Trio of NY groups make last-ditch bid to block congestion pricing from taking effect next month

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

New Yorkers are making a last-ditch effort to stop congestion pricing from taking effect next month, arguing traffic won’t go away but will just be shuffled around — not to mention myriad collateral consequences on commuters and residents.

A marathon of oral arguments began Friday morning in Manhattan federal court in three separate lawsuits — one brought by United Federation of Teachers President Michael Mulgrew and Republican Staten Island Borough President Vito Fossella, another by New Yorkers Against Congestion Pricing Tax and the third by a second group of city residents — who all want to stop the $15 toll set to launch June 30.

Lawyers for the opponents argued in the packed courtroom that the environmental impacts — including pollution, traffic and economic effects — were not properly analyzed and that the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) fast-tracked a study that wrongly found congestion pricing would have “no significant impact” on New Yorkers.

“Our case is not an attack on the concept of congestion pricing,” plaintiff lawyer Alan Klinger told the judge.

“What this case is about is whether a proper assessment was undertaken” Klinger said. “When you look closely, the defendants’ program is not eliminating congestion, it is redistributing it.”

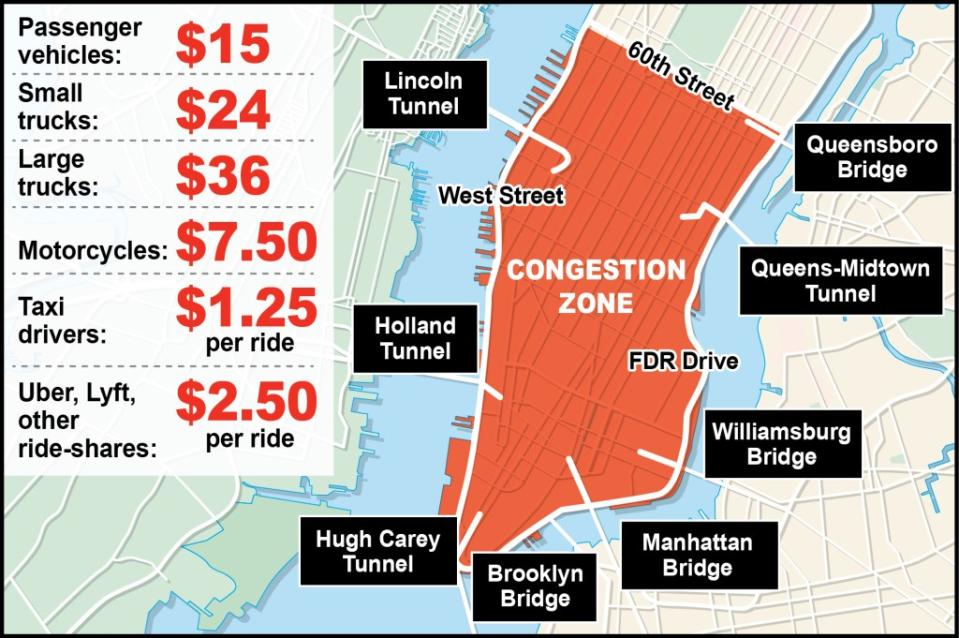

The controversial plan — which would be the first of its kind in the country — would charge drivers $15 per day when they enter Manhattan below 60th Street between 5 a.m. and 9 p.m. and $3.75 to drive in the area overnight.

Small trucks would be charged $24 and large trucks would be charged $36 under the program.

Klinger, reps plaintiffs in two of the three suits, said that many residents would face hours of extra time commuting each day, increased pollution, more expensive taxi and ride-share trips — and the onerous cost of the toll itself.

And while the record of the plan’s review has thousands of pages, Klinger argued the Metropolitan Transportation Authority failed to come up with proper mitigation measures, despite finding there would be spikes in pollution.

“This is supposed to be an encompassing process and we think it was anything but that,” Klinger claimed.

But Judge Lewis Liman pushed back, pointedly asking if the 44-day public review period that the MTA held from Dec. 27 through March 11 was insufficient.

Klinger said he was referring to the record of thousands of pages, but still said: “Yes, your honor. We don’t think that’s sufficient.”

“I guess they should have done fewer pages of analysis,” Liman quipped.

“Or a more complete analysis,” Klinger specified, later charging that the defendants “attempt to bury us in mountains of minutia.”

The MTA board voted to pass the $15 toll in March, with even greater tolls for trucks.

The agency was required by a state law signed by then-Gov. Andrew Cuomo in 2019 to approve a tolling structure that will generate $1 billion annually to pay for new subway trains, signal overhauls, a new expansion of the system into East Harlem and other major projects.

Klinger argued Friday the MTA came up with its congestion pricing plan out of a “desperate need to get funds to improve mass transit here” — setting the figure for those improvements at $15 billion so that all other alternatives would come up short financially.

Another plaintiff lawyer, David Kahne, noted that in the 900-page environmental assessment of the plan, “There are precious few pages devoted to mitigation.”

“They are saying the ultimate tolling structure will decide what the mitigation will be,” Kahne said, adding that full mitigation proposals should have been included in the review.

The plaintiffs are asking Liman to overturn the environmental assessment report and to send the plan back to the MTA and the FHWA to start the review process over again.

Zachary Bannon, a lawyer for the FHWA, said the plan’s review was extensive and has been conducted with public feedback “from its inception until today.”

The environmental assessment “resulted from a tremendous amount of stakeholder engagement,” including holding “dozens of webinars with interested parties,” receiving and responding to tens of thousands of comments and hearing testimony from hundreds of people.

The collaborative process is still ongoing as the MTA continues “to work with environmental justice groups” and “there is a reevaluation process going on right now” — which must be finalized before the toll can take effect, Bannon said.

Later, another FHWA lawyer, Dominika Tarczynska, said the review will address the concerns that the plaintiffs have by analyzing the specific toll plan and ensuring that it will have “no significant” environmental impact.

“FHWA is currently conducting a reevaluation to determine the very thing that the plaintiffs are here seeking today,” she said.

The MTA also has planned mitigation including studying 102 intersections that they determined would see the greatest increase in traffic and coming up with signal timing that would vastly reduce gridlock, Bannon said.

Elizabeth Knauer, a lawyer with the MTA, insisted that the plan would not only benefit the congestion zone but also other local neighborhoods and assured the judge that traffic would only “increase, to a small degree, in some areas.”

“We are not trying to brush anything under the rug, as the plaintiff suggests,” she said.

Knauer also highlighted that the mitigation efforts by the agency are significant, with a $155 million “mitigation package to be funded and implemented” over a five-year period to address adverse effects.

In the afternoon, lawyers for the UFT and activist group New Yorkers Against Congestion Pricing Tax defended against arguments their cases, both filed in January, should be dismissed over the statute of limitations.

A lawyer with the FHWA claimed that highway projects must be opposed in court within 150 days of an Environmental Assessment getting released, a rule put in place to help move projects along and prevent them from getting locked up in litigation.

Liman will likely rule at a later date.

A similar hearing was held in a New Jersey federal court over the course of two days last month in a suit brought by NJ Gov. Phil Murphy.

That case argued that the effects of congestion pricing — including the cost, pollution and increased traffic — would be felt in the outer boroughs and in the Garden State, but that insufficient mitigation was offered for them.

That suit also claims the review process was insufficient and in fact, the FHWA merely “rubber stamped” the MTA’s plan.

Judge Leo Gordon said at the end of the hearings that he planned to issue a ruling before the toll goes into effect.