The Return of Polynesian Pop

I walk onto the dark sand with my sandals dangling from one finger. The mai tai has gone straight to my head. It's been decades—four, in fact—since I stood here watching the waves break blue in the lights from the Waik?k? hotels, since I saw the black bulk of Diamond Head against the night sky. I know things have changed: The Tahitian Lanai is gone; the Polynesian Palace is gone; Don the Beachcomber, gone. As kitschy as they could be, it's hard not to feel nostalgic about the lost landmarks of the midcentury aesthetic known as Polynesian Pop.

Myself, I was late to the beach party. By the time I arrived as a college student in the late '70s, the bamboo torches and flaming Scorpion bowls were sputtering out. But I loved what remained.

And while tastes changed over the years, that golden, goofy era still has a powerful pull—and not only on me, it turns out. These days, Honolulu is awash in nostalgia. Mixologists are crafting complex homages to classic tiki cocktails. Architects, designers, and artists are finding inspiration in midcentury tropical mod. Vintage aloha shirts, souvenir mugs, and hula nodders are hot items at island thrift shops. Elvis may have left the l?'au, but Polynesian Pop lives on, drawing me back to my old Honolulu haunts to honor the old—and celebrate the new.

It's tricky to adore something that felt Hawaiian to me in my youth but in fact was anything but. (Some islanders were and continue to be offended by the secular use of sacred images such as carved tiki idols.) The movement didn't even begin in the islands, but in California. In the 1930s, two rival restaurants, Don the Beachcomber in Hollywood and Trader Vic's in Oakland, set off a mainland craze for rum cocktails and faux-Polynesian decor. It took a decade for those chains to open in Honolulu, bringing "back" to Hawai'i a version of itself. The cultural graft, an idealized exoticism of the South Seas, thrived. The bars spawned similarly themed restaurants, nightclubs, and hotels; when improved air travel in the early 1960s made the newly minted 50th state more accessible, tourists descended, expecting the Bali Hai of their dreams. Waik?k?—Honolulu's beachy neighborhood that formed the epicenter of the archipelago's tourism—was eager to please.

What better place to begin to reconnect and examine this legacy, I think, than at Waik?k?'s emblematic Royal Hawaiian hotel? A glamorous (and stunningly pink) resort since 1927, the hotel built a new beachfront bar in 1953 and commissioned Trader Vic's Victor Bergeron to craft a signature cocktail for it. Tweaking a recipe he'd served since 1944, Bergeron created the pineapple juice–based Royal Mai Tai, which quickly became the island standard. And that is precisely the drink I've just finished at that very bar, watching the surfers catch their last rides of the day, before heading down the beach, sandals in tow.

Then it's off to another Polynesian Pop landmark, the International Marketplace. The original Marketplace was a landscaped, thatched-roof maze of Pacific Island–themed shops and legendary nightspots opened in 1957 by Donn Beach, the founder of Don the Beachcomber. Inside the three-story open-air luxury mall that replaced it last year, I spy the Marketplace's landmark—a giant banyan tree—and am swept back to the 1970s. I bought a puka-shell necklace (was there anything cooler?) in the shopping bazaar shaded by these very branches. For a moment I am 19 again—salt in my hair, sun-kissed, in love with everything this tropical world offered my Boston-bred soul.

WATCH: A Perfect Weekend on O'ahu

The sweetly ramshackle kiosks and storefronts were torn down, but the tree still stands, hemmed in now by incongruously luxe neighbors: Tesla, Brunello Cucinelli, Christian Louboutin. I seek comfort at a new bar in the Marketplace I've been told pays homage to Donn Beach. It's called The Myna Bird, a nod to the chattering black bird (and pesky invasive species) that greeted patrons at Don the Beachcomber and to Michael Mina, the San Francisco restaurateur who opened the bar and other eateries in the upscale food court. I'm wary on approach, but the little bamboo bar has an elaborate throwback cocktail menu and theatrical bartenders serving drinks in great-looking tiki mugs. I feel my resistance melting. And when I taste my Low Tai'd—made with local K? Hana agricole rum and Velvet Falernum liqueur (one of Beach's secret ingredients)—I'm soothed. And feel the stealthy grip of nostalgia once again.

Is it possible that everything old can be new again? I head to once-dingy K?hi? Avenue, lately the focus of developers for its ripe-for-renovation midcentury buildings, to the new LayLow hotel, my Don Draper–worthy digs. Its Hawaiian Modern decor—low sofas, bamboo hoop chairs, rattan ottomans—is inspired by the work of Vladimir Ossipoff, the Russian-American architect best known for his works in Hawai'i. On my balcony overlooking the Waik?k? lights, I strum a few notes on a ukulele (every guest room comes with one) and marvel at the reverberations here.

