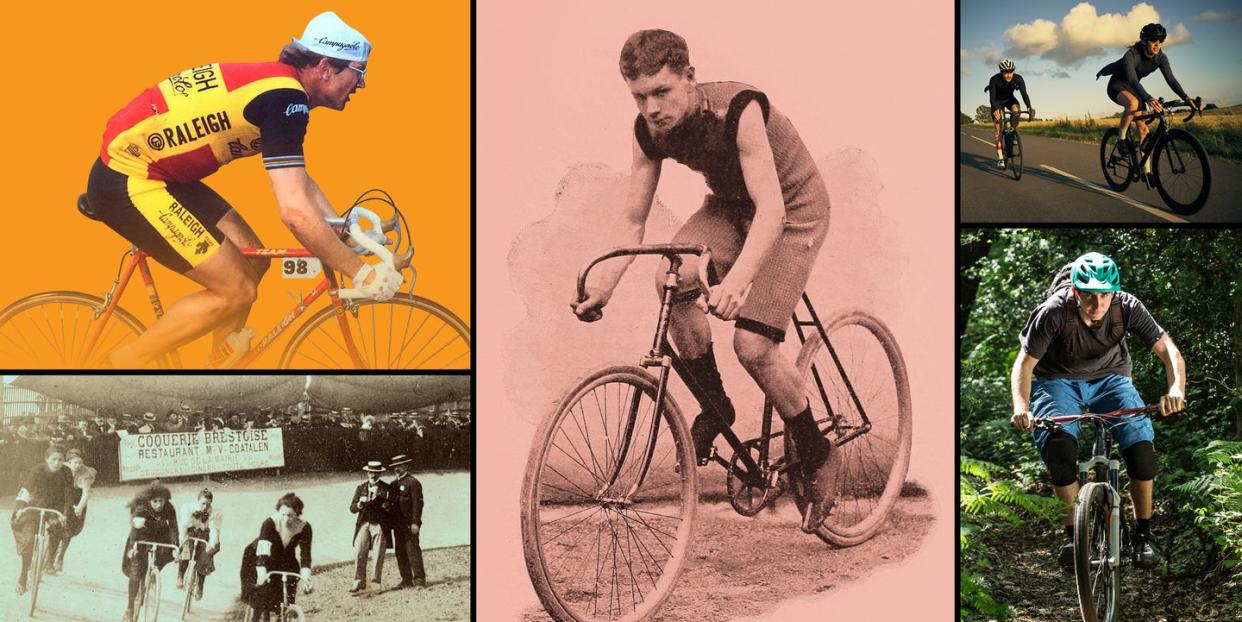

The Totally True, Totally Weird History of Your Cycling Shorts

Two majorinnovations in this decade made cycling a safe mode of transportation for the masses. At the time, the bike of choice was the penny-farthing, also known as “the ordinary,” which placed the rider precariously high and required a running start to mount it. In 1885, the “safety bicycle”-so named because of its equally sized wheels that placed the rider closer to the ground-was invented, and quickly began replacing its sketchier predecessor. Inflatable tires were invented three years later. Though bikes saw a boom in this decade, most people still rode in their day-to-day clothing, even if it wasn’t always comfortable.

As

bicycles became widely available, specialized garments appeared. Riders typically wore homemade wool shorts (black, to disguise the fact they were sitting on an oiled leather saddle for hours) and long- or short-sleeved wool jerseys, often with a high collar for warmth. Most wore wool socks and slipper-like leather shoes that were easy to get in and out of toe cages. Wool was the fabric of choice because it stayed warm even when wet from rain or sweat (one of the reasons it’s still popular for socks and base layers today. Today’s wool also doesn’t stink and is fast-drying). But it was also scratchy, and sagged when it got wet. Chafing from homespun wool shorts was an enormous problem, and riders would sometimes finish races bleeding down there.

M

anufacturers eventually addressed the chafing problem by sewing a piece of leather into the seats of shorts. A “chamois” is a European mountain-goat-like animal, and the first chamois was made from actual chamois skin. But as chamois numbers began to dwindle, makers began using sheepskin, and what we now call “chamois cream” was a kind of leather conditioner applied directly to the chamois to soften it and mitigate damage to the skin.

