State of Texas: ‘My worst nightmare,’ Austin hospital crash highlights need for safety barriers

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

AUSTIN (Nexstar) — Nadia and Levi Bernard stared at the swirl of colorful fish with their toddlers, Sunny and Rio. A large glass aquarium near the emergency room waiting area caught the attention of the boys, who wanted a closer look.

Nadia was tired but glad to have her family there for support. She had just undergone a CT scan. Soon, she would find out what was causing the sudden and persistent pain to her left side. There are too many sick people here, she thought, happy to move to a quieter spot.

As she waited, she watched her sons fixated on the different fish. Whatever the test results, moments like this helped wash away any worry.

The next moment was a flood of chaos. Shattered glass, splinters of wood, water everywhere. Lights, smoke and alarms. A car where it should not be.

“A lot of people asked me how it felt… I think, the best description would be like being in the ocean. When a big wave comes and smashes you and pushes you and there’s this force just like taking you,” Nadia recalled months later, sitting on a couch next to her husband.

“And, I just remember – keep telling myself, ‘You’re going to be okay. You’re going to be okay.’ Like, closing my eyes, and just, like, waiting (for) it to stop,” she said.

“You were thinking, ‘I just have to hold on,’” Levi added. “I was thinking, ‘Okay. So this is what dying feels like.’”

A KXAN investigation discovered what happened that day is surprisingly common. We found more than 300 crashes at medical centers in the last decade. Experts say all of them could have been avoided – including the incident at St. David’s.

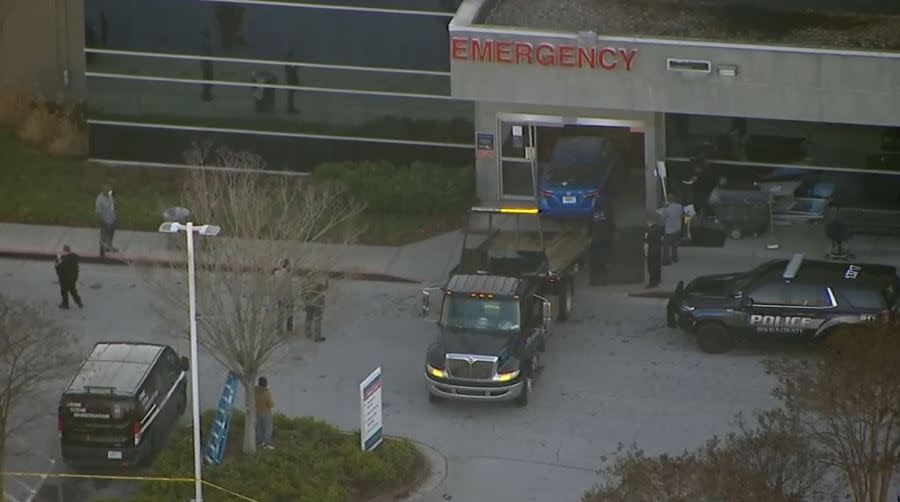

On Feb. 13, 2024, at 5:35 p.m., an Acura sedan slammed through the emergency room doors at St. David’s North Austin Medical Center.

Before Levi was knocked unconscious, he remembered hearing “a large crash.” He turned his head and saw the flash of a white car.

Cell phone video taken by a witness captured the immediate aftermath: the red glow of the car lights barely visible behind a wall of thick white smoke and scattered debris, its tires screeching and spinning wildly – a scene punctuated by the sounds of a fire alarm and screams for help. Nadia, unable to stand, was carried away by two hospital employees. A nurse grabbed 3-year-old Rio.

“With the injuries that were sustained from this, hospital staff is working through it,” said an emergency responder over the radio, according to a recording. “But it’s probably going to overload the ER here.”

Regaining consciousness, Levi realized their youngest, Sunny – months shy of his second birthday – was missing. Levi was soaking wet, bloody and going off adrenaline.

‘You heard screaming’: Witnesses describe scene after car crashes into ER

“I went to go turn off the car because I couldn’t see him anywhere,” Levi said. “And when I leaned in to go turn off the car, he was like on the floor with trash and debris, covered in blood. I just saw the whites of his eyes looking up at me.”

The impact sent Sunny through the car’s windshield. Levi found his son lying in the passenger footwell.

“I kept asking, ‘What’s going on with Sunny? What’s going on with Sunny? What’s going on?’” Nadia said she remembered before being placed into an ambulance and transported to St. David’s Round Rock Medical Center. “And the doctor was like, ‘He’s screaming. You hear him? That’s a good sign.’”

The car’s driver died. At least five people were injured, including all four members of the Bernard family.

In an exclusive interview three months after a car ran them over, the two parents spoke publicly for the first time about their ordeal. The family is struggling – not just with the pain but with comprehending what happened that day.

“That’s my worst nightmare, right?” Levi said. “Being there and watching your whole family get taken out by a vehicle and (there’s) like literally not a thing you can do to stop it.”

Video taken by the family at the hospital the next morning shows Sunny crying with hundreds of stitches all over his face and head. The toddler suffered a broken nose and jaw in addition to bone-deep lacerations to his scalp, face, leg and stomach. He’s had multiple surgical procedures and is being monitored for a brain injury, the family said.

Nadia, an Austin real estate agent, has not been able to work since the accident. She was hospitalized for almost a month and is still in a wheelchair recovering from a broken shin that required two surgical procedures. She also suffered broken ribs, a broken shoulder, nerve damage and a cut on her cheek so deep it required surgery, she said. It will take months to heal.

Levi’s ankle was injured and, months later, his elbow is still swollen to the size of a golf ball. He suffered lacerations to the back of his head and lost his sense of taste and smell for weeks after the accident, he said.

