Six Des Moines Register, WHO and other Iowa journalists who reported on World War II

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Six reporters with Iowa roots were among the many journalists who branched out across oceans and through combat during World War II to cover some of the most pivotal events in U.S. and human history, often alongside American troops.

These six Iowans also were spouses and parents, and not everyone made it home alive.

Here's a look at who they were and what they did during the war.

Gordon Gammack, George Bede Irvin and the personal costs of war reporting

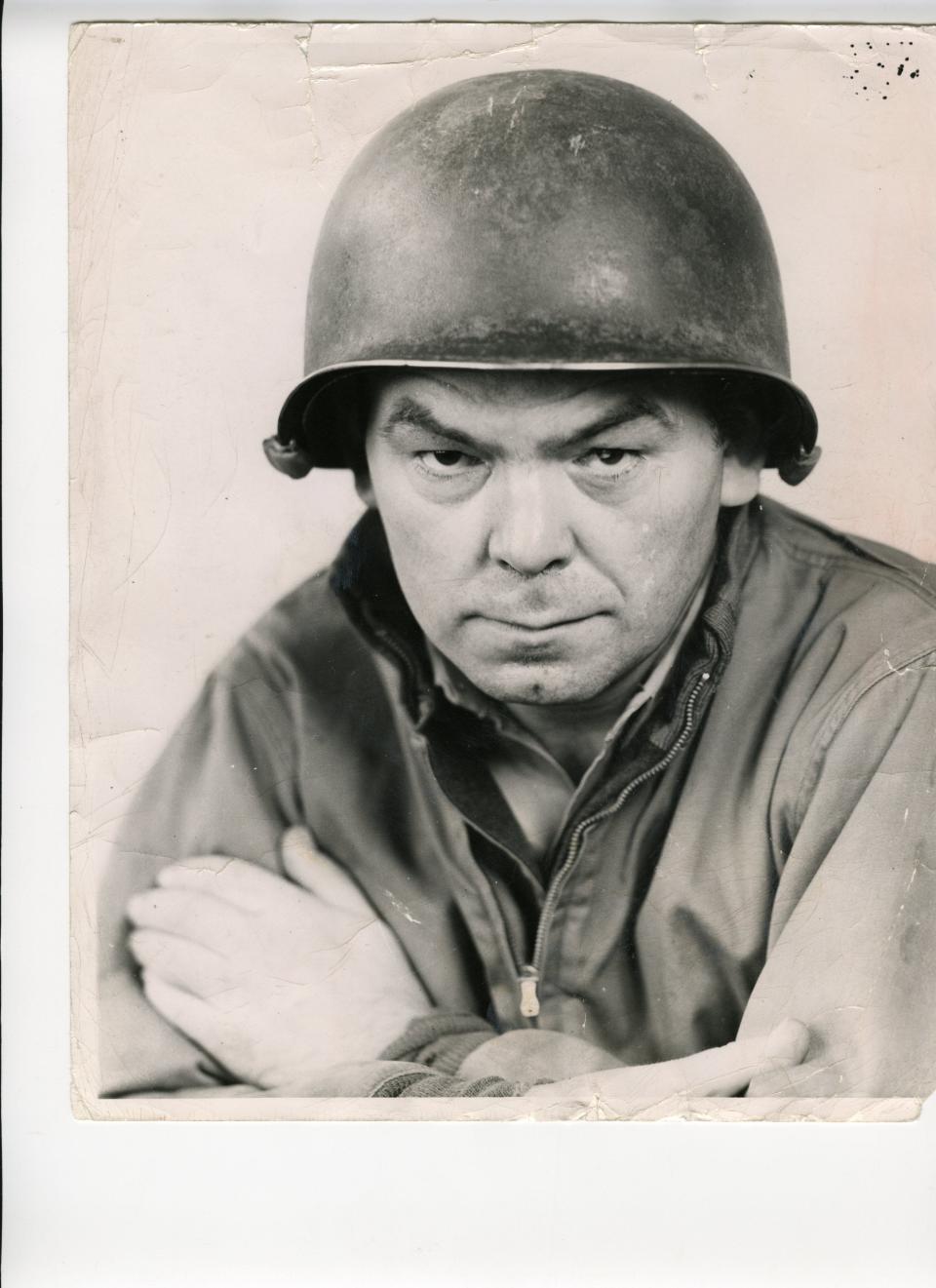

Gordon Gammack was a columnist for the Des Moines Register and the Des Moines Tribune — a separate newspaper owned by the same family who owned the Register.

Before he became a war correspondent, Gammack also reported on crime, sports, the Iowa House of Representatives and even Hollywood moviemaking. He also was a radio reporter for what later became KCCI-TV.

Kaye Gammack, his wife, later told the Register's Chuck Offenburger she never expected her husband to go off to war — he was deferred from the draft because he was blind in one eye from a car accident when he was in college and he had a 2-year-old daughter and infant son at home.

"He loved it, you know?" she told Offenburger of her husband's relationship with war reporting. "He always wanted to be where the big story was. And he had such a way of wangling his way into places. If the Army brass said there was no way he could do something, that became a challenge for him to get it done," she added.

