Still $600M in potential savings from Second Ave Subway designs, even after MTA trims: Post analysis

The MTA could potentially find another $600 million in savings in its bloated plans to extend the Second Avenue Subway, a Post investigation found — as the agency faces pressure to prove it’ll spend its upcoming congestion toll windfall wisely.

New York is potentially just about three months away from launching a controversial $15 daily charge on cars that drive below 60th Street in Manhattan, raising $1 billion a year for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority to spend on projects, such as its expansion of the Q line to East Harlem.

“MTA management is ineffective, and handing more money to unelected bureaucrats will not fix the MTA’s problems,” testified real estate agent Lucas Callejas, 38, of Inwood, during a public hearing about the congestion fee plan Monday.

“I absolutely don’t trust the MTA with my money … They spend like crazy,” added Dana Matarazzo, 40 an oncology nurse at Memorial Sloan Kettering from Staten Island, who spoke to The Post after testifying against the toll.

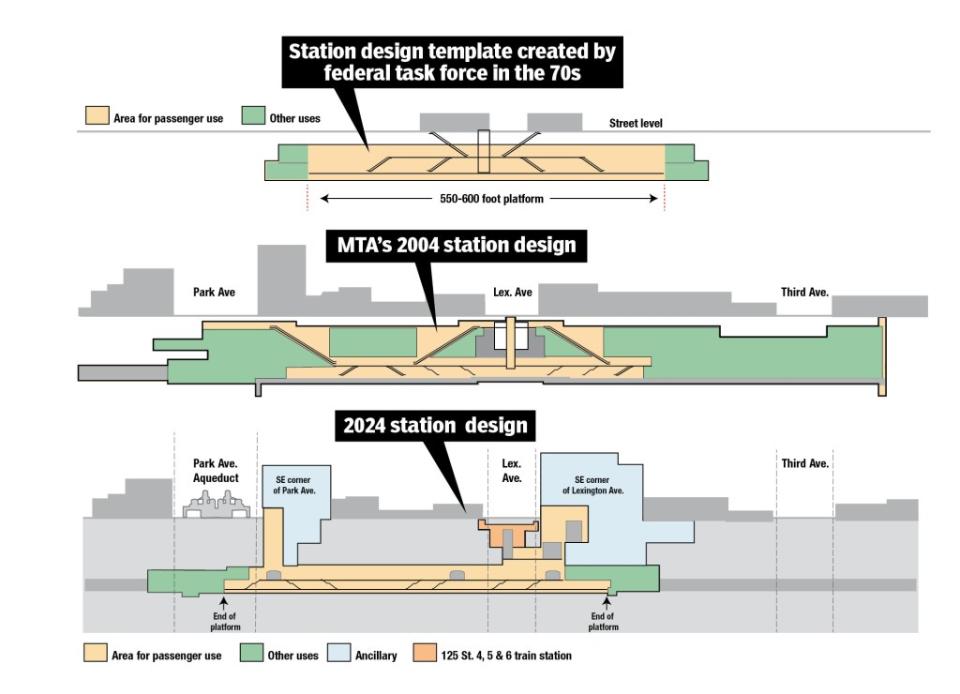

MTA officials announced last month they shaved $300 million off the $6.9 billion total estimate to extend the Q line from its terminus at 96th Street another 1.5 miles up Second Avenue and then westward along 125th Street to Lexington Avenue.

But The Post’s analysis found another $600 million in savings in the MTA’s station designs, when compared to what it would cost to build a similar project overseas.

While the tunneling costs are in line with those of other major cities, such as London and Rome, the station costs and designs remain in an entirely different league, The Post’s analysis revealed.

Before the recently-announced trims, the MTA’s budget for tunneling, trackwork, stations and power, computer and radio systems was estimated to be $4.1 billion.

The new, “more efficient” station designs have helped lower the figure to $3.8 billion — still more than the $3.2 billion would cost to build a similar project in London, the most expensive of the European cities examined by The Post, in a worst case scenario.

Experts and researchers zeroed in on two major factors that have pushed the MTA’s station costs to levels not seen elsewhere: The amount of area set aside of passengers to circulate on mezzanines before heading down to the platforms; and the amount of “back of house” areas sealed away from public view that provide space for storage closets, mechanical functions and break rooms.

For instance, the designs for 106th Street, the first of the three proposed stations, call for the construction of a 550-foot long mezzanine that’s 30 feet wide, even though the station will be roughly 50 feet deep and federal documents show it will be used by just 1,860 passengers during the peak AM hour.

