Rubin: Love and lessons endure in old photo of Hamtramck star and Black baseball immortal

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Two Saturdays after Steve Gromek died in 2002, his middle son's phone rang at 7 a.m. The caller was a judge he knew who said he'd had to restrain himself from calling at 6.

"Go out and buy every New York Times you can find," the judge told attorney Gregory Gromek, still prying his eyes open in Beverly Hills. His dad was on page 18, above the fold, in a quarter-page obituary with maybe the most perfect headline ever written:

"Steve Gromek, 82, a Pitcher Who Is Best Known for a Picture."

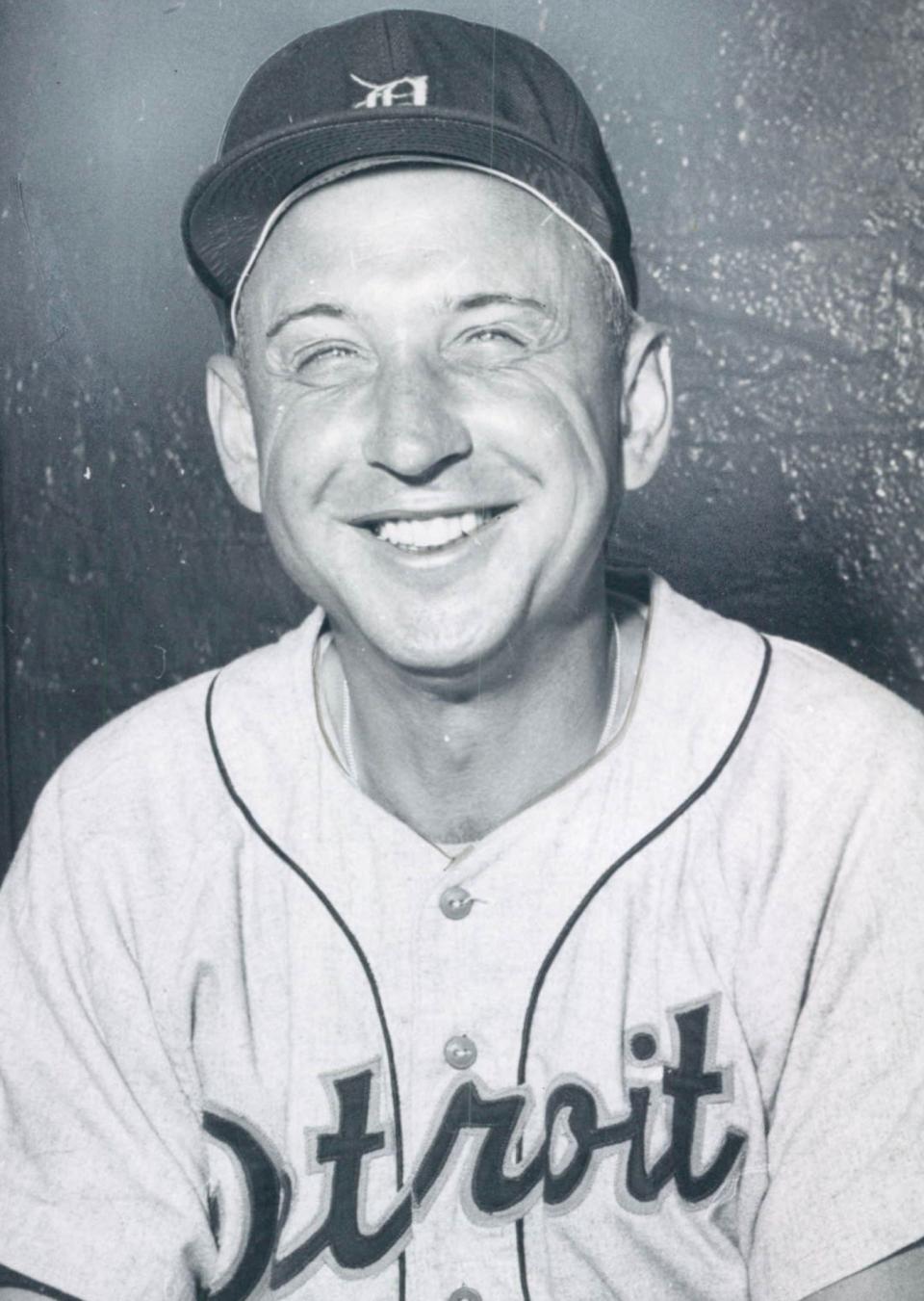

Steve Gromek, the pride of Hamtramck until he was shunned there, pitched in the American League for 17 seasons, most of them with the Cleveland Indians and the last 4½ with the Detroit Tigers. In 1948, as an Indian, he beat the Boston Braves 2-1 in the fourth game of the World Series, and the teammate whose 425-foot home run provided the margin of victory embraced him in front of Gromek's locker.