Rio needed nine stitches to close a gash on his left palm. Surgery removed a shard of glass buried in his arm.

“Everything’s in question marks, you know?” Nadia said. “Like, why did this happen to us? Why did we survive this?”

WATCH: Levi and Nadia Bernard speak in an exclusive, extended interview with KXAN investigators.

Austin police are still investigating the incident and the exact cause of death. At the time, authorities said there was “no indication” this was intentional nor that the driver “suffered from a medical episode.”

“There is no new information available for release at this time,” said Austin Police on April 16, more than two months later, when asked for an update.

To better understand what happened, KXAN requested police body camera footage and the 911 calls from that day. In a letter, authorities said releasing that would “interfere” with “an open or pending criminal matter.” The crash report is heavily redacted and only reveals what happened, not why: “a mass casualty incident” caused by “a vehicle crashing through the doors of the ER lobby.”

Less than 24 hours after the fatal crash, the chief medical officer for St. David’s North held a news conference where he thanked God for the same lobby fish tank that had attracted the Bernard family.

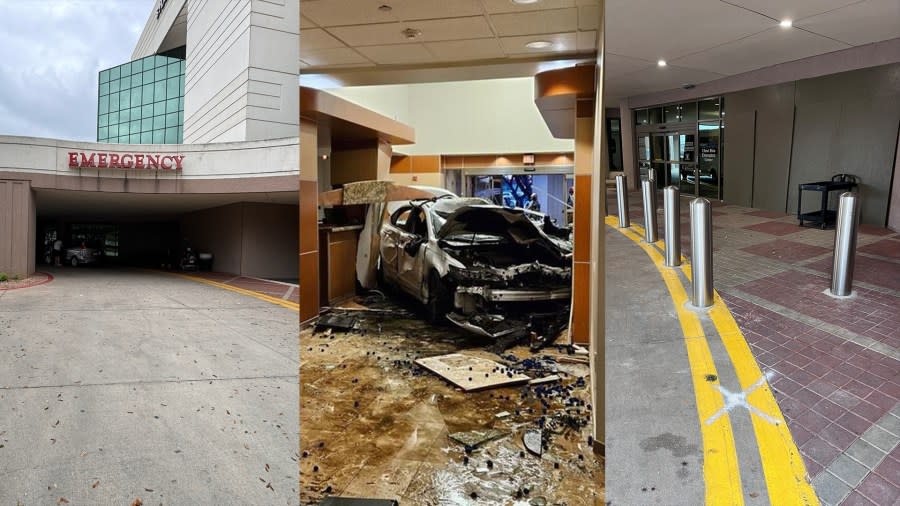

“We really felt, considering the tragic nature of what happened, there was so many blessings that did occur,” Dr. Peter DeYoung told reporters. “Something that might be seen in some of the videos was the water. The vehicle had a direct impact to a very large aquarium that, really, I believe, saved lives as it absorbed the impact.”

“I thank God for intervening there and giving us that protection,” he added.

Still, experts say features specifically designed for safety might have prevented a crash like this from happening. They are called bollards – security barriers – essentially shorter, thick, vertical steel poles. They are often found in front of stores, stadiums and government buildings to stop vehicles from driving into them, either from an attack or accidentally.

St. David’s North Austin Medical Center did not have them at its emergency room entrance.

“We do not have a barrier there,” DeYoung told reporters the day after the crash. “That is open to make ease of access for patients to come in with wheelchairs and other assist devices.”

It’s unclear why that decision was made since bollards can be spaced far enough apart to allow wheelchairs and gurneys to pass through them, but not cars. St. David’s also had bollards outside emergency rooms at some of its other area hospitals and used them to safeguard outdoor equipment at its north Austin location, as seen in photos taken by the family’s attorney.

St. David’s North Austin Medical Center did not have bollards when a sedan drove into the ER. (Courtesy Howry, Breen & Herman) St. David’s North Austin Medical Center did have bollards protecting equipment (Courtesy Howry, Breen & Herman) St. David’s North Austin Medical Center did have bollards protecting equipment (Courtesy Howry, Breen & Herman)

Several other hospitals across Central Texas also lack bollards. Over several days, KXAN investigators visited 34 major area hospitals with emergency rooms.

We found 18 hospitals had bollards, nine had partial coverage and seven had none.

Austin

✕

Ascension Seton Medical Center Austin

1201 W. 38th St.

Bollards: Partial (only valet)Ascension Seton Northwest Hospital

1113 Research Blvd.

Bollards: PartialAscension Seton Southwest Hospital

7900 FM Rd. 1826

Bollards: YesBaylor Scott & White Medical Center – Austin

5245 W US 290

Bollards: YesCentral Texas Rehabilitation Hospital

700 W. 45th St.

Bollards: YesCornerstone Specialty Hospitals Austin

4207 Burnet Rd.

Bollards: YesDell Children’s Medical Center

4900 Mueller Blvd.

Bollards: YesDell Seton Medical Center at The University of Texas

1500 Red River St.

Bollards: YesHeart Hospital of Austin (Saint David’s)

3801 N. Lamar

Bollards: PartialSaint David’s Children’s Hospital

12221 N. Mopac

Bollards: YesSaint David’s North Austin Medical Center

12221 N. Mopac

Bollards: YesSaint David’s South Austin Medical Center

901 W. Ben White

Bollards: YesSt. David’s Medical Center

919 E. 32nd St.

Bollards: YesSaint David’s Rehabilitation Hospital

1005 E. 32nd St.

Bollards: Partial

Bastrop

✕

Ascension Seton Bastrop Hospital

630 State Hwy. 71 W.

Bollards: Yes

Buda

✕

Baylor Scott & White Medical Center

5330 Overpass

Bollards: YesAscension Medical Group Seton Health Center

5235 Overpass Rd.

Bollards: Yes

Burnet

✕

Seton Highland Lakes

3201 S. Water St.

Bollards: Partial

Cedar Park

✕

Cedar Park Regional Medical Center

1401 Medical Pkwy.

Bollards: No

Fredericksburg

✕

Hill County Memorial Hospital

1020 S. State Hwy 16

Bollards: No

Georgetown

✕

Saint David’s Georgetown Hospital

2000 Scenic Dr.

Bollards: Partial

Kyle

✕

Ascension Seton Hays

6001 Kyle Pkwy.

Bollards: Partial (large round concrete barriers/widely spaced out, car could fit through)