A

s professional racing grew in the 1930s and ’40s, some manufacturers fashioned their chamois out of deer leather, which is softer than sheepskin. Still, the leather did nothing to damp vibrations or cushion the rider-its only purpose was to reduce friction between skin and scratchy, wet wool.

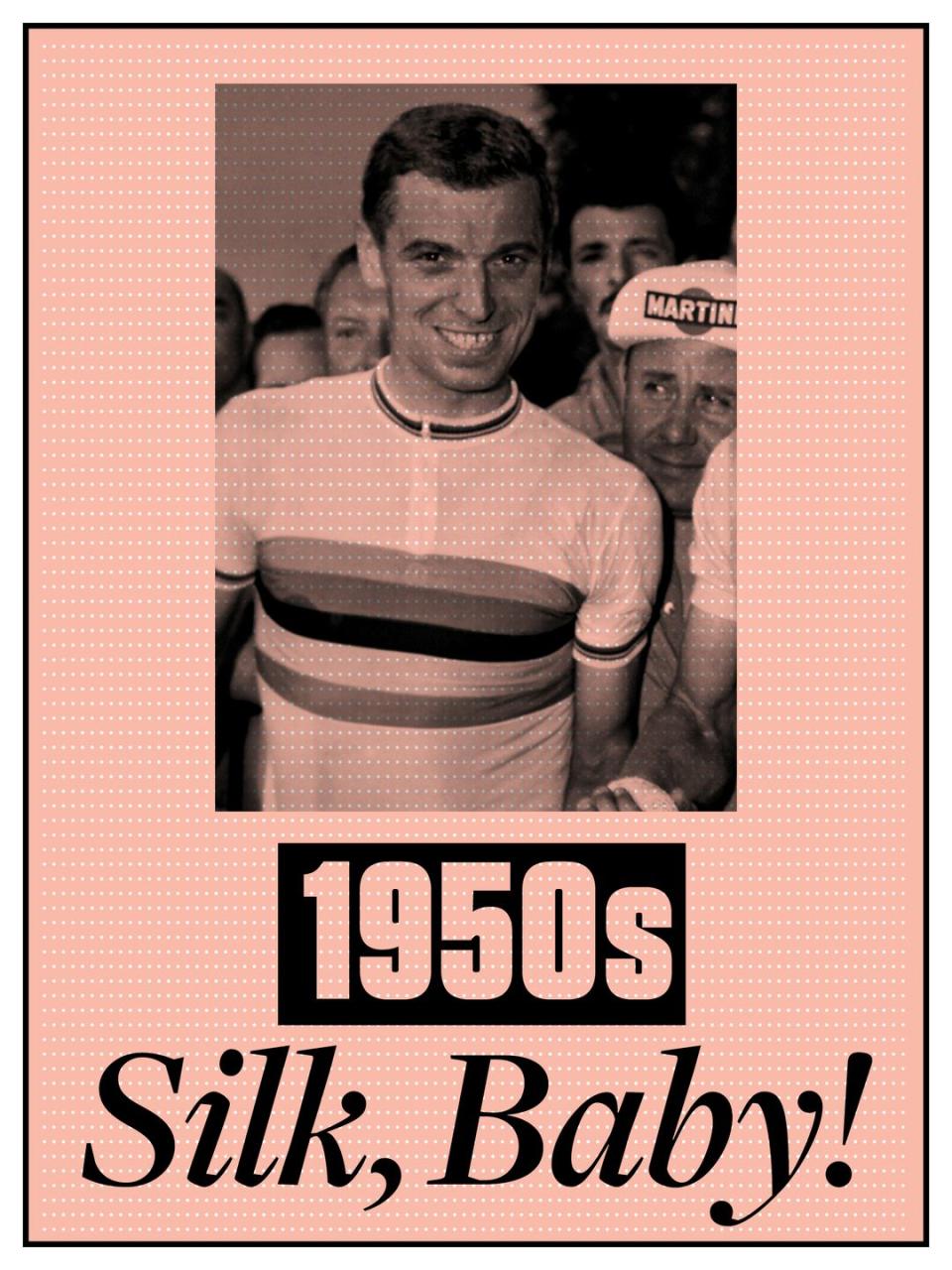

Ita

lian clothing maker Armando Castelli and his son, Maurizio Castelli (of the namesake brand), were the first to introduce silk jerseys to the peloton in the early ’50s. Silk was lighter and cooler than wool, and took color much more vibrantly. This allowed jersey makers to use colorful dyes, as well as screen-print sponsor logos directly onto the fabric in brighter, richer colors.