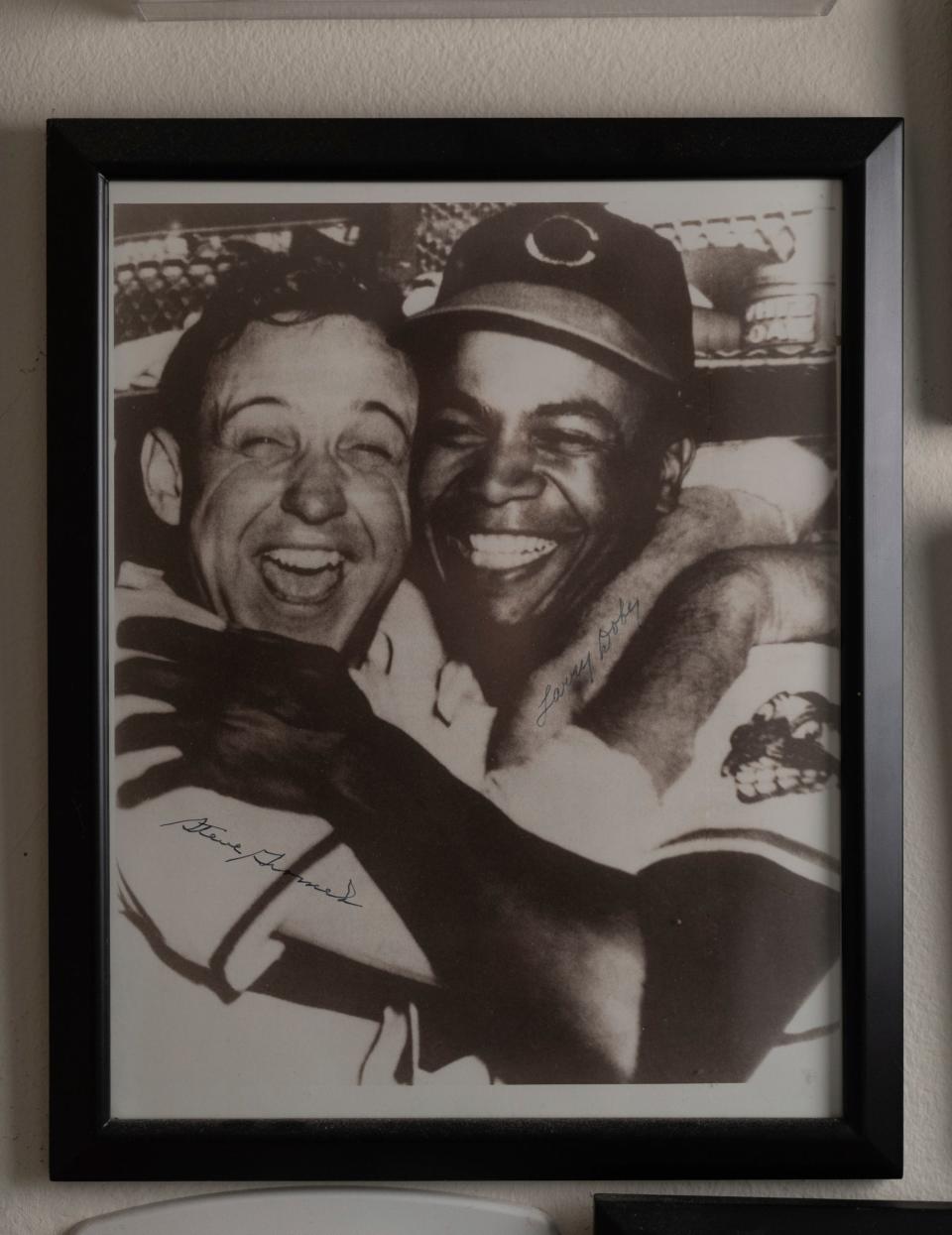

The teammate, Larry Doby, was Black ― only the second of his race in the majors leagues when he joined Cleveland the year before, 81 days after Jackie Robinson integrated modern baseball. In the photo by the Cleveland Plain Dealer of that jubilant hug, they are cheek to cheek, smile to smile, victor to victor.

Elsewhere, some people saw more. The photo had repercussions that surprised Gromek by their venom and Doby by their endurance. Copies were hung with pride on the walls of both players for decades, and hang in their children's houses today.

A few months ago, the image was preserved in a Congressional Gold Medal, an exception to a long-standing custom that Larry Doby Jr. informed the U.S. Mint was a deal breaker. No reproduction of the photo on the back of his late father's tribute, with a second person alongside the honoree? No shared glory for Steve Gromek? No thanks.

Now Gregory Gromek has a bronze replica of the medal on a display table beneath the black-and-white photo on his wall. Since the ceremony in the National Statuary Hall at the Capitol on Dec. 13, what would have been Doby's 100th birthday, CBS and the MLB Network have revisited the story.

Gromek hopes that every viewer sees what he does in the photo, and what he always has:

"Pure joy."

The path to the picture