Lakeway

✕

Baylor Scott & White Medical Center

100 Medical Pkwy.

Bollards: Yes

Marble Falls

✕

Baylor Scott & White Marble Falls

810 State Hwy. 71

Bollards: Partial

Pflugerville

✕

Baylor Scott & White Medical Center

2600 E. Pflugerville Pkwy.

Bollards: Partial

Round Rock

✕

Saint David’s Round Rock Medical Center

2400 Round Rock Ave.

Bollards: No (bollards around one post)Baylor Scott & White Medical Center

300 Univeristy Blvd.

Bollards: No (very vulnerable)PAM Health Rehabilitation Hospital of Round Rock (Seton)

351 Seton Pkwy.

Bollards: YesSt. David’s Oakwood Surgery Center

16030 Park Valley Dr. Suite 100

Bollards: YesSt. David’s Round Rock Medical Center / Surgery Center Women’s Center

2400 Round Rock Ave.

Bollards: Yes

San Marcos

✕

Christus Santa Rosa Hospital

1301 Wonder World Dr.

Bollards: No, but ER has long walkway to doors/main entrance exposed

Smithville

✕

Ascension Seton Smithville

1201 Hill Rd.

Bollards: Yes

Taylor

✕

Baylor Scott & White Medical Center

403 Mallard Ln.

Bollards: No

West Lake Hills

✕

The Hospital at Westlake Medical Center

5656 Bee Cave Rd.

Bollards: No

KXAN investigators traveled to 34 major Austin-area hospitals between March 28 – April 1, 2024, to see if security barriers – or bollards – were installed at entrances. Touch the red circles for locations and their results in each city. (KXAN Interactive/Robert Sims, Christina Staggs)

Most of the hospitals referenced in KXAN’s investigation, including St. David’s, did not answer questions about security barriers.

“The health and safety of our patients, visitors and staff continues to be the highest priority for our healthcare systems,” read a joint statement from St. David’s HealthCare, Ascension Seton and Baylor Scott & White Health.

Baylor Scott & White Medical Center-Round Rock does not have bollards in front of its entrance (Courtesy Howry, Breen & Herman) Baylor Scott & White Medical Center-Round Rock does not have bollards in front of its entrance (Courtesy Howry, Breen & Herman) Baylor Scott & White Medical Center-Round Rock does use bollards in front of a sidewalk and current construction area adjacent to its entrance (Courtesy Howry, Breen & Herman) Baylor Scott & White Medical Center-Buda has bollards in front of its main entrance (KXAN Photo/Matt Grant) Baylor Scott & White Medical Center-Buda entrance without bollards (KXAN photo/Matt Grant) Cedar Park Regional Medical Center recently began installing bollards after KXAN reached out to ask why it was not using them (Courtesy Howry, Breen & Herman) Before it began installing bollards at its entrance, Cedar Park Regional Medical Center did use bollards to protect what appears to be a water pipe (Courtesy Howry, Breen & Herman) St. David’s Medical Center on E. 32nd Street in Austin uses bollards. (KXAN Photo/Matt Grant) St. David’s Medical Center on E. 32nd Street in Austin uses bollards. (KXAN Photo/Matt Grant) St. David’s Oakwood Surgery Center-Round Rock uses bollards (KXAN Photo/Matt Grant) Ascension Seton Bastrop Hospital has bollards in front of its ER (KXAN Photo/Matt Grant) Ascension Medical Group Seton Health Center Buda has bollards in front of its entrance (KXAN Photo/Matt Grant) Ascension Seton Smithville Hospital uses bollards (KXAN Photo/Matt Grant) Ascension Seton Smithville Hospital uses bollards (KXAN Photo/Matt Grant) Ascension Seton Smithville Hospital uses bollards (KXAN Photo/Matt Grant) Dell Seton Medical Center at The University of Texas uses bollards (KXAN Photo/Matt Grant) Dell Seton Medical Center at The University of Texas uses bollards (KXAN Photo/Matt Grant) Dell Seton Medical Center at The University of Texas uses bollards (KXAN Photo/Matt Grant)

The joint statement focused on the “safety protocols in place” like “24/7 extra security patrol, “enhanced exterior lighting” and “training for all staff” – even though we asked St. David’s specifically about why it didn’t have bollards at its north Austin site.

See the full statements from St. David’s and other hospitals that responded to our questions

There are no state or federal legal requirements, or even industry standards, for hospitals to have bollards, according to industry experts and organizations that help develop voluntary building codes.

“The reality is these accidents are frequent,” said Rob Reiter, co-founder of the Storefront Safety Council and expert in vehicle-into-building crashes. “They are foreseeable. And they are preventable.”

Using lawsuits, media and police reports, SSC developed a nationwide database of vehicle accidents involving a building, which includes medical facilities.

It shows at least 244 crashes into medical facilities since 2014. At least 30 were fatal.

“I can tell you with confidence that none of them that were protected by bollards are in my statistics because they would not have penetrated into the building past the bollards,” Reiter said. “That’s the beauty of having a solution that actually solves the issue.”