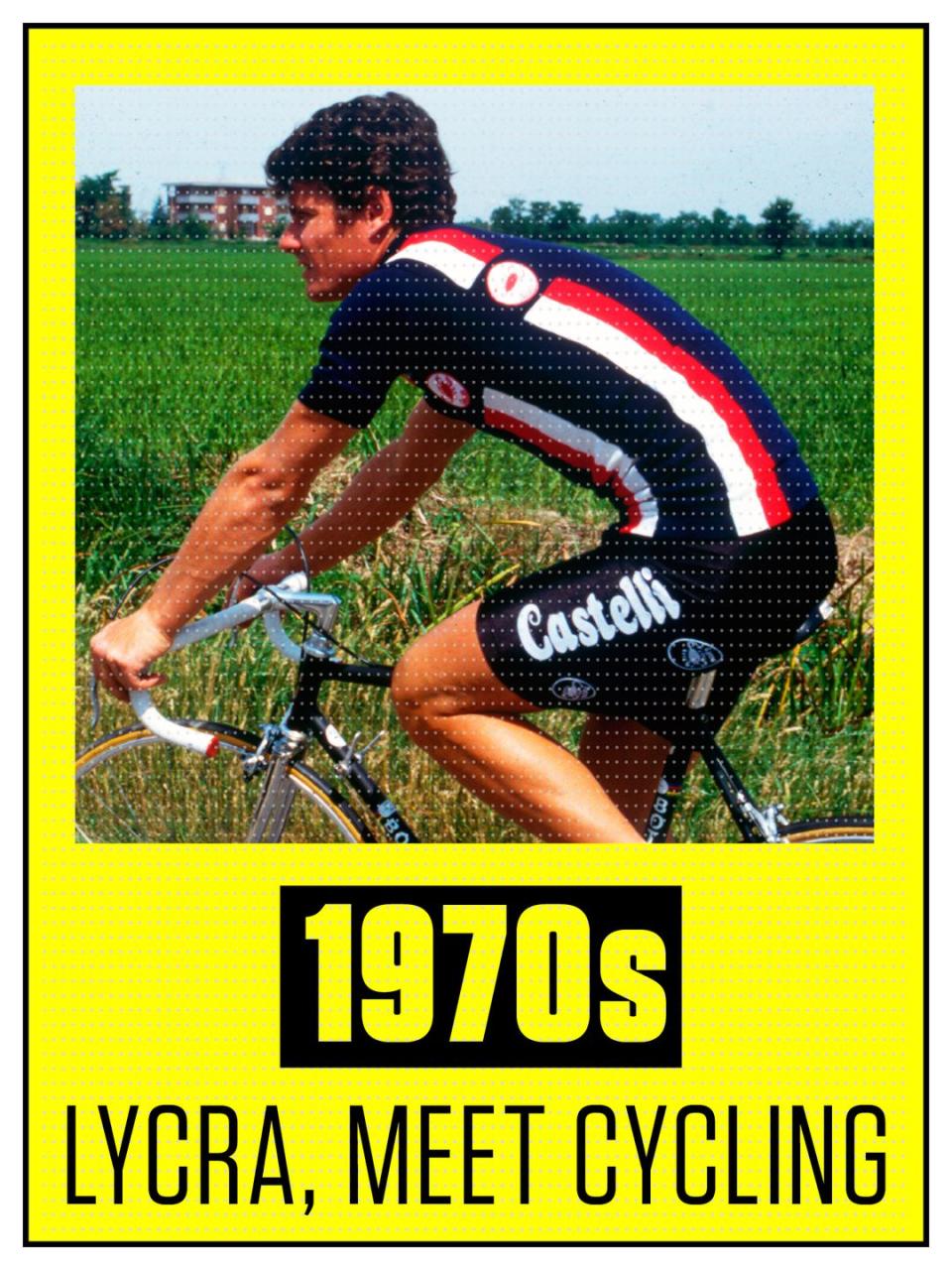

Cyclists began

donning a new breed of synthetic fabrics including nylons, polyester, polypropylene, and acrylic, which were sweat-wicking, light, skin-tight, stretchy, and easily dyed. After a decade of research, Lycra was invented by DuPont Manufacturing in 1959, and initially was used mainly by speed skiers and swimmers. Lycra was thinner and stretchier back then (don’t try to picture it). Assos constructed the first pair of Lycra cycling shorts for the Ti-Raleigh team in 1976, and Castelli popularized the trend with its own made-for-public version a year later, a black one-size-fits-all pair of shorts. Cotton and wool shorts became obsolete. Word got around about this new type of cycling shorts, and customers lined up around the factory on the day they were introduced.

O

riginally, racers wore their wool cycling shorts with suspenders to hold them in place and prevent excess constriction around their waists. In 1979, shoulder straps became integrated into the design of Lycra shorts. Outdoor-gear manufacturers, like Descente, that served multiple industries developed similar combined bib and suspenders designs in the 1980s in tandem for cycling and other sports, notably skiing.

I

n 1980, Castelli developed the first padded, nonleather chamois. This original version was cotton-based, but soon after, microfiber material was invented in Japan and brought to Europe, where apparel maker De Marchi adapted it to create foam padding. As the new, less-expensive foam chamois took off, brands developed new chamois creams that helped eliminate friction and discomfort on the skin, rather than simply softening hard leather.

