Roman helmet looked like a ‘rusty bucket’ when it was found in UK. Now, it’s restored

Two decades ago, a group of amateur archaeologists unearthed a large metal object from a hillside in the English midlands.

The unassuming brown clump was not much to behold, and the archaeologists joked that they’d stumbled upon a “rusty bucket.”

But, the object turned out to be something extraordinary indeed: the fractured remains of a 2,000-year-old Roman cavalry helmet decorated with ornate patterns of silver and gold.

Uncover more archaeological finds

What are we learning about the past? Here are three of our most eye-catching archaeology stories from the past week.

→ Hidden tunnel network found at abandoned 800-year-old home in France

→Metal detectorist stumbles on 650-year-old artifact — and sparks a mystery

→ Ancient Roman ruins found in Germany help solve 140-year-old mystery, photos show

Known as the Hallaton Helmet, the piece of history has undergone years of restoration work, during which it has been “painstakingly pieced together.”

Now, the refurbished headgear will be displayed at the Harborough Museum in Leicester, located about 100 miles northwest of London.

Restoring the helmet

The fragmented helmet was found alongside a trove of coins and pig bones as part of a shrine dating to around 43 A.D., according to museum officials. Made from silver and adorned with gold leaf, it would have been worn by a high-ranking Roman cavalry officer.

Among its pieces are a helmet bowl — which would rest on the wearer’s head — seven cheekpieces, and dozens of other fragments.

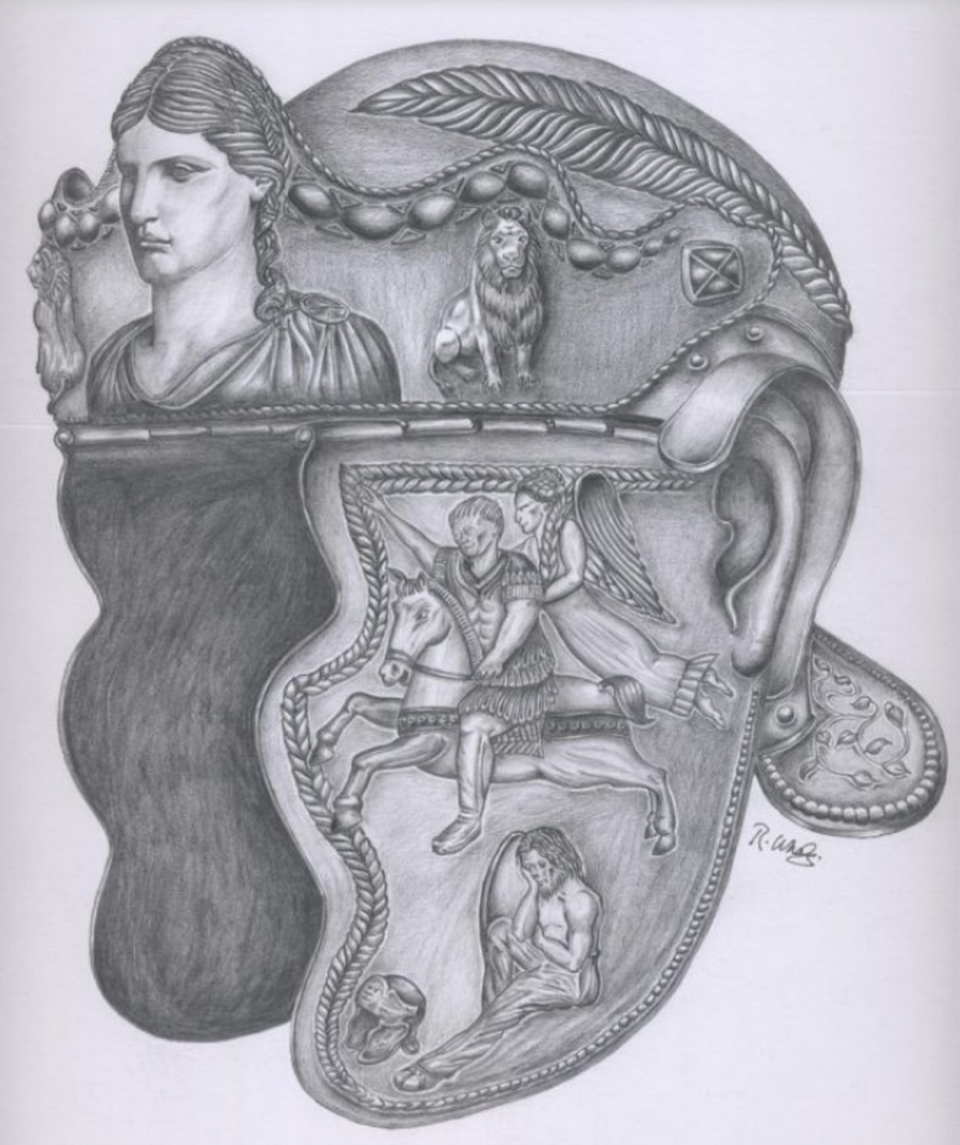

The cheekpieces portray a Roman emperor riding on a horse in front of the Roman goddess Victory, the equivalent of the Greek goddess Nike. Beneath the horse is a “cowering figure,” potentially representing a native of Britain.

The browguard, which would cover the wearer’s forehead, is emblazoned with a female figure, likely a Roman goddess, and possibly multiple lions.

Because the helmet pieces are so delicate, museum conservators opted to make 3-D scans of the remains in order to learn more about how to piece it back together.

These scans were used to create a gleaming replica, which was made of resin and plated with silver coated in gold, officials said.

The original helmet is also now 80% complete, and empty spaces have been replaced in order to strengthen the ancient headgear.

“There has also been a lot of behind the scenes work from the staff in the Museum Service, who have created lots of content to tell the story of the helmet and its discovery,” local official Christine Radford said in the museum release.

“This re-display would not be possible without the amazing conservation and reconstruction work which has been undertaken,” Radford added.

Roman Britain

At the time the helmet was in use, the Roman Empire was in the early stages of colonizing Britain.

Emperor Claudius launched one of the first invasions of Britain in 43 A.D., setting off decades of conflict that led to wide swaths of the island falling under Roman rule.

The Romans occupied parts of the island for more than three centuries, building military forts, roads and their form of centralized government.

Throughout this time, the elite members of society assimilated to Roman culture.

But most of the native population became “Romanized only to a limited degree,” according to research from the British Museum. Occupying the countryside, they lived in Iron Age homes, spoke Celtic and used farming equipment that predated the Romans.

Lampshade from Nazi concentration camp is ‘certainly human skin,’ forensic report finds

‘Radical’ letter found hidden in Shakespeare’s house in 1770. Now author is revealed

Hidden tunnel network found at abandoned 800-year-old home in France. See inside