Ross Douthat at Utah State: Beyond ‘the fear that holds the conservative coalition together’

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“We’re going to talk about religion, politics, and the media — in other words, all the things you really don’t want to talk about with your uncle at Thanksgiving,” said Patrick Mason, professor of religious studies and history at Utah State University, as he began a conversation with New York Times columnist Ross Douthat on Thursday.

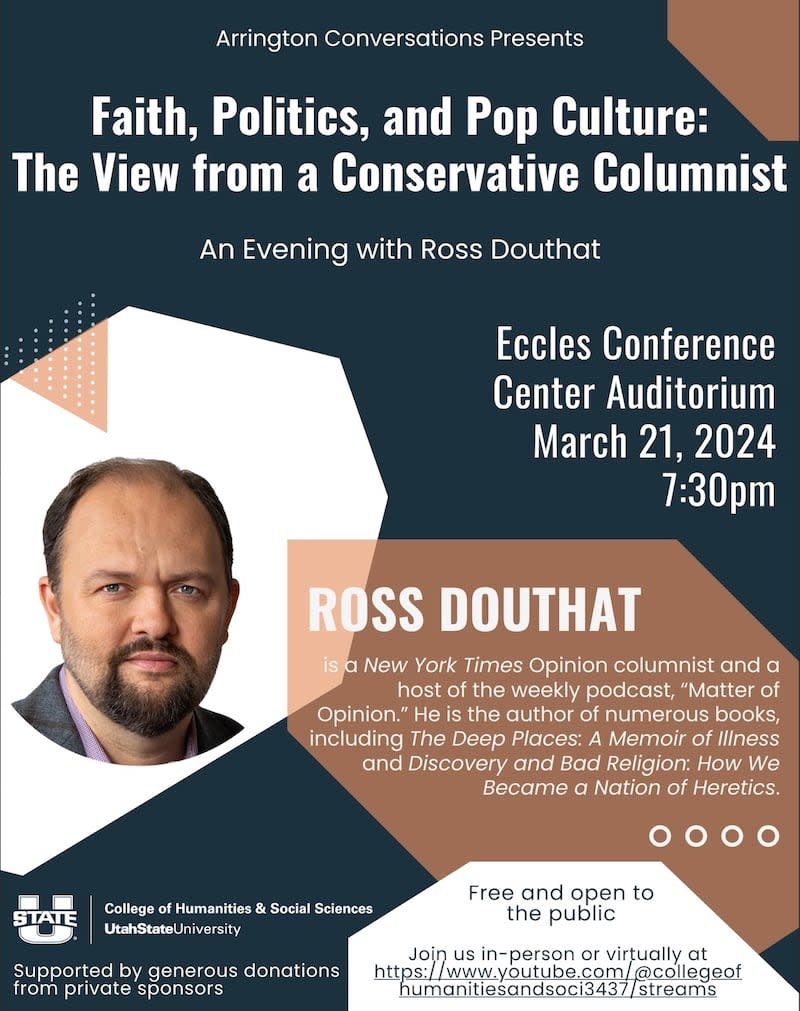

Douthat has written for the world’s largest newspaper since 2009 and is regarded as their most religious conservative voice. He is the author of numerous books, including “Bad Religion: How We Became a Nation of Heretics” (2013) and “The Decadent Society: How We Became the Victims of Our Own Success” (2020).

The columnist spoke before a mixed audience of students, faculty and community members at the USU Eccles Conference Center in Logan. While introducing the guest speaker, philosophy professor Harrison Kleiner cited one of Douthat’s former professors who described him as having a way of arguing important points in an “attractive and provocative way without trying to shock people.”

Prior to the event, Douthat told the Deseret News that the trend he is most concerned about in America today is the widespread “social and personal unhappiness and alienation, especially among young people.” Before the event started, Douthat took time to call his wife in Connecticut to see how their four children were before it got too late.

The goal of a newspaper columnist is “not just to offer opinion,” he said, admitting that it’s easy on a bad day to “sort of just default to here’s what I’m feeling about the news of the day” and “what’s making me angry.”