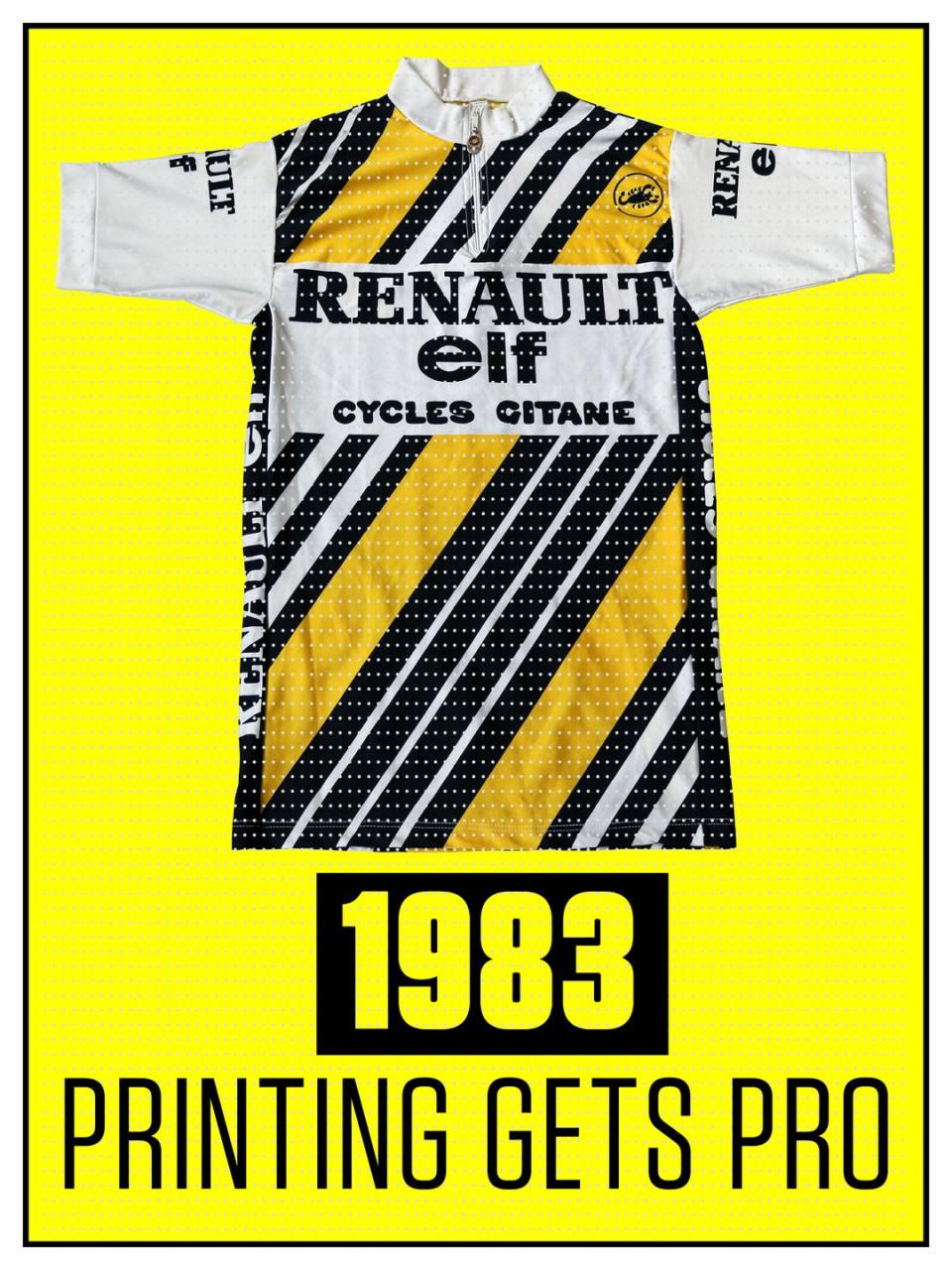

Castelli also pioneered sublimation printing, enabling a rainbow of colors and detailed designs to be transferred to jerseys, which allowed riders to sport sponsor logos on their chest, back, and shoulders. Everything up until then was done by color blocking (actual pieces of solid dyed fabric stitched together), silk screening, flocking, and embroidering, which created much simpler jersey designs, often with logos on just one side. Sublimation allowed for easier application of more complex logos that were truer to the company’s design. This introduced a new age of professionalism and all-important sponsorship dollars to the sport. Bernard Hinault wore the first sublimation printed and windproof jersey to win the Fleche Wallone Classic that year, emblazoned with his team sponsor’s logo, Renault Elf.