In the morning, I set out to shop, looking for vintage and modern takes on Polynesian Pop's best-loved icons. Stop one: Bailey's Antiques and Aloha Shirts, a low-rise pink stucco building almost a half-mile inland from Waik?k?'s east end, packed to the rafters with more than 15,000 aloha shirts—from $10 hand-me-downs to coveted, rare 1940s and "50s classics that can fetch $1,000 or more. The earliest aloha shirts date to the late 1920s, when Honolulu tailors stitched them using Japanese kimono fabric. By the mid-1930s, local textile designers and manufacturers were creating their own with homegrown tropical prints.

"Knowledge is king in this business," says David Bailey, the shop's 73-year-old ponytailed owner, who began amassing his shirt collection at swap meets in the 1980s. He offers some vintage-spotting wisdom: Coconut-shell buttons, double-needle seaming, and yellowed embroidered labels are hallmarks of authentic midcentury shirts. I eye a rack of garish "60s and "70s models that range from $40 to $200. "Good investment," he says. "There's room for appreciation with those." For a moment, I fantasize about cornering the market on tropical-mod threads, going from Etsy to bricks and mortar, hauling my husband to Hawai'i for our next chapter as retail gurus of Polynesian Pop. The islands do that a person—make you crazy for a way to stay.

Next, it's pure collectibles at Surf 'N Hula Hawaii near the Queen Theater in Honolulu's Kaimuk? neighborhood. The shop is a Technicolor compendium of Hawaiiana: vintage matchbook covers, airline bags from Pan Am and Hawaiian Airlines, hulagirl lamps, porcelain bobbleheads, culturally questionable prints of jolly Hawaiian children, and even full-size surfboards. I hear that local celebrity chef Ed Kenney bought a wooden spoon here that he uses to make risotto, which feels like a blessing on the shop's complex abundance. I'm tempted by a vintage longboard surfing trophy—just the thing, perhaps, for my mantel—but the realities of shipping costs (and the size of my mantel) assert themselves. I leave with a geologist's vision of the strata of Polynesian Pop and then, just around the corner, spot yet another layer: the just-opened Golden Hawaii Barbershop, a pitch-perfect re-creation of a midcentury barbershop—vintage Koken chairs, barber pole, and all. Then it's off to Chinatown, perhaps the city's most up-and-coming retro haven.

My first stop is Roberta Oaks's airy little boutique in the heart of the revitalized shopping district. Oaks, a lanky 38-year-old Missourian who moved to Hawai'i in 2004, taught herself to make clothes on a garage-sale sewing machine. The hobby blossomed into a business when, on a whim, she put out a rack of her funky reconstructed vintage dresses at an art show and sold them all. Oaks, a fan of midcentury design (she recently sold her 1969 Valiant), converted her workroom into a retail shop in 2009, and shortly after switched her focus to menswear. "I wanted to do aloha shirts, something fresh," she says. "I got my ideas from watching downtown businessmen walk by." Her line of slimmer-fit shirts sell out regularly to a younger market looking to blend nostalgia with the fitness-forward silhouettes of modern life. I imagine Draper himself, were he back in Honolulu for a 2017 walkabout, seeing the future in it all. And buying from Oaks, as well.

The new Turks of Polynesian Pop here in Chinatown are all making savvy plays on what stole a nation's heart more than a half century ago. Sig on Smith, a new pop-up shop open only on Fridays, sells special-edition shirts from Sig Zane Designs, a beloved Hilo-based designer of hip, clean-lined prints based on Hawaiian culture. Tin Can Mailman is a gussied-up version of Surf 'N Hula, crammed with midcentury Polynesian Pop ephemera, including menus, ads, and matchbooks. Barrio Vintage, a sunny shop with a trove of bright "60s and "70s tropical wear, confers the resurgent power of the bold and the brazen.

That evening, I stop in for a drink at Arnold's Beach Bar, a cheap and cheerful tiki dive with potent $5 drinks, hidden in an alley off Waik?k?'s main drag. Then I walk up K?hi? to the Surfjack Hotel and Swim Club, with its easygoing 1960s cabana vibe. At Ed Kenney's Mahina & Sun's restaurant, just off the hotel's courtyard pool, I settle onto a banquette upholstered in a vintage Tori Richard aloha-shirt print and dive into Kenney's locally sourced comfort food: Kualoa Ranch oysters, ahi tartare on risotto cakes (I know where you got that spoon, Ed), dark-chocolate butter mochi.