The Indians are the Guardians now, and the unsightly caricature known as Chief Wahoo on the left sleeve of their 1948 uniforms has been retired. Major league baseball has nearly doubled in size, from 16 teams to 30, and the population of players is not quite 60% white, with the next largest block Hispanic or Latino at 30.2% and then Black or African American at 6.3%.

Joy remains joy.

His low-key dad rarely beamed the way he did in the photo, Gregory said. He didn't talk about his career unless he was asked, and his sons agree they should have had more questions. But the picture was always on display, next to some random plaques and honors and a few golf trophies.

Gregory, 74, and his brother Carl, 76, of Lake Orion, both played baseball at Florida State, made their way home to Michigan and became successful lawyers. Gregory had spent four years as a minor league infielder and pitcher in the Tigers' organization, then decided he could make a better living in the real world.

Their dad never pushed them, he said. Grandpa taught Gregory's 6-year-old son how to execute a fadeaway slide on the living room carpet, but when the boy decided to quit baseball in high school, it was the former big leaguer who advised, "He should do what he wants to do."

What Steve Gromek always wanted to do was play, but St. Ladislaus High School couldn't afford a team or a coach. Signed from a summer league as an infielder, he moved to the mound at 20, made his debut with Cleveland at 21 in 1941, and was in the majors to stay by 24.