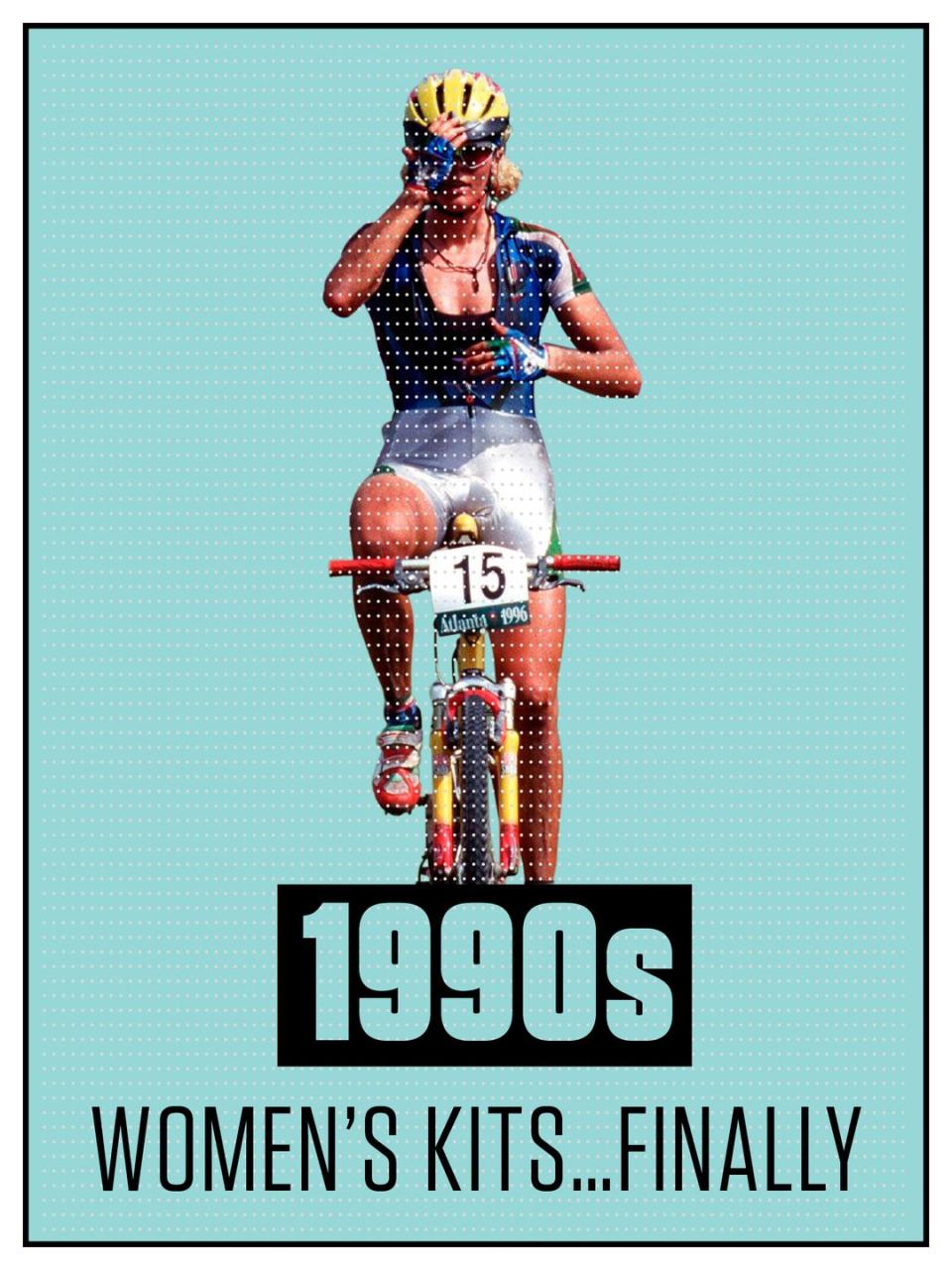

W

omen who raced bikes from the 1940s to the 1980s dressed in the same clothing as men. Women’s cycling wasn’t an Olympic sport until 1984 (almost a century after men’s cycling debuted at the Olympics). In the mid-1990s, women’s-specific cycling kit finally made its way to market in different cuts and sizes and with different chamois designs. Today, the demand of the women’s market has influenced designs like bib shorts that make nature stops easier.

