Stadium tax strikes out, thwarting plans for KC Royals stadium in the Crossroads. What now?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Downtown baseball might still be in Kansas City’s future, but the prospect of that happening in time for the 2028 season, as the Royals had hoped, suffered a devastating blow on Tuesday.

Question 1 lost by a wide margin.

Jackson County voters rejected a 40-year sales tax that would have helped pay for construction of a Royals ballpark immediately south of the downtown freeway loop in the East Crossroads and a major renovation of Arrowhead Stadium for the Chiefs.

The ballot measure failed 58% to 42%, and was trounced in both eastern Jackson County and in Kansas City south of the Missouri River. In total, 56,606 voted yes, and 78,352 voted no.

In his concession speech, Royals majority owner John Sherman said that he and others who backed the ballot measure respected the voters, but were “deeply disappointed” in the result.

“We will take some time to reflect on and process the outcome and find a path forward that works for the Royals and our fans,” he said.

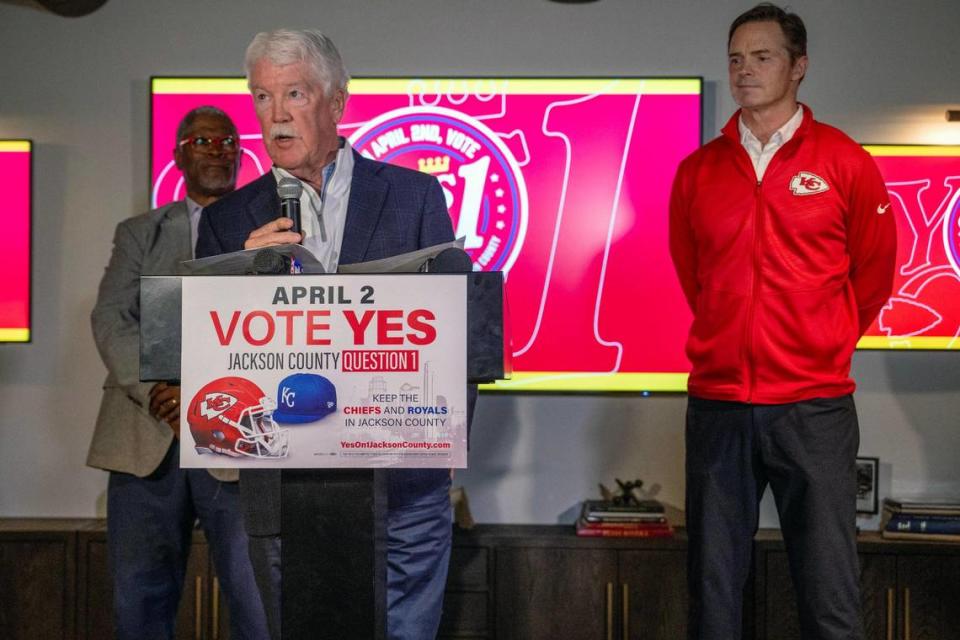

Question 1 supporter Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, agreed after the results cooled the mood at the “vote yes” election results watch party where Sherman gave his remarks.

“I hope that we will regroup and go back to the drawing board,” Kendrick said. “But who knows what this will ultimately lead to the two franchises determining what their next move might be. We obviously want them to stay in Jackson County.”

It’s hard to say what the election outcome means for the future of both teams. Prior to the vote, the Chiefs and Royals said they would explore all options, if the tax failed. The Chiefs have considered moving out of Jackson County when their lease of Arrowhead Stadium expires in January 2031, possibly to the Kansas side of the metro area.

The Royals’ options are less clear. Other metro areas without a Major League Baseball team would be interested in wooing the team with hefty incentives and a new stadium.

But Sherman said recently that he is wedded to the Kansas City area, where he has lived for nearly half a century, and that the implied threat that the Royals might leave town was a ploy suggested by the political strategists who ran The Committee to Keep the Chiefs and Royals in Jackson County.

“Somebody smarter than me finds that is a message that resonates,” Sherman told The Star’s Vahe Gregorian recently. “But I answer that question (will the Royals leave the Kansas City area) with, ‘This is my hometown.’”

All the same, Sherman and Clark Hunt, Chiefs chairman and CEO, struck an ominous tone in a joint letter addressed to fans and Jackson County voters that arrived in residents’ mailboxes on Monday.

“There is no redo of this campaign,” it concluded. “This is not going back on the ballot in November. There is no plan B.”

Despite the sentiment of the letter, it is technically possible for the teams to bring another tax to a future ballot. Opponents believe that would lead to a better deal for taxpayers and the community.

Among them was Jackson County Executive Frank White Jr., who had argued against putting Question 1 on the ballot before the Royals had even picked a site for their proposed stadium and before the county had negotiated new leases and community benefits agreements with both teams. The drafts of those documents were not made public until the final days of the campaign and are still unsigned, White noted Tuesday night at KC Tenants’ “vote no” watch party in the Crossroads.

“Those leases that they supposedly released at the end were one sided,” he said. “Nothing has been negotiated. And so the people deserve better. And so I’m just hoping that the teams will take a deep breath, and come back to the table. And we can sit down and work out a good deal that’s beneficial for the entire community.”