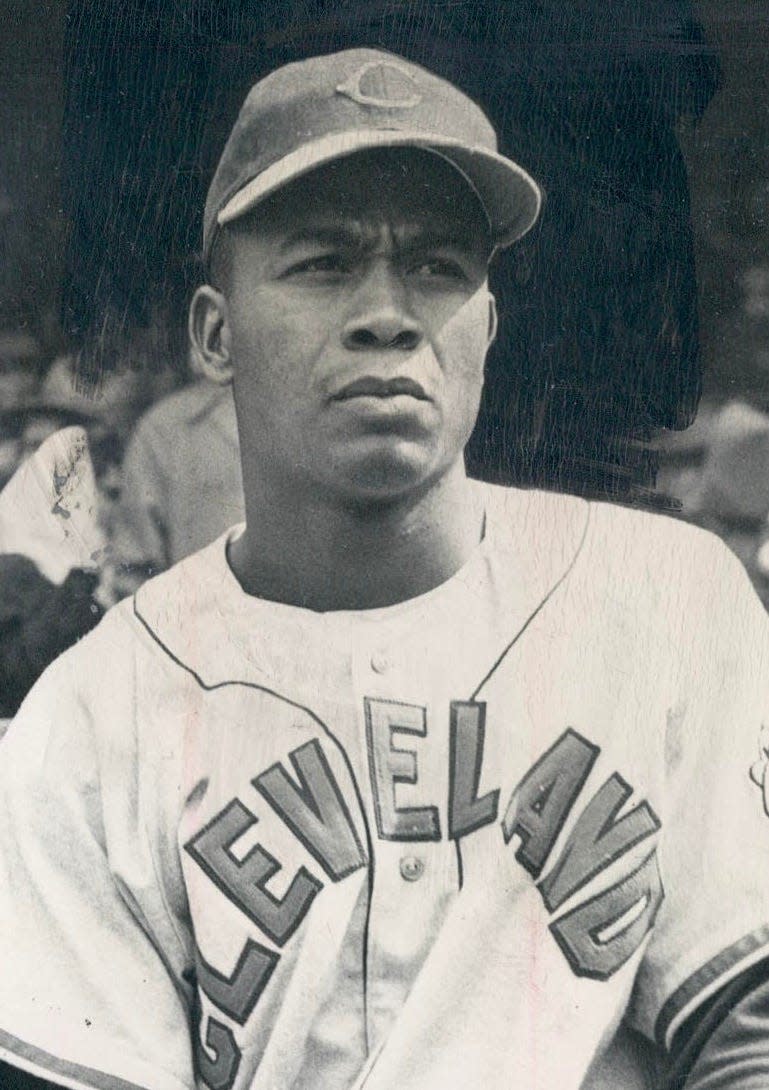

Doby was also entrenched by 24, but his path included more than two years in the Navy during World War II, and choppy seas once he joined the Indians.

An unwelcomed arrival

Robinson's debut with the Dodgers followed a well-publicized season in the minors. Doby's contract was purchased out of the Negro National League in July 1947, and his insertion onto the Indians' roster during a road trip to Chicago was a lightning bolt.

As he introduced himself on his first day, multiple teammates barely made eye contact and at least four refused to shake his hand. Two turned their back.

"It's a good thing for me," said Doby Jr. in the MLB Network report, that his father never revealed their names.

Doby took the field to warm up, and stood ignored for what he remembered as five full minutes as his teammates played catch. Finally, second baseman Joe Gordon ― like Doby a member of the Baseball Hall of Fame — gave him a proper ballplayer welcome, a greeting that sparked a friendship.

"Hey, rookie," Gordon said, "you gonna just stand there, or do you want to throw a little?"

Doby played sporadically that season. The next, 1948, he became a valued contributor as an outfielder, batting .301 in 121 games. Yet he often had to stay in boardinghouses or Black-owned lodgings on the road, or be sneaked into the team hotel by an Indians executive.

This was seven years before Rosa Parks boarded the Cleveland Avenue bus in Montgomery, Alabama, and declined to give up her seat. This was 16 years before President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

This was a time when a picture of Gromek and Doby hugging was a revelation, or even a revolution.

Chilly reception at home

The Indians beat the Braves in six games. Gromek came home for the winter to more than the usual frost.

There were hostile letters in his mailbox. People he considered friends wouldn't speak to him.

In a Hamtramck bar, he told the Society for American Baseball Research, he said hello to a former amateur teammate, "and he ignored me."

"Oh, Christ," the bartender told the World Series hero, "it's that picture you took with Larry Doby."

The former teammate thawed enough to grouse that "you could have just shook his hand." But a truer friend that day, Gromek said, took a different stance: "If I was in Steve’s shoes and Doby did what he did, I would have kissed him.’ ”

In the Pittsburgh Courier, a leading Black newspaper, columnist Marjorie McKenzie Lawson saw more than an embrace.

Lawson earned two degrees from the University of Michigan, then became a lawyer, the civil rights director for John F. Kennedy's presidential campaign, and a judge.

"That picture of Gromek and Doby has unmistakable flesh and blood cheeks pressed close together," she wrote as the cheers were still ringing, "brawny arms tightly clasped, equally wide grins. The chief message of the Doby-Gromek picture is acceptance."

No envy, but few frills

Gregory Gromek said his dad didn't talk about the hostility any more than he spoke of the triumphs.