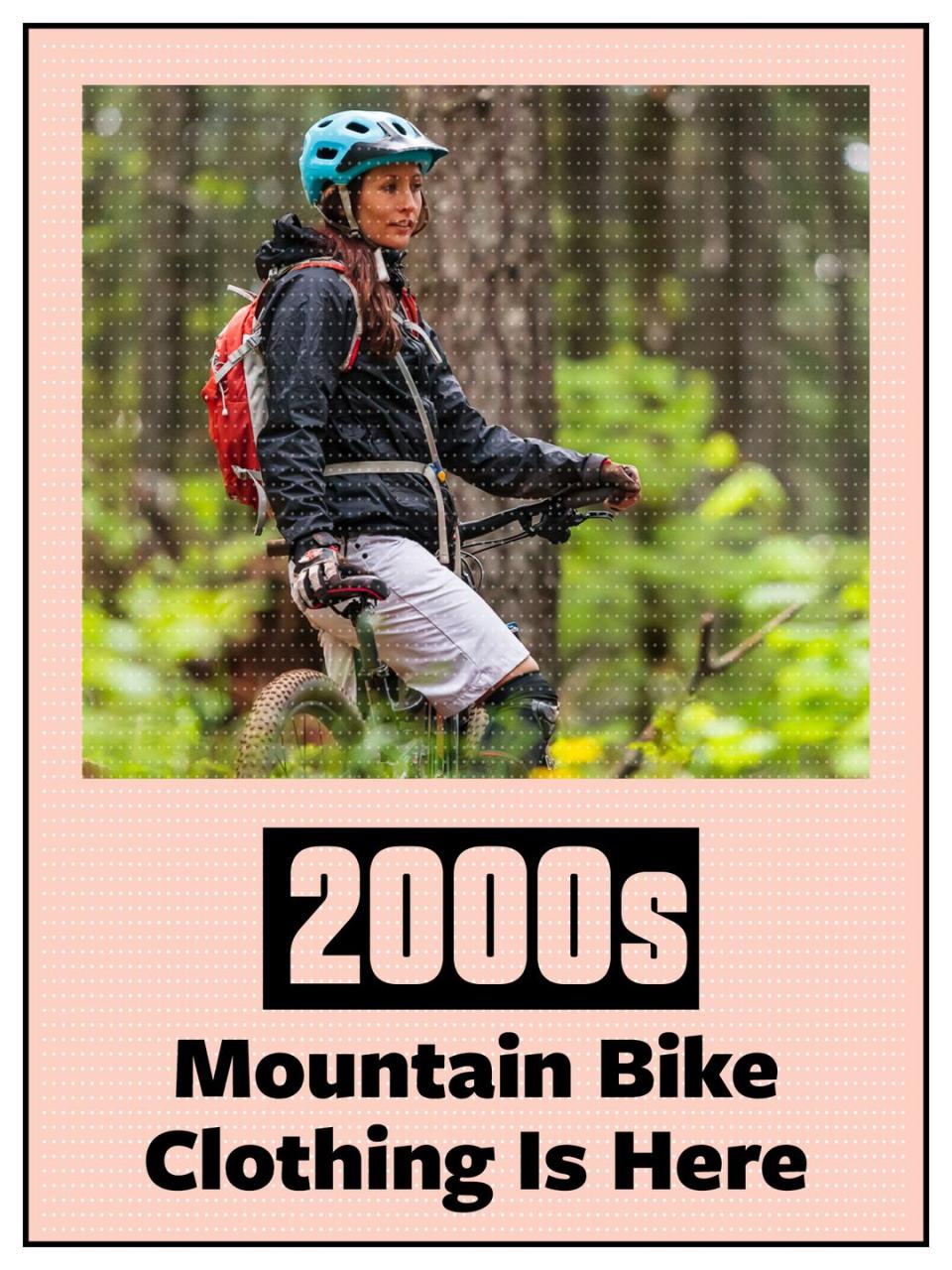

M

ountain biking gained serious popularity in the late ’90s, and with it came the rise of its own style and culture. As mountain bikers tried to distinguish themselves from roadies, they looked to other influential sports like surf, skate, and snowboard cultures. They adopted clothing that was more protective and less concerned with pure aerodynamics, like baggy shorts, helmets with visors, and body armor.

