Southern labor union victories: Will momentum persist or stumble?

As he stood before jubilant Volkswagen workers after they overwhelmingly welcomed the United Auto Workers into the Chattanooga plant on April 19, the union's hard-charging new president Shawn Fain hailed the victory as a rebuke to everyone who said labor could not win in the South.

On Monday after the results were certified, the UAW and VW said in a statement they were "jointly committed to a strong and successful future" for the plant in Chattanooga.

Many have called the UAW's win in Chattanooga historic, a strong signal that workers in the South are now open to unionizing as U.S. automakers expand into the region.

But experts who study the American labor movement cautioned that one win at one plant, even with a large margin of victory, is not enough evidence to say labor's fortunes have changed in the South, a region that has long resisted organized labor.

"I think it's important," said David Anderson, a Louisiana Tech University history professor who studies labor unions. "I don't think we have the perspective to call it historic."

In mid-May, another referendum on unions in the South is lined up.

Workers at the Mercedes-Benz plant near Tuscaloosa, Alabama, will have their chance to vote on whether they want to join the UAW. The outcome of that election will be an important test: Has the South changed its attitude on labor? What forces have led to that shift? Is it a misconception that Southerners are inherently hostile to organized labor?

Do the numbers tell the whole story?

Most Americans say they support unions — 67% of people reported a favorable view of unions in a Gallup poll last year.

Despite this sentiment, union membership has fallen over the years. Only 10% of U.S. workers belong to a union, according to the latest data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. South Carolina has the lowest unionization rate in the country, at 2.3% of workers.

Unions, however, do have a presence and a history in the South.

Rusty Adair, a professor at Auburn University's business school, had a long career in management with International Paper. He noted that all three of the company's paper mills in Alabama are organized and that unions are common across the South in the paper industry.

"The automakers are getting the headlines right now because they're going somewhere new," Adair said.

Alabama Power has unionized workers, Adair said, and the state's teachers' union is strong.

Alabama does have the second-highest percentage of unionized workers in the South, after Kentucky. But its 7.5% rate of unionized workers is below the national average.

Unions in the South harken back to the 1800s when Southern politicians and business leaders lured Northern companies with relatively low rates of organized labor.

But Anderson points out that many sectors in the South, like steel and mining, were unionized throughout the 20th century at almost the same rate as in Northern states.

The relatively low rate of unionization has more to do with the South's agriculture-based economy, Anderson said, adding that the largest historic manufacturing sector in the South was textiles — an industry where unions never had much success.

Coronavirus pandemic upheaval reignited union support

Last year, the UAW went on strike against the three largest U.S. automakers: Ford, General Motors and Stellantis, the international conglomerate that includes Chrysler. The union won a favorable contract for the 145,000 workers at those companies, including the unionized employees at the GM plant in Spring Hill outside Nashville.

Workers at VW in Chattanooga said that strong contracts for Ford, GM and Stellantis workers motivated them to push again for a union after narrow defeats there for the UAW in 2014 and 2019.

The gradual resurgence of labor across the United States, however, can be traced to the upheavals of the COVID-19 pandemic, said sociologist and labor expert Daniel Cornfield of Vanderbilt University.

"The big concerns grow out of a long-term trend in the United States toward a widening income gap that has been unrelenting since 1968 or so," Cornfield said. "The pandemic may have accentuated some of the frustrations for workers in the lower income tier of this economy."

The recent efforts to organize Starbucks workers across the country are part of this trend, Cornfield said.

Workers have also seen their jobs become precarious as more companies rely on temporary workers, Cornfield said. The use of temporary workers, who often worked in positions for years with fewer benefits than permanent workers, was a major issue in last year's UAW strike.

Right-to-work laws challenge unions in the South

In the days leading up to the vote in Chattanooga, a coalition of six Southern governors, including Bill Lee of Tennessee and Kay Ivey of Alabama, issued a statement urging workers to reject the UAW. The governors' arguments failed to sway the VW workers in Tennessee. But the Republican lawmakers have successfully pushed back against unions in the past.