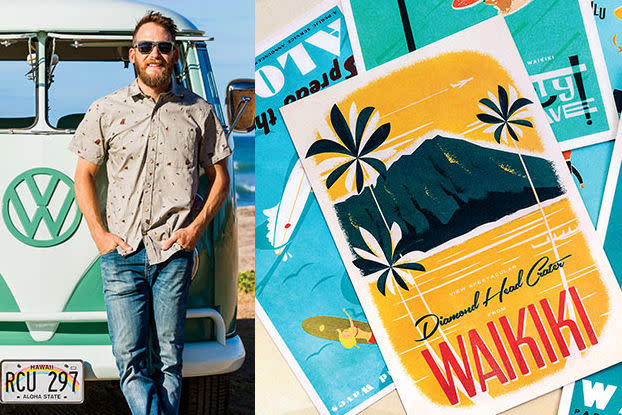

On my last day, I dig a little deeper to meet the artists who are driving the new aesthetic. I head out west of Honolulu to Ewa Beach and meet 36-year-old graphic artist Nick Kuchar, whose travel prints caught my eye in The GreenRoom, a Honolulu surf- and beach-art gallery. He tells me his first piece was created in 2010 at the request of his wife, who wanted some vintage-inspired artwork to hang on their wall. Eventually his beachy, desaturated prints gained a following through an online shop; Hawaiian, Japanese, and European art galleries; and collaborations with Patagonia, Walden surfboards, and others. When he gets stuck on a project, he drives his turquoise 1964 VW bus to the beach and goes surfing. "I try to stay true to what I like," he says. It feels like a mission statement with value far beyond the realm of graphic design.

I leave the coast and drive into the hills of Makakilo, where Mike "Gecko" Souriolle makes tiki mugs and Polynesian Pop art sought after by international collectors. The soft-spoken, Philippines-born 48-year-old conducts business in a bungalow he built with salvaged pieces from Trader Vic's and the Hawaiian Hut, a Polynesian-revue nightclub that went dark in 2008. Gecko (one-name monikers are standard in the tiki-artist world) shows me some spectacular recent work, including two intricately carved surfboards he found abandoned on the North Shore.

Gecko has famously created carvings and mugs for La Mariana Sailing Club, O'ahu's last original tiki bar and a de facto museum of shuttered landmarks from that golden age. On the shores of the Ke'ehi lagoon, a few miles west of Waik?k?, it's the perfect place to end my tour. From my marina-side seat, I see koa tables from Don the Beachcomber, carved totems from Sheraton's Kon Tiki room, woven lauhala matting from the Tahitian Lanai, puffer-fish lamps from Trader Vic's. Some of the older patrons look like they may themselves have been fixtures at those places back in the lovely, palmy days. The dark-rum floater in my mai tai sloshes over a bit as I lift the glass. I pause to steady it and give a silent salute to the palaces and patrons of Polynesian Pop, and to my former puka shell–wearing self. We are gone; we are here. We are right at home.

GET HERE

Several airlines fly nonstop from major cities into Honolulu's Daniel K. Inouye International Airport.

STAY HERE

The landmark beachfront, 528-room Royal Hawaiian, a Luxury Collection Resort, celebrated its 90th birthday in 2017. Rates start at $385. The breezy, midcentury-mod, 251-room LayLow, part of Marriott's Autograph Collection, is a five-minute walk from Waik?k? Beach. Rates start at $299. For cheeky retro-cool (and Ed Kenney's food) a few blocks from the beach, check in at the 112-room Surfjack Hotel & Swim Club. Rates start at $187.

DRINK HERE

The Mai Tai Bar at The Royal Hawaiian serves seven versions of its namesake cocktail. The Myna Bird at the International Marketplace divides its extensive drink list by region; try the Low Tai'd and the Splintered Paddle, from the Pacific Rim collection. Arnold's Beach Bar & Grill serves up $5 mai tais all day. No, your GPS is not wrong: The 60-year-old La Mariana Sailing Club really is in a forlorn-looking industrial area, but the mai tais, Zombies, and epic tiki decor make it well worth the hunt.

SHOP HERE

Bailey's Antiques and Aloha Shirts is the world's largest trove of vintage shirts in a wide range of prices. Surf 'N Hula Hawaii has several rooms of colorful island collectibles and antiques; Roberta Oaks sells sharp-fitting aloha shirts and easy-to-wear day dresses, plus island-made accessories and home goods. Sig on Smith, open Fridays only, is Sig Zane Designs's first shop on O'ahu. Tin Can Mailman is jammed with vintage Hawaiian books, clothing, and collectibles. Barrio Vintage curates a changing inventory of men's and women's tropical wear. The GreenRoom Hawaii gallery in the International Marketplace showcases surf- and beach-inspired artwork.

Meg Lukens Noonan is the author of The Coat Route: Craft, Luxury and Obsession on the Trail of a $50,000 Coat (Spiegel & Grau), a globe-trotting exploration of high-end bespoke tailoring. She lives in New Hampshire.