Reiter acknowledges the statistics are likely higher than what his group has pieced together.

SSC’s database showed, in the last decade, at least a dozen crashes into medical facilities in Texas. KXAN’s own analysis of data compiled in that same timeframe from the Texas Department of Transportation Crash Records Information System found at least 85 additional vehicle crashes involving medical facilities statewide.

Watch: Texas-tested security barrier could prevent ER crash disaster

Combined, the two datasets reveal nearly 330 crashes nationwide since 2014.

Neither dataset includes two east Texas crashes in January when vehicles drove into two Baylor Scott & White medical centers in Navasota and College Station.

The recent fatal crash at St. David’s North had the most victims in Texas in that timeframe, according to TxDOT data.

Map of crashes that have occurred in Texas involving medical facilities or hospitals in the last 10 years. Source: Texas Department of Transportation (KXAN Interactive/Dalton Huey)

“They keep happening, and they happen for the same reasons,” Reiter said. “They’re predictable.”

He knows firsthand. In 2016, he was involved with the process to install steel bollards in Times Square. Less than a year later, he credited them with saving lives when a driver barreled into a crowd of people, killing one person and injuring 22 others. In response, city officials pledged to roll out 1,500 new bollards in public spots to underscore its “resolve in keeping New York City safe from future attacks.”

Reiter began tracking storefront crashes 20 years ago after working in security and noticing how common they were. He said there are “added risk factors” when it comes to medical facilities – like patients driving up close to an ER entrance on medication or in distress – that make these types of crashes more likely to occur when bollards are not present.

“So, you have increased risk, by virtue of drivers who are not in the best of condition at the time they’re approaching,” Reiter said. “And, if you have set people up to be aimed at your door because that’s where you want them to come, don’t be surprised if vehicles, from time to time, don’t stop.”

Working with news partners in other states, KXAN documented at least a half dozen similar crashes – including some law enforcement say were intentional – at hospital emergency rooms in recent years. Vehicles have rammed into ERs in Florida, Massachusetts and two cases in Connecticut that were days apart.

In 2018, a man was accused of crashing a car carrying several cans of gasoline into the emergency entrance of Middlesex Hospital in Middletown, Connecticut, and setting himself on fire, according to officials. (Courtesy NBC Connecticut) After the fire is put out, a vehicle is visible inside the ER doors at Middlesex Hospital in Middletown, Connecticut. (Courtesy NBC Connecticut) In April 2023, a woman crashed her SUV into HCA Florida Osceola Hospital. (Courtesy WESH/Kissimmee Police) On Jan. 3, 2024, a patient drove into the lobby waiting room at Baylor Scott & White Clinic-Navasota. (Courtesy Navasota Examiner) On Jan. 3, 2024, a patient drove into the lobby waiting room at Baylor Scott & White Clinic-Navasota. (Courtesy Navasota Examiner) In January 2023, a car drove into the the emergency waiting room at Emory Hillandale Hospital in Lithonia, Georgia. (Courtesy 11Alive) Surveillance video shows an SUV through the ER entrance at Piedmont Hospital in Atlanta in June 2020. One person died and four others were injured. (Courtesy 11Alive) Kailyn Bailey, left, is seen in surveillance video moments after being hit by an SUV. (Courtesy 11Alive) In 2017, a vehicle struck the outside of the ER at Newton-Wellesley Hospital in Newton, Massachusetts. (Courtesy NBC 10 Boston) In 2018, a car struck and shattered a window at Hartford Hospital. (Courtesy NBC Connecticut) In 2017, before it was torn down, the driver of a stolen car crashed into a barricade outside the University Medical Center Brackenridge in Austin. (Courtesy KXAN file/Austin Fire Info)

SLIDESHOW: KXAN investigators located and compiled visual evidence of at least a half dozen similar incidents at hospital ERs in other states since 2017.

In 2018, authorities said a man intentionally crashed his car carrying several cans of gasoline into an emergency room entrance in Middletown, Connecticut, causing a fiery scene. The driver later died from his injuries. In the Florida case, police body camera video shows an SUV inside the hospital entrance. Moments before the crash, a witness said the driver yelled, ‘Sir, would you move? I’m going to drive my car inside.’”

In the past four years, there were at least two incidents in Georgia, including one at Piedmont Hospital in Atlanta in 2020 that was fatal.

Map of crashes involving medical facilities and hospitals nationwide in the last 10 years. Source: Storefront Safety Council (KXAN Interactive/Dalton Huey)

In that incident, it was reported a 55-year-old woman died and four others were injured when another woman “lost control” of her vehicle and drove into the patient entrance, hitting several people.

The widower of a woman who died in that crash sued the hospital for its “failure to provide bollards or other barriers to protect … outside the emergency department.” The case was settled for an undisclosed amount of money, according to the attorney who filed the lawsuit and court filings.

A separate lawsuit, filed by Kailyn Bailey who was injured in the same incident, also blamed the hospital for its “failure to provide bollards.”

“How do you drive through a hospital, critically injure me, kill one person?” Bailey asked in an interview.

That suit was dismissed on procedural grounds, filings show. The law firm handling the case did not respond to KXAN’s multiple attempts for comment.

Multiple calls, voicemails and emails to a Piedmont spokesperson were not returned.

Texas-tested security barriers could prevent ER crash disaster

KXAN witnessed firsthand how certain bollards can effectively stop the equivalent of a Dodge Ram pickup truck traveling at 20 mph. In April, the McCue Corporation commissioned two crash tests. They took place at the Texas A&M Transportation Institute near College Station. One type, designed for traffic control and made of concrete, snapped. The other, a crash-test-rated bollard made of high-strength steel, absorbed the impact.