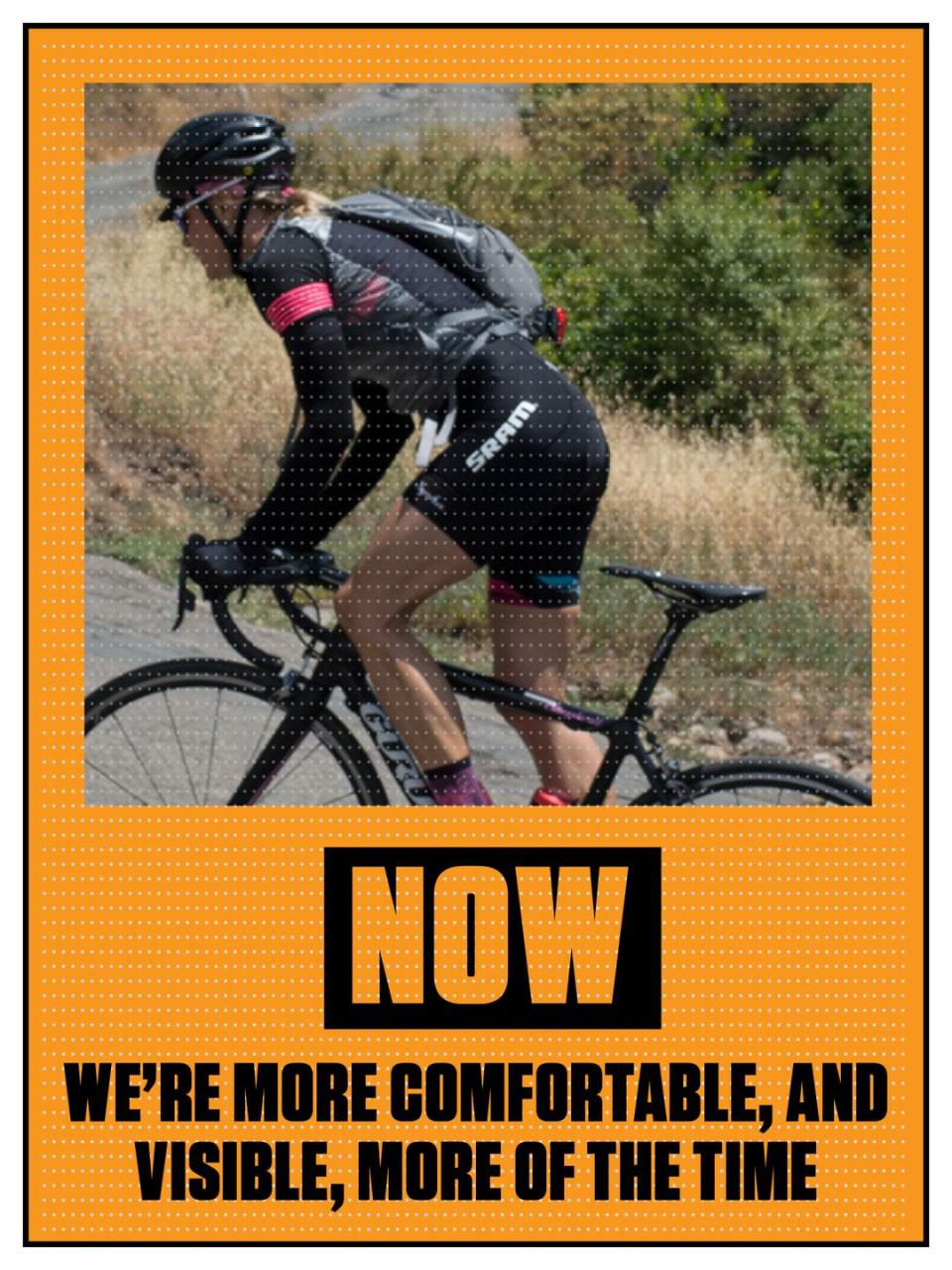

F

undamentally, the cycling clothing we wear today looks similar to the kits of the early aughts, but continued R&D has brought new levels of performance in warmth (for cold-weather clothing), breathability, water- and wind-resistance, and visibility, so our clothing can keep us safer and more comfortable. GORE’s R7 Gore-Tex Shakedry hooded jacket ($300), for example, repels water so well that, as advertised, you can shake off the water droplets, yet is breathable enough to keep you from overheating on climbs. Temperature-sensitive fibers in the Mission Workshop PNG jersey ($180) which employs 37.5 moisture management system that actively pulls vapor from your pores before it turns to liquid sweat which improves the body’s ability to cool itself. And hi-viz accessories like Bontrager’s Halo S1 softshell shoe covers ($90) use the theory of biomotion-that objects moving in a nonlinear fashion are more easily recognized as humans-to help drivers more readily see cyclists.

Image credits: Lead: Adoc-Photos/Corbis via Getty Images (female cyclists); Courtesy Smithsonian Libraries (cyclist); Courtesy Accell North America (Raleigh); Luxy Images/Getty Images (mountain biker); Pixdeluxe/Getty Images (two cyclists); Courtesy Smithsonian Libraries (1880s, 1890s); Keystone-France/Gamma Rapho via Getty Images (1930s); Courtesy Castelli (1950s); Zach Kutos (chamois); Andy Storey/Prednas Ciclismo Limited (Renault Elf); Alexander Hassenstein/Bongarts/Getty Images (1990s); Brandon Sawaya/Getty Images (2000s); Jake Szymanski (now)

('You Might Also Like',)