Gordon Gammack came home after following the 34th U.S. Division in its fight against Nazi Germany through North Africa and Italy, crossing into France two weeks after the D-Day invasion. He also covered the war in the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany. He got a ride on the first American vehicle to enter Paris after its liberation from the Nazis.

But a fellow correspondent and friend who had worked with Gammack did not make it home alive.

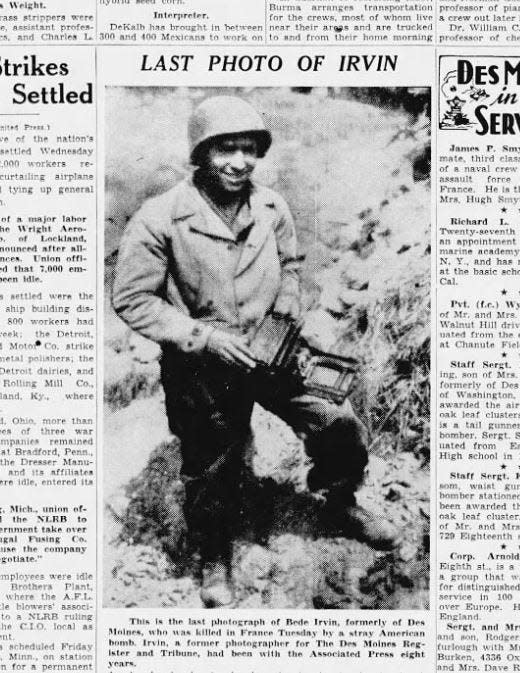

George Bede Irvin was a Des Moines native who played football in high school, attended the University of Iowa and Drake University and was a photographer for the Register and Tribune. His first wife was the Register's society editor, but after a divorce, he later met Kathryne Hankin in 1935 while on an assignment in Newton.

She later told the Detroit Free Press' Neil Shine that Irvin asked her to marry him on their first date.

"I said yes. I had never even kissed him, but it seemed like the most normal, natural thing in the world for me to tell him I would marry him," she said.

She was 23 and he was 25 when they married in Newton in January 1936.

Irvin went on to be a photographer for the Detroit bureau of the Associated Press, and it was from there that he volunteered to cover the war as a correspondent in April 1943.

He and his wife wrote and sent letters to each other almost every day.

A columnist for the Mount Clemens, Michigan, Monitor-Leader later described Irvin as "cordial and helpful" and a photographer who "always wanted to be where the pictures were best."

Irvin took from a plane one of the first pictures of the beachhead in the D-Day invasion on June 6, 1944, and then arrived on the ground in France two days later.

Irvin was killed on July 25, 1944, two days shy of his 34th birthday, by an American bomb that fell short of its target near St. Lo, France. Irvin was said to have been sitting in a Jeep when he hesitated and picked up his camera before he dove for cover in a ditch. A bomb fragment hit him mid-dive and instantly killed him.

The Detroit Free Press later reported that Kathryne Irvin wrote after her husband's death to his closest friend, a fellow AP photographer in the war: "I find myself putting away little chitchat in my mind for future letters I will be writing Bede — and I remember there can be no more letters to write to him, can be no more mail coming from him … Nothing we ever dreamed of together can ever come true now. Little sounds of shattering hopes and dreams are big noises now — nothing to hope for — and no understanding."

Irvin was posthumously awarded a Purple Heart as a civilian and was one of 67 journalists to be killed covering World War II, according to the Freedom Forum’s Journalists Memorial.

Gammack and about 20 other correspondents attended Irvin's burial in France on what would have been Irvin's birthday. His grave is in the Normandy American Cemetery.

More: One of Iowa's Rosie the Riveters, who worked on World War II bombers, dies at 99 years old

Gammack wrote a story for the Register on the service and in it noted that Irvin was the first civilian correspondent with American forces to die in France during the war.

Maj. Gen. Lewis H. Brereton, commander of the U.S. Ninth Air Force — which included the plane that dropped the bomb that killed Irvin — said in a statement to the Associated Press that he had personally gotten to know Irvin and he exemplified correspondents' role in the war.

"He was an unarmed observer who, heedless of personal danger, flew with us, lived with us and worked with us that through the medium of his profession he might bring home to all of us the truths of war," Brereton said.

William Shirer, who snuck uncensored truth out of Nazi Germany

Iowa connection — Grew up in Cedar Rapids and graduated from Coe College.

Notable work and experiences in the war — "Berlin Diary: The Journal of a Foreign Correspondent, 1939-1941" was listed in 1999 by New York University as No. 21 on the list of the top 100 works of journalism in the 20th century.

As a CBS correspondent in Berlin in 1939 and 1940, William Shirer's radio reporting was censored by the Nazis, though he did use vocal inflections and American slang to try to get around the censorship. But Shirer also had written secret diaries in Berlin since 1934 and he snuck them out in December 1940.

The Register serialized "Berlin Diary." Shirer, speaking in November 1941 to a sold-out auditorium in Des Moines, told the audience he wanted the U.S. to aid England and the Soviet Union against Germany "because I want to save the United States … Hitler has to be beaten."

