With Missouri man in execution chamber, spiritual adviser tried to show ‘he was loved’

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Monday, 27 hours until execution

The sky darkened Monday afternoon as Matt Frierdich drove southeast from his home in Columbia to Bonne Terre to visit a man condemned to die the next day.

Minutes before on the way to the state prison, Frierdich had gotten word that Missouri Gov. Mike Parson would not grant Brian Dorsey, 52, clemency.

The moon drifted in front of the sun, a peculiar experience made all the more eerie as Frierdich processed the governor’s decision. It was not surprising — Parson has denied clemency to every death row prisoner facing execution since he took office in 2018.

But, “it was sort of like that last realization that here we are,” Frierdich said.

His journey to that moment began in early December when a friend who works in the federal public defender’s office asked if he would consider serving as Dorsey’s spiritual adviser.

About two years ago, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that spiritual advisers could pray with and touch prisoners in their last moments during executions.

Though he took some time to think over his friend’s request, the role fit his background. Frierdich, a 36-year-old native of Kirkwood, just outside of St. Louis, grew up in the United Church of Christ, which connects social justice to its ministry. He is now ordained in the denomination.

During seminary at Vanderbilt Divinity School, he worked with a Tennessee organization advocating for alternatives to the death penalty. He was also a hospital chaplain, including in a palliative care unit.

Frierdich moved back to the area with his wife and young child in July when he got a professorship at the University of Missouri.

On Dec. 13, days after Frierdich had agreed to support Dorsey, the Missouri Supreme Court handed down an execution date: April 9.

“Everything became a lot more urgent,” Frierdich said.

Frierdich and Dorsey emailed while bureaucratic steps to permit the adviser into Potosi Correctional Center got worked out.

They first met in February and again in March.

“We hit it off,” Frierdich said. The two had a connection and good conversations.

Frierdich learned that Dorsey had formed relationships with corrections staff and other prisoners “in a place that’s not made to create a community.”

Dorsey was the prison barber, where he was trusted with potential weapons, and cut hair for the warden, officers and other incarcerated people.

Parson rejected the pleas of more than 70 corrections staff members who supported commuting Dorsey’s sentence to life without parole and sparing him from the death penalty.

Monday, 24 hours until execution

Later Monday, Frierdich arrived at Eastern Reception, Diagnostic and Correctional Center, the prison that houses the state’s execution chamber where Dorsey had been transferred.

Frierdich said he wanted to know what was on Dorsey’s mind and found him in good spirits for the most part.

“These conversations go between laughing and crying,” Frierdich said.

The two met for just over an hour. They talked about TV shows and fond memories from Dorsey’s life. They confronted questions about what happens after death.

Dorsey wanted to know whether God would be harsh on him. Frierdich tried to impart “reassurance of love, unconditional love.”

Frierdich said Dorsey had complicated feelings about God, which he thought about in his final days. Dorsey considered himself a faithful person who was committed to his belief in God, but had a fraught relationship with church and religion.

Before Dorsey was sent to prison for killing his cousin Sarah Bonnie and her husband Ben Bonnie in 2006, he had tried several denominations, including Protestant and Catholic traditions.

But he never felt accepted.

“I think in general, the church, the way it manifests, isn’t always looking out for those people that don’t seem to fit in, and I think Brian felt that way,” Frierdich said.

In prison, Dorsey pondered questions about how the Bible was created and what it means to have a relationship with God and Jesus.

“He’s explored these things in a very thoughtful, rigorous way since he’s been in prison,” Frierdich said. “That emotional part still, it’s hard, you can’t think your way into that.”

Tuesday, nine hours before execution

As Friedrich prepared to meet with Dorsey for the last time before they would be together in the execution chamber, he worried if he’d “be able to live up to the moment and be comforting and caring in a moment that’s designed to be uncaring.”

He found strength in his faith and its tenets.

“The thing itself is grotesque but in that moment, to be able to do it with someone, that is what we do,” he said. “That is what the calling is, the faithful to be there in the hard spots.”

At the same time, the rest of life kept moving. Frierdich, who is teaching three courses this semester at Mizzou, had papers to grade and lectures to prepare.

“It’s a strange thing,” he said. “It feels like the world should stop if we’re going to do these kinds of things — and pause and reflect — but I don’t think that’s how it works.”

Being intimately close to the process, Frierdich said, has only solidified his feelings about the death penalty.

He came into the experience as “someone who finds the institution of capital punishment to be inconsistent with my faith background, with my political beliefs, with my understanding of what it means to do justice.”

“I feel confirmed.”

He also said it was not lost on him “that the center of the Christian faith is an execution.” That theological weight and symbolism, including how Jesus was betrayed and left behind, was “poignant when you’re advising someone on death row.”

