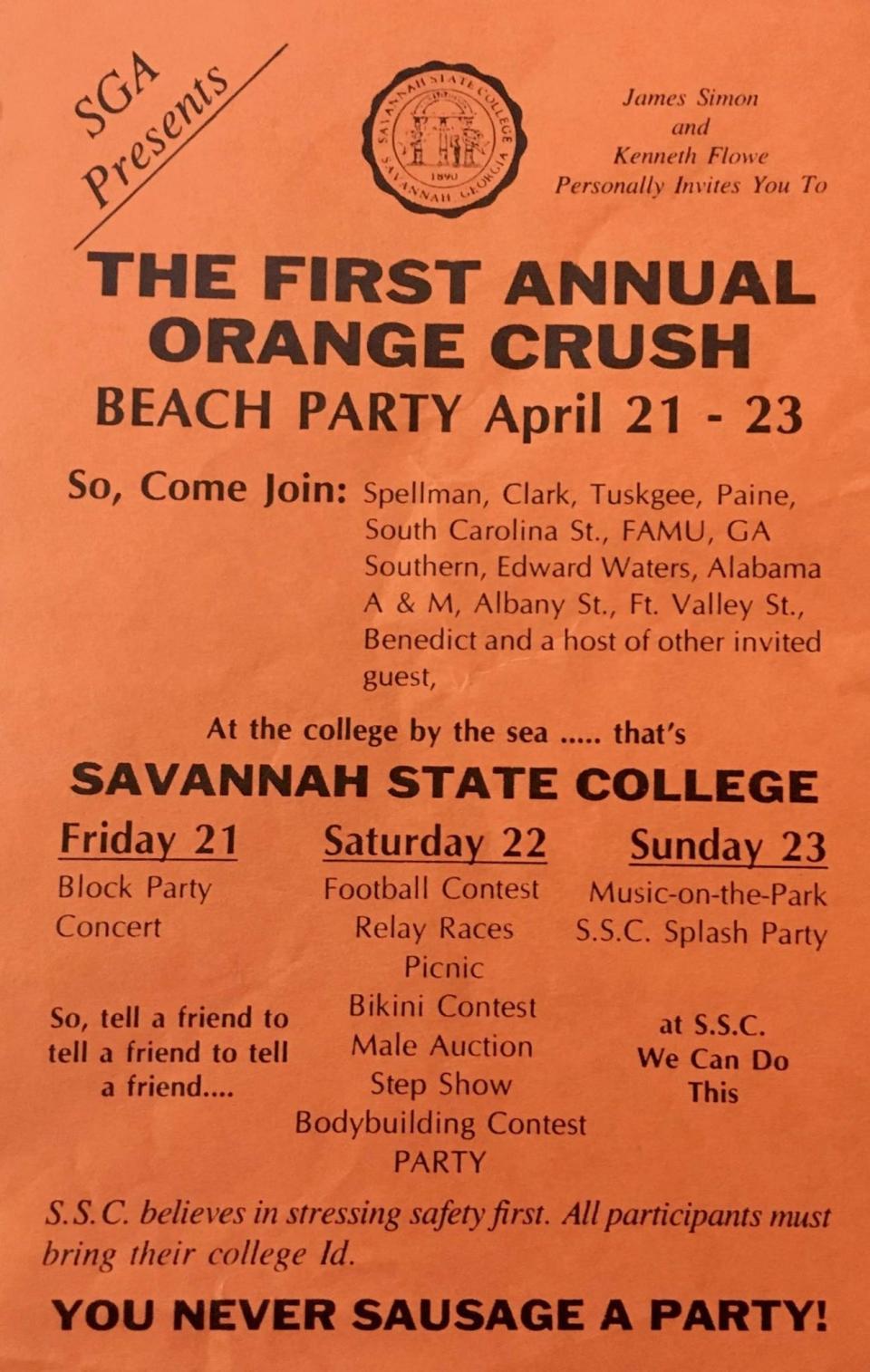

As a 19-year-old Savannah State University student in 1988, Kenneth Flowe knew he had to be strategic when getting a permit to host the first iteration of Orange Crush. However, he pulled the permit for the pavilion in November ― five months before the April beach bash he planned for Tybee Island.

"We figured they would try to figure out ways to block us from accessing the beach," Flowe said.

Flowe, who is credited with founding Tybee Island's Orange Crush, sees parallels between his experience creating the event, historic treatment of Black beachgoers and restrictions being put in place for the 2024 event on the island, including blocked roads and extreme parking restrictions.

"I think it's horrendous they're doing all this because this is a public beach," Flowe said. "I think that it's important for African Americans to be able to access public space without being harassed by policy makers. When you take that tactic, then you get folks who are saying, 'I'm coming on that beach, come hell or high water.'"

Two decades before Flowe decided that a huge beach bash was the best way to put SSU on the map for Historically Black Colleges and Universities, 11 Black students were arrested at Georgia's first wade-in, a demonstration similar to a sit-in, on Tybee.