Across the South, right-to-work laws, which allow workers represented by unions to not pay dues, hamper the ability of unions to operate. Automakers also benefit from lucrative state incentives. After pressure from Tennessee lawmakers in 2019, VW toughened its stance against the UAW in that election the union narrowly lost.

Who sits in the White House, experts said, can matter more in union drives than what local politicians want. The president appoints the five-member board and the general counsel of the National Labor Relations Board, which has a huge influence on how union campaigns are conducted.

Democrats have historically been pro-union but not every president has fallen in line. President Barack Obama made few changes at NLRB in favor of unions.

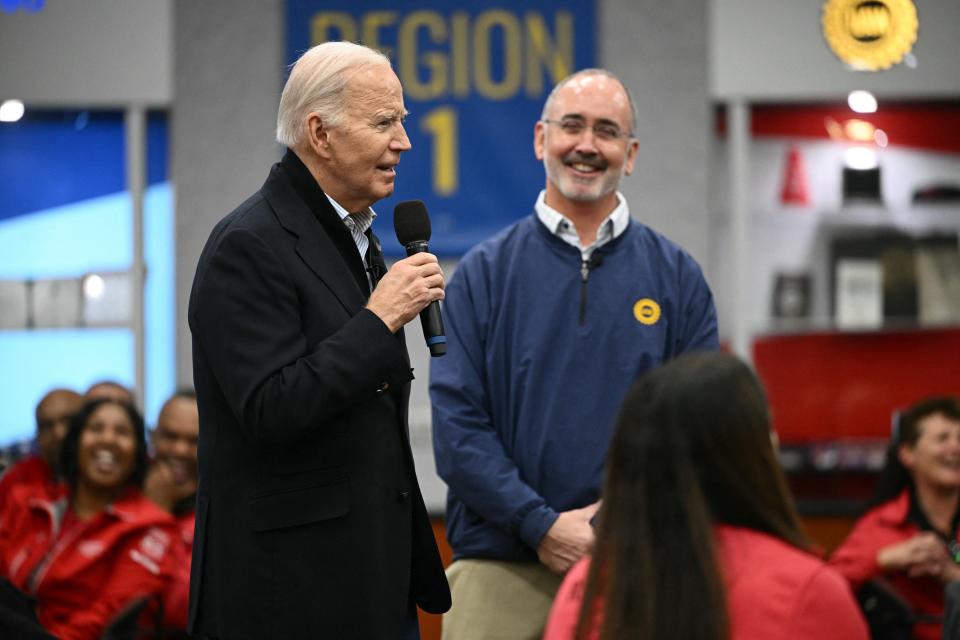

President Joe Biden, however, has pushed hard to tilt the NLRB in favor of unions.

"This is probably the most pro-labor president I have seen in my lifetime," said Scott Baier, chair of the economics department at Clemson University. "For the last 30 to 40 years, I don't think we've had an executive branch that has been more pro-labor than this one."

Republicans will have a chance to reshape the NLRB if they retake the White House.

"If the White House flips, then I think it basically puts a significant stall on these types of movements," said Adair of Auburn.

What will the future bring?

Some experts say another strong win for the UAW at the Mercedes plant in Alabama would convince them labor's fortunes in the South have changed. Others are waiting to see if the UAW can win over workers in Smyrna at the Nissan North America plant, the first foreign-owned automaker in the South. Workers there in the past have repeatedly and resoundingly rejected joining a union.

Still other experts say the real test for the UAW in the South will be whether it can unionize the many parts' manufacturers across the region that supply the automakers.

"Organizing the parts sector in the South would be important, because those (businesses) are the supply chain," Anderson said. "If anything, COVID taught us the importance of supply chains and what we call essential workers."

Recent years have also shown how events can upend expectations.

"There's a fair amount of momentum now for unions," Baier said. "But with a lot of things over the last five to six years, I've looked and thought: 'I don't know what's going to stop that.'

"And then you have one event that seems to turn the whole tide rather quickly."

Todd A. Price is a regional reporter in the South for the USA TODAY Network. He can be reached at taprice@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: UAW victory, Mercedes-Benz vote may paint picture on labor in South