Rooks: Will our children see palm trees in Kittery, Maine?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

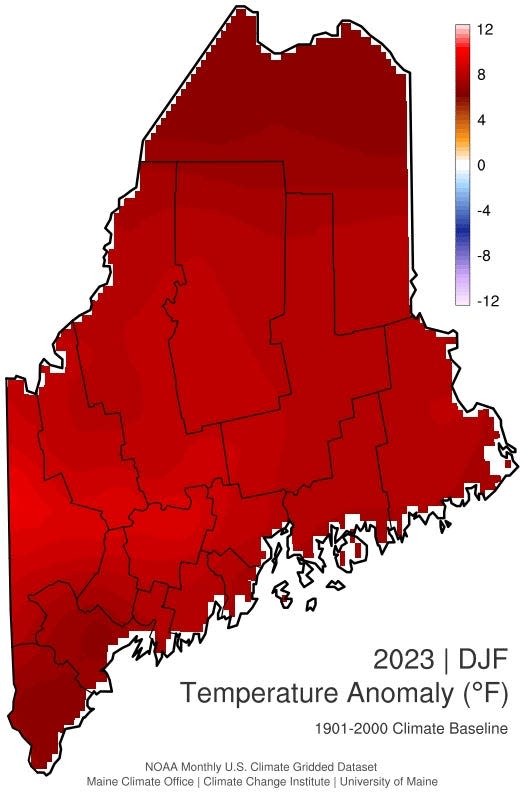

I’m looking at a map of Maine depicting the variance of temperatures from normal during “statistical winter,” which for some reason begins Dec. 1 and ended this year on Feb. 29.

The state appears to be on fire.

That doesn’t seem likely since the calendar is just turning toward spring, but there it is. Nor will March likely moderate the picture; since late January, we’ve had nothing but rain and lots of coastal flooding.

Those who’d hoped the shift from something resembling “normal” winter would be slow and gradual, something our grandkids could handle, got a comeuppance.

Yes, it’s only one winter but it’s hard not to think the Maine long-range climate forecast of “warmer and wetter” has arrived. There’s been plenty of precipitation – just not as snow.

The mean temperature for the entire state is nearly eight degrees above normal, with ice-out a month early. In my neck of the woods, it’s 10 degrees – astonishing.

In Sweden, where cross-country skiing was supposedly invented 5,200 years ago, they’ve been preparing for some time. The town of Torsby, on the Norwegian border, has built a mile-long concrete tunnel that holds the snow eight months a year.

In central Maine, machine-made snow on the Quarry Road trails in Waterville may be the best we can do, though even that could be a stopgap.

So we might want to consider something bolder, and bigger, to at least mitigate the unmistakable track of global warming. Otherwise, we could have palm trees in Kittery for some Mainers already alive – and see all our sand beaches inundated.

Starting with the dawn of modern state government – the Curtis administration, from 1967-75 – Maine’s been using general fund bond issues to invest in its future.

In the early years, there was a huge variety of purposes – water pollution control, new state parks and wilderness areas, funding the then-fledgling university system’s capital needs, fixing aging water and sewer systems, even buying school buses.

Following the Great Recession of 2008-09, bond issues began shrinking, and under Gov. Paul LePage were shut down entirely. LePage used a minor procedural provision – required signing of the warrant before it went to market – to block even bonds approved by two-thirds of the Legislature and a majority of voters.

He didn’t relent through the end of his administration in January 2019. Lawmakers last year removed that particular blockage, but it’s done nothing to revive interest in bond investments – rather the reverse.

Even LePage made an exception for $100 million in annual borrowing for highway programs, the result of his ill-advised move to end fuel tax indexing for inflation. The DOT funding gap keeps widening, with the state gas tax seemingly permanently frozen at 30 cents a gallon.

Gov. Janet Mills kept up that borrowing, then convinced lawmakers to bail out the Highway Fund by transferring $100 million a year from the General Fund, an unprecedented breach between two budgets that are legally separate.

So aside from a minor, $15 million bond for broad-band access in 2020, there have been no non-highway bonds during the Mills administration, with none in prospect.

Yes, unprecedented federal funds flowed during this period, but they’re one-time dollars with little long-term impact. When an inevitable economic downturn occurs, the state always cuts spending and investment. What then?

Bond issues are an important way to involve voters directly in making choices about the state’s future – a healthy alternative to the severely flawed referendums we’ve been subjected to lately.

Looking at the magnitude of climate change, it’s dismaying we’re not already addressing the enormous capital commitments it will require.

The idea we can pay for the entire new electrical infrastructure – generation, transmission, storage, charging stations, resilience – through monthly rate increases is a fantasy. Electricity is vital to all Mainers, and many can’t accommodate steep increases.

Nor can other traditional investments be ignored. The last university system bond was in 2018, and funding new buildings and labs through current revenues risks making tuition even more unaffordable.

Looking at transportation, relying entirely on roads and private vehicles can’t work. We should be investing in urban pedestrian paths and rural trails, making use of the idle state-owned rail network for trains, trolleys or whatever makes sense.

Such off-road transportation networks could dramatically reinforce denser, anti-sprawl residential and commercial development that may be our only hope of permanently reducing energy consumption and making housing affordable again.

Unless something changes, we’ll soon pay off almost the entire general fund debt. This isn’t virtuous, like paying off your home mortgage; instead, it demonstrates a lack of faith in the future.

If you don’t believe it, take another look at the map.

Douglas Rooks has been a Maine editor, columnist and reporter since 1984. His new book, “Calm Command: U.S. Chief Justice Melville Fuller in His Times, 1888-1910,” is available in bookstores and at melvillefuller.com. He welcomes comment at drooks@tds.net.

This article originally appeared on Portsmouth Herald: Rooks: Will our children see palm trees in Kittery, Maine?