Recent related news: Kemp signs bill holding Orange Crush organizers liable for costs of unpermitted event

Orange Crush weekend 2024: Everything you need to know about the event

Prior to the wade-in demonstrations, Black people were forced to travel outside of the city for public beach access. After three years of wade-ins, Tybee's beaches were integrated by October 1963.

"They were jeered at by beachgoers and arrested for disrobing in public," Flowe said. "As a result of this, those young folks who were simply trying to use public water had criminal records. I just anticipated that the authorities would try to figure out a way to prevent the beach party if I didn't conduct myself properly."

Ahead of the inaugural Orange Crush, Flowe and other members of the student government invited students from Spelman College, South Carolina State University, Florida A&M University, Alabama A&M University, Clark Atlanta University and more.

The event, Flowe claimed, was "very well organized," and on April 22, 1989, the first Orange Crush had a football game, relay races, picnic, bikini contest, a male auction, a step show and a body-building contest.

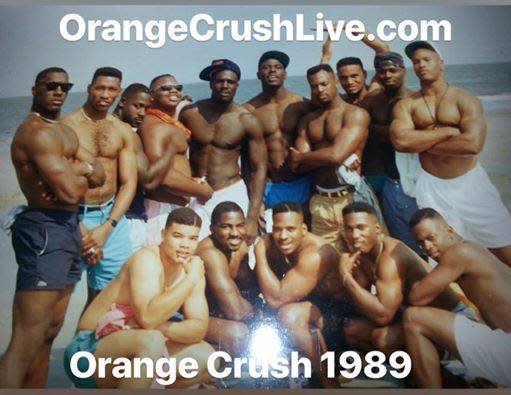

"To me, it looked like 5,000 students showed up, but it might have been 500," Flowe said. "It was really hard to keep track because that wasn't really on our mind and there were just so many students, coming from so many places. Apparently, it was enough for the authorities to feel the need to call out various police agencies."

The two main things Flowe remembered from the first Orange Crush: a lot of people and a lot of law enforcement.

The festival continued to be held and sponsored by SSU, drawing in students from HBCUs in Georgia and along the East Coast, until 1991. SSU severed ties with the event after a dozen arrests, a stabbing and drowning at a singular festival, but by that time Tybee Island had been solidified as a place for HBCU spring break celebrations. It continued, unpermitted, drawing crowds year after year.

Organizers and event promoters began taking advantage of the attendance and promoted events on social media that would fall on the same weekend, and as the crowd grew, crimes occurred, setting up conflict between attendees, residents, law enforcement and city leadership.

In attempts to combat the large crowds and the potential for violence, the City of Tybee has implemented aggressive regulations in the past. In 2018, it prohibited open alcoholic beverages and implemented traffic stops and property searches, limited housing rentals, noise and some restaurants and businesses closed.

This resulted in a mediation between the group Concerned Citizens of Tybee and the city by the U.S. Department of Justice. The agreement states that officials should not treat Orange Crush differently than any other special event, permitted or not.

The now unpermitted event known as Orange Crush by locals is shaping up this year to look similar to the event of years past: with lots of law enforcement and barricades to prevent the strain on Tybee Island's resources that it brought last year.

In 2023, the third weekend in April brought more than 111,000 people over the course of three days, and the high volume of people caused clogged roads, traffic accidents, a road rage incident resulting in a shooting, crowding and complaints around drug and alcohol abuse, noise, illegal parking and litter, according to the city.

Tybee's efforts to control Orange Crush crowds

Despite efforts to obtain permits from promoters of previous Orange Crush events, no permits were approved, and Tybee Island officials have set up restrictive access to the beach between April 16-21, including:

Barricades on Butler Avenue will prohibit on-street parking, beginning April 16.

There will be a road safety checkpoint on April 19 going into Tybee.

No on-street parking will be available on Butler Avenue from Second Street to Tybrisa Street.

14th and 15th Street Parking Lots will be closed.

16th Street Parking Lot will be reserved for City of Tybee Island Parking Decals only

Illegally parked vehicles on public property will be towed to the 15th Street parking lot.

An emergency lane will be designated on U.S. Hwy. 80 for First Responder vehicles only

Traffic protocols will be enforced with strategically placed barricades along Butler Avenue to manage the flow efficiently.

Side street entrances on the western side of Butler Avenue will be closed from Lovell Avenue onwards.

Access to Lewis, Miller and Second avenues will be blocked from the Hwy. 80 entrance.

No turns east onto 14th, 15th or Tybrisa Street from Butler Avenue (Residents: Eastbound access available on 14th and 15th Streets)

The island will also have more than 100 extra law enforcement officers, including from the Georgia State Patrol, Department of Natural Resources and Chatham County Sheriff's Office.

Destini Ambus is the general assignment reporter for Chatham County municipalities for the Savannah Morning News. You can reach her at dambus@gannett.com

This article originally appeared on Savannah Morning News: Orange Crush founder talks restriction, challenges in event's history