While crash-test-rated bollards have proven to be effective, they are also expensive. It would cost a hospital upwards of $30,000, for example, to install 20 crash-rated bollards, according to McCue. The company has been in the bollard business for more than 35 years and sells its products all over the world, including to H-E-B.

The decision not to install them can also be a costly one, the company said, describing unguarded facilities as “a ticking time bomb.”

“I don’t think it’s a problem for them to find the funds,” said McCue CEO David DiAntonio. “I think it’s more educating them and, unfortunately, it does take this type of accident to get people educated.”

WATCH: An animation used in the 7-Eleven lawsuit shows how the 2017 crash occurred and how bollards could have prevented it. (Courtesy DK Global/Power Rogers LLP)

Last year, a Chicago law firm announced a $91 million settlement against 7-Eleven, which is headquartered in Irving, Texas. The settlement stems from an incident in 2017, when a driver struck another person outside an Illinois store, hitting the gas instead of the brakes while trying to park. The victim was pinned against the store and, as a result, had to have a double amputation of his legs above the knees.

In the lawsuit, 7-Eleven was forced to turn over 15 years’ worth of crash data. It revealed there had been more than 6,253 storefront crashes at its locations across the country between 2003 and 2017 – averaging more than one a day.

“As long as 7-Eleven refuses to place bollards in front of its stores to prevent these crashes, people will continue to be seriously injured or killed,” attorney Joe Power said in a news release.

“This problem can no longer be ignored,” he added.

KXAN’s sharing its ER security barrier findings with Texas lawmakers

Multiple requests to 7-Eleven seeking comment were not returned.

Asked what it would take, besides litigation, to require bollards be installed in front of vulnerable entrances at critical infrastructure, DiAntonio had a simple answer with an uncertain path: “In the state, the legislature would have to put a law in.”

More than 100,000 bills have been filed in Texas since 1993. None had proposed rules about bollards, a KXAN analysis found.

Emotional promises from Austin leaders after hospital safety report

“Can somebody get me a tissue?” Austin City Council Member Mackenzie Kelly asked as a tear ran down her cheek. “Sorry.”

The emotional reaction came in the middle of watching a KXAN investigation into the deadly crash at St. David’s North Austin Medical Center, which revealed the type of incident that occurred there on Feb. 13 has happened more than 300 times across the country in the last decade.

“Generally, there’s added risk factors at medical facilities,” said Storefront Safety Council co-founder Rob Reiter, an expert who tracks vehicle-into-building crashes. “Because you have drivers that might be on medication, you have drivers that might be in distress, they could be injured, they could be suffering a medical emergency … and if you have set people up to be aimed at your door — because that’s where you want them to come — don’t be surprised if vehicles from time to time don’t stop.”

The number increases to 28,014 if you look at crashes the SSC has tracked with any storefront, not just hospitals, since 2014.

Most hospitals KXAN visited in Central Texas used vertical security posts, called bollards, at their entrances. St. David’s did not have them at its north Austin location on the day of the crash, a KXAN investigation found. The hospital installed seven afterward. A spokesperson would not answer questions about its use of bollards, citing security reasons.

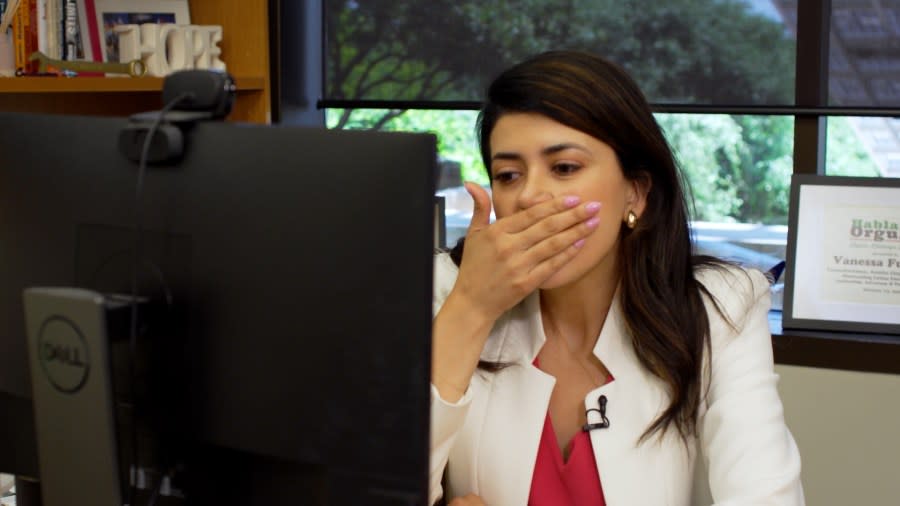

KXAN sent our investigation to more than 50 state lawmakers and every Austin City Council member. Council Members Kelly and Vanessa Fuentes were quick to respond — and wanted to see what we uncovered.

WATCH: See the KXAN investigation that sparked local leaders to act

“How do we prevent this from continuing to happen?” Kelly asked, after pausing the KXAN report and turning to her staff.

“Can we initiate an ordinance change that requires any new builds of hospitals, or places where people seek medical attention to have these types of protections?” she asked, referring to the steel posts designed to prevent vehicles from crashing into buildings or people.

A former volunteer firefighter who worked in health care, Kelly called bollards “a very easy fix” that can save lives. The McCue Corporation, which makes bollards for companies across the country, including H-E-B, said it would cost around $30,000 to install 20 crash-rated bollards at a hospital entrance.

Nadia and Levi Bernard were inside the lobby at St. David’s North Austin Medical Center looking at an aquarium with their two toddlers when a white Acura barreled through it, injuring them all. Nadia is still in a wheelchair. Their 2-year-old son has hundreds of stitches in his head and is being monitored for a brain injury.