Everyone has peak moments, he'd say. His just happened to have large audiences.

When the cheering stopped, he took a job selling insurance for AAA. He and wife, Jeanette, whom he'd met while working an off-season job when most athletes needed to do that, raised their two ballplayers in Beverly Hills, lost a third to a cerebral hemorrhage during a high school practice, and cut corners where they could.

Carl had been accepted to Notre Dame, for instance, but even at 1960s rates, the price seemed unworkable. When Florida State offered a baseball scholarship, the family drove nonstop to Tallahassee to consider the campus, saving the cost of hotels.

"My dad was always so happy for modern guys making a lot of money," Gregory Gromek said. There was no jealousy; what he didn't earn in salary, he made in memories.

He had friends from the game, and home movies of his kids in a hotel pool at spring training, riding on the shoulders of Al Kaline. He had shirts no one else could wear, an unavoidable expense, custom made with the right sleeve 2 inches longer than the left after two decades of throwing rising fastballs.

More: Rubin: Metro Detroit witness in trial tied to shooting by Alec Baldwin is pleased with role

He had the photo, and a bond.

Memories and milestones

Doby played for the Tigers in the waning days of his career, 18 games at age 35 in 1959.

Detroit offloaded him to the Chicago White Sox, and he retired at the end of the season. Most of the rest of his working life was spent in sports: scout, coach, a bit more than half a season with the White Sox as baseball's second Black manager, a decade in the front office of basketball's New Jersey Nets.

Like Steve Gromek, he rarely spoke to his kids about his baseball career, in part because some of the memories hurt. He had two stock responses to questions, Doby Jr. told The Athletic ― "Go look it up in the history books," and "That was yesterday. I deal with today."

Yesterday meant hearing the same slurs Robinson did, but in different cities, surrounded by fans and opponents vomiting hatred and ignorance on the first Black player they'd had a chance to boo.

The echoes stayed with him until he died of cancer at 79 in 2003, about 15 months after Gromek died of pneumonia and complications of a stroke at 82.

Of the two, Doby had the more storied career. Gromek won a solid 123 games, including 19 in one season for the Indians and 18 in 1954 for the Tigers. Doby was an eight-time All-Star who led the league in home runs twice.

Gregory Gromek was on hand when a CBS reporter asked Doby Jr. about the highlight of his dad's tenure in the game. Was it winning the World Series? One of his 273 home runs? Being selected as a Hall of Famer?

"No," Doby Jr. said. "It was the picture."

Lesson in black and white

A baseball and basketball player at Duke, raised in his father's home state of New Jersey, Doby Jr. has spent a quarter-century as a member of Billy Joel's road crew.

He is used to high climbs and tight spaces, and he was not one to get dizzy when he was approached in 2018 about the Congressional Gold Medal for his dad.

The medal is the United States' oldest civilian award, dating to 1776, and, along with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, it's the most prestigious. The lengthy selection process starts with two-thirds approval of both the Senate and House of Representatives, who must agree that an individual or institution made a long-term impact on America's history and culture.

The front of Doby's medal depicts him with a bat across his shoulder. The U.S. Mint resisted when Doby Jr. pushed for the back side to reproduce the pose in the photo, so he pushed again. OK, came the answer, and then he had to get permission from the Gromeks.

Carl laughed as he recalled the conversation to the MLB Network. "Are you kidding? What an honor!"

Carl drove 12 hours to the ceremony because his mother, 99, couldn't fly. The Gromeks arrived in bulk, with four generations, for what proved to be Jeanette's last trip; she died Feb. 21.

Doby Jr. had an admonition for the members of Congress in attendance as he gave his speech of thanks.

"There's an aisle between you," he said, "not a barrier."

If they need a reminder down the road, he can show them a picture.

One of the few heroes to endure into adulthood for Neal Rubin is Bill Veeck, the Cleveland Indians owner who brought Larry Doby to the major leagues. Reach Neal at NARubin@freepress.com.

In keeping with a ballpark theme, click here to subscribe to the Free Press for mere peanuts.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Photo of MLB players Steve Gromek hugging Larry Doby drew hostility