Tuesday, seven hours before execution

Frierdich arrived at the prison around the same time Dorsey ate his last meal: two bacon double cheeseburgers, two orders of chicken strips, two large orders of fries, and a Casey’s pizza with sausage, pepperoni, onion, mushrooms and extra cheese.

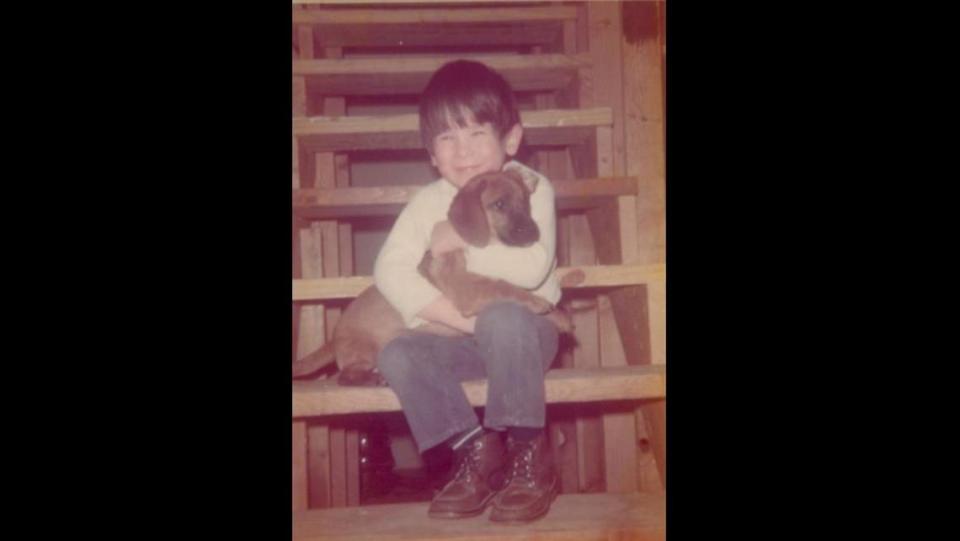

They talked about music. Dorsey was a fan of everything from Shania Twain to the Beastie Boys and Pink. Dorsey also shared photos he had on his tablet. One photo showed Dorsey as a young boy with his grandfather. Another captured him laughing with his cousins at a birthday party.

“You think about the life trajectory and you know, imagining at that time you had no idea where his life would go,” Frierdich said.

They also sat in prayer.

“In some ways, he had this demeanor of like, ‘I’m just ready,’” Frierdich said. “I don’t want this to linger any longer, I’m not afraid of dying, I just hate waiting.”

6 p.m. Tuesday

When Frierdich entered the execution chamber, Dorsey had already been hooked up to the IV that would deliver the fatal dose of pentobarbital. A white sheet had been placed over him, up to his shoulders.

Frierdich was allowed to touch Dorsey’s left-hand shoulder.

Dorsey, who was wearing eyeglasses, smiled when he saw his legal team in a witness room to his left. They were wearing matching maroon T-shirts emblazoned with a white heart.

At one point, he asked Frierdich what time it was and when it would start.

As a hospital chaplain, Frierdich had learned that the moment of death is humbling, terrifying and sad. But there’s also a “weird peace” that emerges “out of being at the depths of that sadness.”

Dorsey had found that peace even before dying.

Dorsey “was able to articulate, ‘I’ve said what I needed to say, I’ve expressed sorrow and guilt, I’ve asked for forgiveness. I’ve done all the things — I’m ready,” Frierdich said.