The aspiration of a good writer is to elevate discussion “above that level,” and “not just express what you yourself think, but marshal reasons why someone should agree with you, to make a case, consider opposing views, and to rebut them.”

Whence the media distrust?

Mason cited 2023 Gallup statistics that only 32% of Americans trust the mass media substantially to report the news in a fair way. “Why is this the case and what would it take to change it?”

Douthat suggested that the “long-standing conservative critique of the news media” was “basically correct.” Despite the aspiration of most news organizations to “capture the world as it actually exists without fear or favor and without partisan bias,” the challenge is that “almost everyone who works for those institutions is a political liberal.”

“Everyone comes into the world with their own set of biases and assumptions,” he acknowledged. Yet when any industry is dominated by “people who tend to share a certain set of biases … it’s going to easily alienate the people who have different assumptions.”

“This has been true for decades.” In addition to the “general disenchantment that Americans feel with almost every institution,” Douthat noted a newfound “class division between the media and the rest of America.” Compared to journalism 75 years ago, which was “more of a kind of blue collar profession,” news media today has become more of an “upper middle class intelligencia, postgraduate degree kind of profession.”

Douthat also highlighted the struggles of the local daily newspaper in the midsize American city, which had been a “key civic institution” throughout the second half of the 20th century and “the main way that people interacted with the news.”

Those local papers “had to be fairly politically neutral to sell ads” across the state, he said. “Even if you thought it was too liberal, or you disagreed with it, it was your city newspaper and you had some connection to it.”

When the internet began threatening the “economic basis of that model of journalism,” it undercut the form of journalism that was “actually closest to people’s most people’s lives.” In its place, he said, the public was left with partisan and national media filling the vaccuum, along with new forms of media on YouTube.

“That local and midsized city connection was really important to journalism’s health and the public’s trust of journalism and we don’t really have a substitute for that in our current ecosystem.”

Religious vs. political identities

Douthat went on to speak of the value of belonging to a religious tradition that has a well-developed set of teachings that “do not map perfectly onto American partisan divisions.” The teachings of his Catholic faith, for instance, were roughly speaking “more economically liberal than republican, and more socially conservative than the democrats.”

“Partisan identification has basically replaced religious identification” in recent decades, he said, citing how comfortable people used to be 50-60 years ago with their children marrying someone from a different political party (if not from another faith). That trend is exactly the opposite today, with 38% of Democrats and Republicans in a 2020 Economist/YouGov Poll saying they would feel upset at the prospect of their child marrying someone from the opposite party.

For many people, this political identification is now “more primary in their lives, even if they are practicing a religion.”

That continues a trend, Douthat said, where “people are looking for salvation through politics — both from the left and right” and “investing messianic hopes” in various political leaders.

Compared to the era where there were many liberal republicans and conservative democrats, Douthat suggested the tighter sorting of parties creates a stronger partisan pull. And “as religion gets weaker and partisan polarization gets stronger, it becomes harder for people to think ‘I’m Catholic first, and Democrat or Republican second.’”

As a corrective, Douthat suggested identifying “one issue where you think your party is seriously wrong for religious reasons” — and being willing to say something like, “I’m a Democrat, but because I’m a Catholic, I think Democrats are wrong about this.”

“I think that’s a healthy discipline for people.”

Conservative fear

“The right of center coalition in 2024 is essentially a negative force,” Douthat stated — “united by a desire not to be governed by Elizabeth Warren, Kamala Harris, the faculty of Harvard University, the editorial board of The New York Times” and any other elites of “social, culture liberalism.”

“The Republican coalition is comprised of people who don’t want to be ruled by the liberals” and who fear a “consolidated progressivism” in which “universities, Hollywood, the media, the legal system,” become increasingly “militant ideological forces trying to impose a strongly left wing vision of the country.”

Douthat suggested “there’s no sort of affirmative agenda” on the right, outside of some sporadic attempts — with the main “glue” being “we don’t like wokeness, we don’t like where liberalism is, and we fear it’s consolidated power enough to vote against it.”

Social conservative Americans today, he said, represent the “fragmented remains of American Christianity,” many of whom feel an urgency to “build something new out of the places where religious faith is still potent and influential.”