The family hired an attorney and are expected to file a lawsuit against St. David’s related to not having bollards in place at the time.

Police are still investigating the crash, which killed the driver.

“The safety of our patients and their families, as well as our employees and visitors, is always our top priority,” said St. David’s HealthCare in a statement previously, adding that per policy, “we do not comment on pending claims or litigation.”

Asked about potential policy changes, St. David’s HealthCare said it “will work with policymakers and officials to ensure compliance with any new laws if they are passed.”

KXAN asked Kelly what she would say to the Bernard family.

“Your tragedy, hopefully, will save other lives and prevent that from occurring (again),” Kelly said. “But, there is no excuse for the pain your family has felt, and I wish I could give you all big hugs.”

Late Wednesday, Kelly publicly credited KXAN’s investigation and said she intends to introduce a resolution for consideration on the July 18 council meeting agenda. Kelly said she wants to “direct the City Manager to make all necessary and appropriate amendments to City Code requiring safety barriers, known as bollards, to be constructed at any new medical facility within the City’s jurisdiction.”

“Many of you may have seen the recent investigative report by KXAN highlighting the frequency of automobile crashes into medical facilities like hospitals and emergency rooms, across the state and country,” Kelly wrote on the City of Austin Council Message Board.

She asked for co-sponsors to her resolution, calling this an “important matter of public safety in our community.”

“Oh my gosh,” Council Member Fuentes said as she watched KXAN’s report, at one point putting her hand over her mouth in shock. “Wow.”

“Thank you all for covering this,” she said afterward. “I appreciate you all doing this type of investigative journalism because that exactly … is why we need policies updated.”

Fuentes called what happened at St. David’s “heartbreaking.” Now, she also wants to require bollards, but not just at hospitals.

“We want all of our hospital systems, all of our critical infrastructure, our nursing facilities, anywhere where there’s a lot of people moving in and out of,” Fuentes said, “We need to start looking at how are they designing their buildings with safety in mind.”

Asked if she would look into changes to address that, Fuentes quickly responded: “Yes.”

“We’re looking at a potential zoning change, any update to our land development code, any type of regulation where it makes sense that the city could really ensure that we have these safety measures in place,” Fuentes said. “And, to me, that’s what local government is all about, is ensuring the safety of our communities.”

KXAN also asked Fuentes what she would say to the Bernard family.

“I’m so sorry for the horrific experience that you’ve had, knowing that their children were injured, that the family was injured themselves … it’s just horrifying,” she said. “I hope that by us taking action, by bringing forward a policy that seeks to ensure this never happens again here in Austin, that that brings some semblance of relief for them knowing that their experience, their horrific experience, has not gone without any action being taken to prevent it.”

WATCH: Crash-testing bollards at Texas A&M Transportation Institute

Current city policy “does not prohibit hospitals or other businesses from installing bollards,” a City of Austin spokesperson said after KXAN asked the city manager for a comment. Any new policies or requirements “wouldn’t impact current facilities, only future ones” and would require a transportation code change if bollards are placed in a right-of-way, the spokesperson added.

The Austin Transportation and Public Works Department said its focus is on the public right-of-way and anything to do with installing bollards on private property, like ER entrances, is not within its “typical purview.” The city is “generally supportive of initiatives which increases safety related to motor vehicle crashes,” a spokesperson added.

The Austin Code Department suggested KXAN contact other agencies that work with public safety saying they “may have more insight or relevant information regarding this issue.”

KXAN also reached out to Austin Mayor Kirk Watson. A spokesperson said they would “review this” with the mayor. We will update this story with any additional responses we receive.

Austin wouldn’t be the first place to consider policies surrounding safety barriers.

A Flourish map showing some cities with safety barrier ordinances. Source: Storefront Safety Council (KXAN Interactive/Dalton Huey)

Over the past decade, the SSC has worked to help pass local ordinances requiring crash-rated “vehicle impact protection devices,” like bollards, in business parking lots in five cities and counties. Some specifically addressed protecting outdoor public seating areas. Three were sparked by deadly accidents:

A 6-year-old was killed in a crash at a dentist’s office in Midfield, Alabama, in 2017.

A 73-year-old was killed in a crash at an ice cream shop in Artesia, California, in 2014

A 4-year-old was killed in a crash at a daycare center in Orange County, Florida, in 2014.

The SSC helped local policymakers with ordinance language requiring the bollards be crash-rated to the same standards used during tests KXAN watched at the Texas A&M Transportation Institute. The language also made sure they comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act.

“Experts in vehicle-into-building crashes indicate that standard parking lot wheel stops and raised sidewalks are not sufficient, by themselves, to stop the force of a vehicle in such pedal error accidents and that other design standards and devices are needed to protect pedestrians, shoppers and customers,” read part of one ordinance in Artesia, California, the SSC helped develop following a deadly crash at an ice cream shop in 2014.

In 2022, the state of California updated a law allowing insurance companies to offer discounts to businesses that install vehicle safety barriers “to protect pedestrians” from motor vehicle collisions.

Both Kelly and Fuentes’ offices have already reached out to the SSC in response to a KXAN investigation. Fuentes’ staff told Reiter they want to “collaborate on a policy in Austin” and are interested in “putting forth policy to require safety devices in front of hospitals and businesses to prevent crashes,” according to an email shared with KXAN.

Following the crash at St. David’s North Austin Medical Center, KXAN visited 34 major hospitals with emergency rooms in Central Texas. We found 18 hospitals had bollards, nine had partial coverage and seven had none. In Austin, four had partial coverage.

Most of the hospitals KXAN visited in the Austin area were owned by St. David’s HealthCare, Ascension Seton or Baylor Scott & White Health. We reached out to each hospital group about potential policy changes that could require bollards.