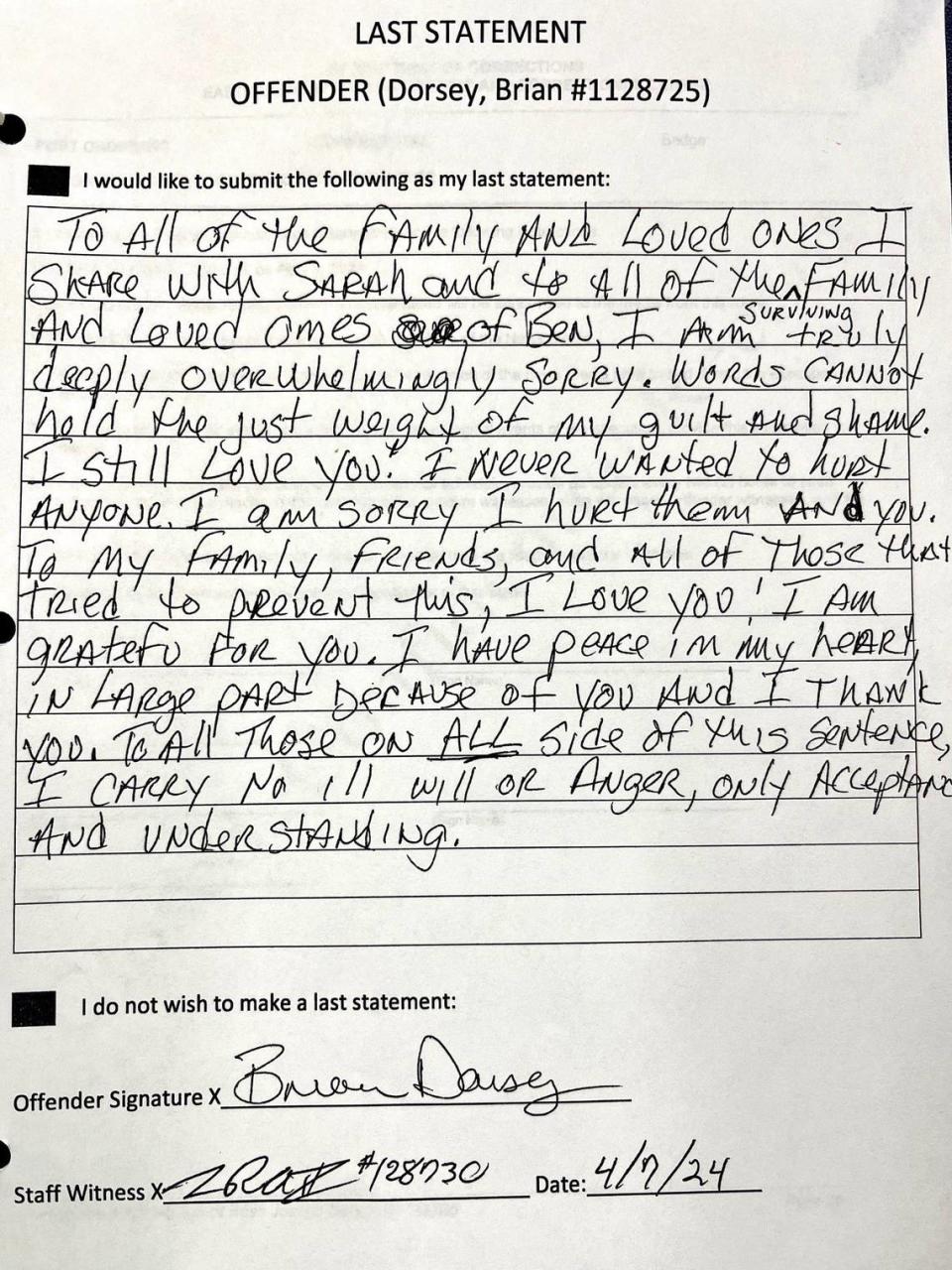

In his final statement, Dorsey wrote that he was “truly deeply overwhelmingly sorry.”

“To my family, friends and all of those that tried to prevent this, I love you! I am grateful for you. I have peace in my heart in large part because of you.”

Frierdich said Dorsey appeared lucid and comfortable.

He spoke to Dorsey.

“I was just trying to convey that he was loved. He was loved by the (legal) team. You know, that he was deserving of God’s love and that it was a gift freely given. And that we are not defined in God’s eyes by the worst things we’ve done.”

As the drug coursed through Dorsey’s veins, his chest rose and fell heavily a couple times. Then he took a few shallow breaths. Then he was still.

“This is the thing I told him over and over as he died, is that ‘We love you Brian and God loves you’ and hopefully that’s the last thing he heard,” Frierdich said.

Dorsey was pronounced dead at 6:11 p.m.

The highway was dark and quiet as Frierdich drove back to Columbia later Tuesday.

When he stopped for gas at a Casey’s, he was reminded of the pizza in Dorsey’s last meal, which had come from the convenience store.

Frierdich called his family, who said they were proud of him.

Wednesday, 20 hours after execution

Friedrich said he was feeling how he expected: disjointed and weird.

While going through the whole whirlwind process he thought, “I’ll pick up the pieces later.”

Now, as he resumes normalcy, he has begun reaching out to people to express his appreciation for them and to start figuring out how to talk about his experience and make sense of it.

Meanwhile, he also is focused on teaching his classes and his family.

Frierdich said he has felt waves of gratitude for being part of Dorsey’s journey and coming to understand the importance of a role like spiritual adviser when someone is facing death by execution. But he has also felt “heartbroken by the bleakness of where we are with how we respond to injustices in society.”

“So it’s a waxing and waning.”