That’s enough room to guarantee each one of those straphangers nine square feet of personal space on the mezzanine for an hour at the height of the morning commute, enough for a person to stick out an arm for the entire time and not touch another soul — or to fit roughly 25 one-bedroom apartments.

For comparison, the proposed 116th Street stop — which sits at roughly the same depth and will be used by a nearly identical 1,670 riders during the peak hour, per the filings — has two tiny mezzanines at its entrances that combine for just 4,860 square feet of space.

The MTA refuses to say how much it expects to spend on each of the new stations or to say how much of the $300 million in newly announced savings came from design changes.

But MTA filings with federal regulators before the latest tweaks were rolled out pegged the budget for all three proposed stops at $3.4 billion, which would mean the budget remains at least $3.1 billion — or $1 billion per stop.

Authorities in London could build three similar stations for approximately $2.3 billion, The Post’s analysis found.

The analysis incorporated some of the most over-budget and delayed stations recently built in the British capital, including the recently-opened Bond Street stop, on the Elizabeth Line, which ran over budget several times and was managed so badly that the contracting firm was fired.

The station was built using the same construction techniques that the MTA will use for 125th Street and fits trains that are 100 feet longer than the ones the MTA runs on the Q.

It would cost $1.2 billion, when adjusting for MTA train size and currency conversions.

The Woolwich station, also on the Elizabeth Line, was built using the same techniques the MTA will use for the 106th and 116th Street stops.

A version of the design adjusted for the size of the Q train would cost between $500-$600 million a pop, the analysis showed.

Both of the London stations dedicate far less space than the MTA designs do to back-of-house functions, meaning the digs are smaller.

The analysis used the MTA’s formula for estimating inflation to equalize and project the costs in 2027 dollars.

Experts, however, said the MTA’s new designs for the heavily reworked 125th Street illustrate a structure that is far smaller and less complicated than the one first proposed in 2004.

One of the biggest changes, MTA officials said in a briefing, was a decision to shove many of those back-of-house rooms into the air towers the agency already has to build to ventilate the deep station. They estimated that is 5-10 times cheaper than digging them underground.

Its new design moves nearly four times as many passengers per square foot as the design at 106th Street, the Post’s analysis found.

The feds granted permission to rework the 125th Street station design in 2020 in an earlier second round of reviews for the East Harlem leg, but officials not reveal the full scope of the overhaul until stories ran in The Post highlighting the size of the original 2004 design. The first round of tweaks approved by regulators in 2018 allowed the MTA to put the 116th Station in an empty piece of existing tunnel.

The three rounds of reviews have shaved an estimated 17% off of what could have been a $7.6 billion total price tag, records show. Officials have said the third round of reviews remains ongoing.

The overall now-$6.6 billion budget for the East Harlem expansion also includes $245 million for land purchases and eminent domain, $559 million for outside engineering, design and management firms, plus a whopping $943 million for a budget reserve.

The project’s construction costs alone could have been as high as $4.4 billion had the MTA re-used the station designs from the Second Avenue Subway’s Upper East Side extension, a much-delayed project that shattered cost records.

“That’s the hard part, turning this ship around,” said Eric Goldwyn, who lead a team of researchers at New York University that revealed how oversized the MTA’s Upper East Side designs were compared to those used in Stockholm, Rome and Istanbul, dramatically inflating costs.

“When people asked them about our research, they said ‘we were a–holes,’ basically,” Goldwyn added. “I’ve been encouraged by what I’ve seen, but there are absolutely things to keep looking at.”

MTA chairman Janno Lieber attacked the NYU team and its 400-plus page report previously, deriding the researchers as being part of an Internet “subculture” and claiming the NYU team used the wrong cities when comparing MTA costs and designs.

The Post’s own subsequent stories addressed those criticisms head-on by comparing the MTA to Europe’s largest and most famous capitals, London and Paris.

Experts, like Goldwyn, and veteran transit insiders say that the MTA overbuilding is driven in part by a backward system for developing mega-projects: It hands consultants a blank sheet of paper, gets excessive designs back and then has its strapped review department pare them down.

The MTA’s major projects arm has roughly just 100 people on staff, while London has six times as many and Paris’ transit agency has a staff estimated at 2,000.

The MTA declined to comment.

Additional reporting by Reuven Fenton