“Ascension Seton works with policymakers on various issues regarding the health and safety of our employees, patients and their families,” Ascension Seton said in a statement. “We will work with officials to ensure compliance with any new laws.”

“The health and safety of our patients, visitors and staff continues to be the highest priority for our health care system,” Baylor Scott & White Health said in a statement. “We appreciate the continued conversation on safety measures and welcome the opportunity to collaborate with lawmakers.”

Weeks before the crash at St. David’s North Austin Medical Center, vehicles drove into two Baylor Scott & White medical centers in Navasota and College Station.

Fuentes said she wants to see “uniform regulations” at the state level when it comes to bollards.

In the past three decades, Texas lawmakers have filed more than 101,000 bills, according to the Legislative Reference Library. While many dealt with public safety, a review of those bills found none appeared to have ever proposed rules regarding bollards outside buildings, a KXAN investigation found.

That could change in the next legislative session.

KXAN reached out to more than 50 state lawmakers who sit on transportation or health-related committees or represent districts with prior crashes involving medical centers.

In the week since our first report, more than a half dozen lawmakers have responded and indicated this is an issue they want to look into during the next legislative session:

The chief of staff for Sen. Sarah Eckhardt, D-Austin, who sits on the Senate Committee on Transportation, told KXAN: “We have put this issue on our legislative ideas to research.”

The joint chief of staff for Rep. Donna Howard, D-Austin, told KXAN their office is “reviewing materials and doing some research of our own too.”

A senior adviser to Rep. James Talarico, D-Austin, said their office will “further review” our findings. “We appreciate all your work producing such a thorough investigation and for focusing on this important issue,” Talarico’s adviser said.

Aides to Sen. Borris Miles, D-Houston, asked to see our data.

The chief of staff for Rep. Venton Jones, D-Dallas told KXAN, “Thank you for bringing this to our attention” and said he would discuss it with the representative.

Aides to Sen. Royce West, D-Dallas, are looking into our findings.

In the last legislative session, Sen. Bob Hall, R-Edgewood, invited investigator Matt Grant to testify in front of the Senate Committee on Health and Human Services about a KXAN investigation into the Texas Medical Board. Hall co-sponsored a bill, which became law, to reform the TMB based on our findings. Now, in response to our investigation into hospital safety, his chief of staff said she will “visit with the Senator on this idea.”

KXAN also reached out to several state and national organizations that represent healthcare workers.

The Texas Health and Human Services Commission, which regulates health care facilities “has no plans at this time to make rule changes that would require bollards at hospitals,” HHSC spokeswoman Jennifer Ruffcorn said.

The Texas Medical Association has no policies regarding bollards and, therefore, has “no formal position” for or against them.

“Naturally our physician members want patients to be safe and healthy,” TMA spokesman Brent Annear said, “especially in places to which they go for health care and healing.”

The Texas Hospital Association and Capital Area of Texas Regional Advisory Council did not respond to our latest requests for comment. Gov. Greg Abbott’s office also did not respond. The American Hospital Association declined to comment. We will update this story with any statements we receive.

The Texas Nurses Association previously said it encourages all healthcare organizations to “seek evidence-based protocols and procedures that create a safe environment for their staff and patients.”

“Texas Nurses Association supports efforts to research risks to medical facility staff and patients,” the TNA said in a new statement. “It is important to identify top risks and alleviate those risks.”

The Austin EMS Association, which represents more than 500 emergency medical services professionals, previously called bollards a “cost-effective” security measure and said they “could have helped” if they had been in place at St. David’s North Austin Medical Center on the day of the fatal crash.

“I do think that this event will potentially change some infrastructure for a lot of the hospitals in the area,” Austin EMS Association President Selena Xie previously said.

KXAN asked Xie what she thought of potential measures to require bollards at hospitals.

“We don’t have any specific thoughts besides supporting them,” she said.

On Wednesday, the Bernard family reacted to Kelly and Fuentes’ calls for new measures to improve hospital security.

“Nadia cried when she heard that news that lawmakers are taking this seriously,” Levi told KXAN in an email. “[A]mazing how quickly your story is getting attention.”

Injured family files lawsuit in fatal Austin hospital crash

AUSTIN (KXAN) – Just over a week after speaking out publicly for the first time in an exclusive KXAN investigation, a family of four seriously hurt in February’s deadly car crash at an Austin hospital is suing.

EXPLORE: KXAN’s “Preventing Disaster” investigation

The Bernard family filed a 25-page lawsuit, which was first reported by KXAN, in Travis County against St. David’s HealthCare early Thursday morning. The lawsuit seeks more than $1 million for mounting medical bills, pain and suffering and lost wages. Their attorney said what happened to them should have been prevented.

Project Summary:

This story is part of KXAN’s “Preventing Disaster” investigation, which initially published on May 15, 2024. The project follows a fatal car crash into an Austin hospital’s emergency room earlier that year. Our team took a broader look at safety concerns with that crash and hundreds of others across the nation – including whether medical sites had security barriers – known as bollards – at their entrances. Experts say those could stop crashes from happening.

“Plaintiffs have filed this case to encourage St. David’s and all hospitals to quit waiting for accidents to happen and construct safety barriers now at their emergency rooms before more people are hurt by vehicle intrusions, a very common incident,” the lawsuit stated.

WATCH: Levi and Nadia Bernard speak in an exclusive, extended interview with KXAN investigators.

In recent days, when asked about the lawsuit the family was planning to file, St. David’s acknowledged, “the safety of our patients and their families, as well as our employees and visitors, is always our top priority.” Citing hospital policy, it would “not comment on pending claims or litigation.”

KXAN sent St. David’s a copy of the lawsuit after it was filed Thursday morning. Asked again for comment, St. David’s reiterated the same statement.