Expensive ballot campaign

Turnout was heavier than usual for an April election — with 34% in eastern Jackson County and 24% in Kansas City — owing to what was at stake and saturated media coverage that largely focused on the issues swirling around the Royals ballpark proposal, but still far lighter than a general election.

The Royals’ choice of the Crossroads site was controversial because it meant displacing dozens of businesses and taking those buildings off the tax rolls. Many fans of Kauffman Stadium were opposed to any move downtown.

Some voters said they favored a downtown ballpark but were uncomfortable with the lack of firm financial details in both proposals.

The tax failed despite a two-month media blitz in which the Royals and Chiefs spent heavily on TV, mailers and other forms of advertising, including social media, emails and text messages to get out the “yes” vote.

It was by no means the most ever spent in support of a local ballot issue in the Kansas City area. With inflation, the unsuccessful Bi-State II sales tax campaign to benefit the Chiefs, Royals and the arts community cost more in 2004: about $5.2 million in today’s dollars.

But the bills haven’t all been tallied for this election yet. At last count, the teams had contributed $3.2 million to their campaign, according to filings with the Missouri Ethics Commission.

That’s about 20 times more than their opponents, KC Tenants and the Committee Against New Royals Stadium Taxes, have said they planned to spend.

Implicit threat

Chiefs quarterback Patrick Mahomes and other local superstars urged voters to support the teams and keep the area’s upward momentum rolling. Organized labor and civic groups gave Question 1 a big thumbs up.

Kansas City Mayor Quinton Lucas gave his support as well, albeit in the final weekend of the campaign.

But underlying the positive messaging throughout was an implicit threat that failure at the polls could risk the loss of the teams after their current leases expire in January 2031.

In the immediate wake of Tuesday’s vote, the teams did not say what their plans would be.

Passage of Question 1 would have repealed the current 3/8th-cent capital improvements sales tax that voters approved in 2006 to pay for taxpayers’ shares of the costs of renovating Kauffman and Arrowhead stadiums. It would have been replaced with a new 3/8th-cent parks sales tax that would continue until 2064 and help pay for the Royals $1.3 billion proposed ballpark and the county’s share of the $800 million renovation of Arrowhead.

The teams argued that the measure would have meant no increase in taxes. But opponents noted that over those 40 years taxpayers would pay about $2 billion to cover debt payments and subsidize the teams, which would have shared in revenues over and above what was needed to cover those annual payments for the stadium projects.

Another criticism was that the county and the teams had not come to an agreement on their financial responsibilities for the projects. It was left up in the air as of Election Day.

Among the outstanding items in the proposed leases that were submitted for consideration last week were agreements between the teams and the county on how much county, state and city governments would contribute toward the total costs of the proposed construction projects.

The Chiefs had committed $300 million to their project, leaving $500 million to be covered by taxpayer funds from the county and other governmental bodies.

The Royals said they would put in an amount in that $300 million range, but were never specific.

Nor did the proposed leases spell out how much the county would be expected to contribute in up-front costs.

The citywide tenants union KC Tenants and other opponents of Question 1 cited those uncertainties as among the reasons they encouraged people to vote no. Some groups also felt that the tax dollars directed to the stadium projects would be better spent on things like affordable housing and improved public transportation.

Downtown baseball’s long saga

There’s been talk of building a downtown ballpark since before a Jackson County steering committee decided in May 1965 that building the current sports complex east of the General Motors Leeds assembly plant would be cheaper and less problematic than the second choice, which was to construct a domed, multipurpose stadium west of Municipal Auditorium.

The Leeds site was largely open land that might have become a park had the stadiums not been built the. Local officials felt it would have taken years to acquire all the downtown land that would have been needed and remove too many properties from the tax rolls.

“I think downtown has some advantages,” then-City Councilman Sal Capra said at the time, “but it would cost too much and take too much time.”

Seven years later, Arrowhead Stadium opened for the start of the 1972 football season, followed by what was then known as Royals Stadium that next spring.

Talk of building a downtown ballpark would not begin to get serious discussion until the early 2000s as part of the planning for a downtown revival that took shape with the construction a new arena, the KC Live entertainment district and scads of subsidized apartment buildings that were built where parking lots and slow-slung businesses had stood.

David Glass, who owned the Royals at the time, had previously been resistant to a move downtown. But with the Cardinals about to get a new, publicly subsidized downtown ballpark and the Royals and Chiefs seeing the need for renovations at the sports complex, Glass was suddenly open to the idea in a 2001 interview.

“Our approach all along has been that we wanted to improve Kauffman,” he said. “The most efficient use of money is to retrofit and renovate Kauffman and make it more competitive with some of the newer stadiums. But I’m surprised at the amount of interest there is in a downtown renovation project that would include a new stadium. There have been enough people who have said this might be the thing to do where you at least have to talk about it.”

Mayor Kay Barnes, who led the effort ford that downtown revival, agreed with Glass.

“A downtown stadium is definitely an idea that has bubbled up,” Barnes said. “I believe there is traction now that there hasn’t been in the past for this kind of facility. Now is the time to look at all our options.”

But the teams and the voters chose to renovate Kauffman and Arrowhead instead in 2006. It wasn’t until Sherman’s ownership group bought the Royals from the Glass family at the end of 2019 that momentum grew again for a downtown ballpark.

The Star’s Jonathan Shorman, Blair Kerkhoff, Kendrick Calfee and Natalie Wallington contributed.