More: World War II's Ghost Army, including an Iowan, to receive the Congressional Gold Medal

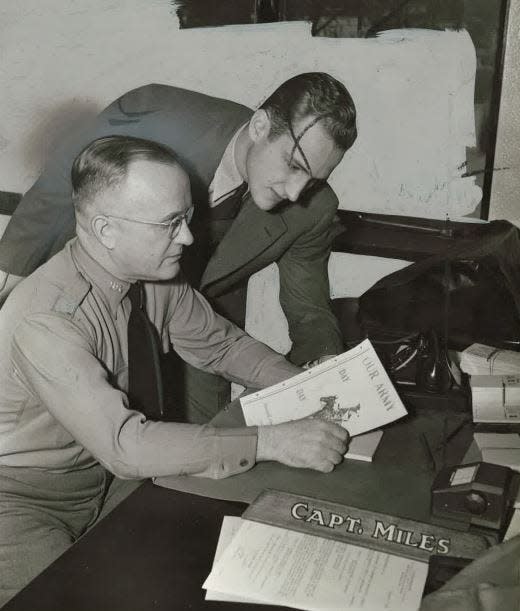

Frank Miles, whose reporting allowed him to visit his son's grave

Iowa connection — Drake University Law School graduate; Des Moines city treasurer for two years; Navy veteran of World War I who was a founder and the longtime editor of the Iowa Legionnaire veterans' publication; 1946 Democratic candidate for Iowa governor.

Notable work and experiences in the war — Frank Miles was an Army major assigned to the Iowa selective service system during the war but left to be a war correspondent for the National American Legion publication, Iowa Daily Press Association and WHO radio. He reported from Italy, France, Germany and the Pacific.

One of Miles' sons, 21-year-old Army 2nd Lt. William Miles, was a pilot of an American bomber who was killed by anti-aircraft fire over Italy in May 1944 before he got the chance to read the letter his father wrote to tell him he'd be coming to Europe as a correspondent.

Miles got to visit his son's grave in Italy in August 1944. He wrote in a story for the Iowa Daily Press Association: "I knelt down and talked through the Lord to him and his comrades sleeping there and elsewhere, then arose and saluted him and all of them and departed with pride and contentment in my broken heart."

More: A Iowan who fought in World War II was identified 80 years after his plane crashed

Herb Plambeck, who stood amid the Nazis' ruins and atrocities

Iowa connection — Grew up on a family farm in Scott County and became a longtime radio reporter for WHO covering Iowa farms as the first full-time farm broadcaster in the U.S.

Notable work and experiences in the war — Herb Plambeck entered Dachau concentration camp in Germany the day after American troops reached it in 1945. On Victory in Europe Day — May 8, 1945, — he climbed up with four other correspondents into Hitler's former mountaintop retreat, known as Eagle's Nest, carved his name and press affiliation above a fireplace and took out some teacups, saucers and stationery as souvenirs.

Plambeck told the Register's Chuck Offenburger 50 years later what he saw at Dachau still haunted him. "Bodies were stacked 10 feet high in the yards outside the camp," he said.

"It will probably be my last memory … I make it damned clear whenever I write or talk that, yes, (the Holocaust) happened."

He later told World War II veterans gathered outside the Iowa State Capitol that if not for them, "madmen like Hitler, (Benito) Mussolini, (Hideki) Tojo and others like them would have prevailed, and I can't imagine the specter of the world we would have now if they had."

Recordings of some of Plambeck's WHO broadcasts from the war are available at whoradioiowa.omeka.net/items.

More: Humanity 'experienced tremendous loss' with death of Des Moines' last Holocaust survivor

Jack Shelley, who was on the ship where the end of the war was decided

Iowa connection — Born in Boone; longtime WHO radio reporter and later the station's news director for radio and TV; longtime journalism professor at Iowa State University

Notable work and experiences in the war — Jack Shelley covered the notorious German counterattack known as the Battle of the Bulge. He recorded the first interviews with the American bomber crews who had dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945. And he was on the deck of the USS Missouri in September 1945 reporting on the formal Japanese surrender.

Shelley later described to the Register that the surrender of Imperial Japan on the USS Missouri as the most emotional moment of the war for him.

After Gen. Douglas MacArthur signed some documents in the ceremony, Shelley said MacArthur handed a pen to Gen. Jonathan Wainwright, who had been a prisoner of war held by Japanese forces and starved and mistreated in captivity. Wainwright looked "gaunt and thin," with his clothes loosely hanging on him.

"General MacArthur called him forward and handed him this trivial-looking little fountain pen. Such a trivial instrument for such a momentous document. I still get emotional after all these years," Shelley said.

Recordings of some of Shelley's WHO broadcasts from the war are available at whoradioiowa.omeka.net/items.

More: Remembering Iowa's five Sullivan brothers, who died together in 1942 aboard the USS Juneau

Phillip Sitter covers the western suburbs for the Des Moines Register. Phillip can be reached via email at psitter@gannett.com or on X, formerly known as Twitter, at @pslifeisabeauty.

This article originally appeared on Des Moines Register: Here are the Iowa journalists who covered World War II overseas