“For my clients, the fact that this happened to them is completely unacceptable,” said Austin trial attorney Sean Breen, who represents the Bernard family, with the law firm Howry, Breen & Herman. “They’re still dealing with it. It was totally unnecessary. It was totally preventable. And, what they really, really want is for nobody else to have to go through what they’ve gone through.”

It’s been more than three months since Nadia Bernard, her husband Levi, and their two toddlers were inside the lobby of St. David’s North Austin Medical Center looking at a fish tank. The car hit the tank and the family.

The driver of the vehicle, Michelle Holloway, died.

The Austin Police Department is still investigating the cause of the crash but previously said it wasn’t intentional. The lawsuit alleges Holloway arrived at the hospital with her niece to visit a sick family member. According to the lawsuit, Holloway, a passenger, was asked to move the 2016 white Acura TLX, which was parked at the hospital’s north entrance. The lawsuit alleges Holloway was “unfamiliar” with the car and “accidentally lost control,” crashing into the “vulnerable and unprotected” ER entrance and into the lobby, running over and seriously injuring all four members of the Bernard family.

“The police investigation into the crash is ongoing and contingent on (Holloway’s) pending autopsy and toxicology results,” APD said in a statement Thursday.

The crash report is heavily redacted. It categorizes what happened as an aggravated assault with a motor vehicle and only reveals what happened, not why: “a mass casualty incident” caused by “a vehicle crashing through the doors of the ER lobby.”

READ: Hospitals respond to KXAN’s “Preventing Disaster” investigation

“I think I still (have) not super processed … everything,” said Nadia, tearing up and still in a wheelchair recovering from a broken leg. “I think I’m still very much not sure what to think of it.”

Cell phone video taken moments after the crash shows Nadia unable to stand, being carried away.

Their youngest son, 2-year-old Sunny, needed hundreds of stitches around his face and head and is being monitored for a brain injury after going through the car’s windshield. His dad found him in the passenger footwell.

Levi’s previous descriptions to KXAN were quoted in the lawsuit, including when he described the situation as his “worst nightmare … watching your whole family get taken out by a vehicle and (there’s) like literally not a thing you can do to stop it” and when he recalled thinking: “This is what dying feels like.”

Back in his office, Breen opened a cardboard box and showed KXAN investigators the large, thick shards of glass and granite found inside the white Acura after it had been towed away.

“This is where they found little Sunny laying on this,” he said, showing a heavy piece of glass from the aquarium.

“Why did it happen to us?” Nadia asked. “Why did we survive this?”

In the lawsuit, the Bernard family and their attorney accuse St. David’s of “gross negligence” for failing to take safety precautions used “around the country, around the state, around the city and in some of St. David’s other facilities.” The lawsuit points to the hospital’s lack of vertical security posts, called bollards, which were installed after the Feb. 13 crash and has been the focus of an ongoing KXAN investigation.

“Had St. David’s installed those safety bollards before this incident, as a reasonable hospital should have, this incident would have been totally harmless,” the lawsuit said. “St. David’s cannot profess ignorance of either the dangerous condition or the solution.”

St. David’s did not answer our questions about its bollards saying it “cannot disclose specific details of our security measures.”

The lawsuit criticizes St. David’s, a $2.1 billion hospital system, for announcing $953 million worth of “healthcare infrastructure” investments in a news release in 2022, but not spending “a very small fraction” of that money on bollards at vulnerable ER entrances. The lawsuit said organizations, like the International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety, have called for “physical barrier protection for emergency rooms” since at least 2012.

KXAN investigates recently traveled to Texas A&M’s Transportation Institute near College Station to see, firsthand, how effective crash-rated bollards can be at stopping the equivalent of a Dodge Ram pickup truck going 20 miles per hour. At the time of the crash, St. David’s, instead, credited the large lobby fish tank for absorbing the impact and saving lives.

“I thank God for intervening there and giving us that protection,” St. David’s North Chief Medical Officer Dr. Peter DeYoung said on Feb. 14, less than 24 hours after the crash.

“I wish it was thanking God that there were bollards in front of the building,” Levi countered. “Not the thing that attracted us to the center of the lobby.”

The lawsuit called DeYoung’s remarks “both cruel and damning.”

This isn’t the first time a hospital has been sued over its lack of bollards. A KXAN investigation found Piedmont Hospital in Atlanta was sued in 2020, and settled for an undisclosed amount, following a similar deadly crash at its ER. Piedmont did not respond to our multiple requests for comment.

The Storefront Safety Council, which tracks building crashes, and a KXAN analysis of TxDOT data, revealed more than 300 crashes at medical facilities nationwide in the past decade, including at least 85 in Texas – a fact referenced in the lawsuit.

Two Austin City Council members

Two Austin City Council members have already reached out to the SSC, in direct response to KXAN’s investigation, wanting to collaborate on an ordinance that would require bollards at Austin hospitals.

“The reality is these accidents are frequent,” said Rob Reiter, SSC co-founder and expert in vehicle-into-building crashes. “They are foreseeable. And they are preventable.”

Breen agrees and believes a jury will, too.

“Oh, this is 100% preventable,” he said. “On the scale of accidents that don’t need to happen, this is a 10 all right. Why? Because you have a known problem that’s easy to predict. You know it’s going to happen. It’s cheap to prevent. Why not do that? Why wait until someone is destroyed before you actually act?”

KXAN Investigative Photojournalist Chris Nelson, Graphic Artist Wendy Gonzalez, Director of Investigations & Innovation Josh Hinkle, Investigative Producer Dalton Huey and Digital Director Kate Winkle contributed to this report.

Copyright 2024 Nexstar Media, Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed.

For the latest news, weather, sports, and streaming video, head to KXAN Austin.