But in his view, conservatism is “very much a rebuilding project as opposed to a preservation project at this point.”

The rise of post-Christian ideology

Mason cited a passage from “Bad Religion,” where Douthat argued that “America’s problem isn’t too much religion, or too little of it. It’s bad religion: the slow-motion collapse of traditional Christianity and the rise of a variety of destructive pseudo-Christianities in its place.”

“The elite that was once at least sympathetic to Christian ideas has become hostile or indifferent,” the passage continues. “And the culture as a whole has turned its back on many of the faith’s precepts and demands.”

Remarking on how all these trends seem to have gotten worse over the last decade, Mason asked, “How would you assess the state of faith in America these days?”

Douthat described a slight change of emphasis in how he sees things today, compared with a decade ago. Whereas in the past, he expressed concern with the seeming drift towards Christian heresies like narcissistic individualism, today, he’s seeing more impassioned embrace of unapologetically “post-Christian ideologies.”

In the recent past, we lived in a society that wanted to “move beyond traditional Christianity, but really wants to hold on to Jesus” — with, for instance, social liberals arguing that “Jesus was awesome and he was a modern 21st-century liberal” — connected with a “whole industry of people reinterpreting the New Testament.”

By contrast, many people today are not even “really trying to speak in a religious language or appeal to churchgoers.” Rather, he said, we are seeing popularized “a new sort of revolutionary, radical form of ethics” alongside “particular kinds of utopianism” and different forms of “deep pessimism.”

“At a certain point, people stop. They stop wanting to recruit Jesus,” saying instead, “Why do I care? It doesn’t matter to me if Jesus was a liberal or conservative, because I’m not a Christian anymore.”

“We’ve gone from a world where it was really important for people to hold on to Jesus in some form, to a world where people are pretty comfortable just sort of letting that part of their inheritance go.”

Helping despairing young people

Mason cited figures from Ryan Burge demonstrating plummeting religiosity among high school seniors in general surveys. “If Pope Francis or President Nelson from my faith called you in tomorrow, put these numbers in front of you, and asked, ‘What’s going on and what should we do about it?,’ what would you say?”

“The reason those teenagers aren’t in church,” Douthat suggested, is that parents aren’t committed to their faith. Kids go to church when their parents model that kind of devotion, he said.

“We overestimate how much faith is lost in college, and underestimate how much it’s lost in high school.”

Amidst the deepening sorrow of our times, Douthat encouraged believers to better articulate “the religious answer to this unhappiness” and to help young people see their faith as a vibrant response to a “crisis of meaningless and despair.”

“We are handing on meaning, and outside of this [religious] group, people are in despair. We’re handing you the antidote to cultural despair.”

Advice for non-believing parents

“It’s really hard to present religion effectively to a child, if you cannot even consider the possibility that it’s true,” Douthat said in response to a student asking how to pass along to children the benefits of a religious heritage if that tradition isn’t believed by the parents.

To those who recognize the sizable benefits of religion, Douthat’s advice is fairly direct. “No, actually atheism is incorrect. God exists, and you need to get over that hump” and seriously consider “the strong possibility that religion is describing something true.”

“It’s not intellectually crazy to think God might exist. Your atheism is not this brilliant penetration into the mysteries of the universe that makes you smarter than everybody else. In fact, you’re probably wrong about your atheism.”

“Join millennia of human beings in recognizing that the universe looks like it was made for a reason. We look like we have some privileged place in it. And we should be looking upward to God.”

Admitting that secular audiences aren’t always so receptive to this argument, Douthat reiterated a caution against religion becoming approached by anyone as simply a means to an end. “You have to have some openness to the idea that it is getting at something that is real and true in order to start getting those practical benefits.”

And for those trying to help children grasp the value of faith, he said you can’t explain you are “dragging them to church” because “studies say that your mental health will be incrementally improved.” Parents need to be able to say, “This is really important and connects to the meaning of the universe and human life” — thereby giving children in a faith community assurance that they are “doing something of ultimate importance on Sunday morning.”