Researchers Repurpose Cotton Candy Machines to Make Blood Vessels ... And There Goes Your Sweet Tooth

Artificial organs have been an important part of science, not to mention science fiction, since the late 1800s, but since the invention of the 3D printer, the medical field has been buzzing with the exciting possibility of being able to print artificial organs. However, researchers continue to face one major problem: how to build in functional blood vessels that feed the tissue the blood it needs to survive.

In his lab at Vanderbilt University, mechanical engineer Leon Bellan is using good old-fashioned cotton candy machines to attempt do just that. If his team succeeds, these cotton candy-made capillaries could be used in everything from skin grafts to breast reconstruction.

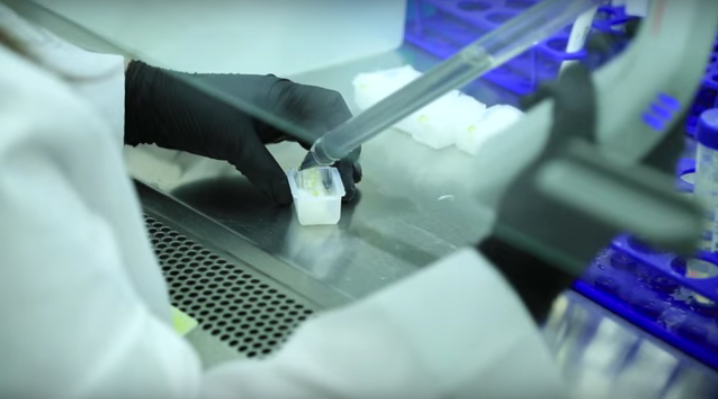

Here’s how it works. Lab technicians make real, live (delicious) cotton candy in the kind of machine you might pick up at Target. (Don’t scoff! Anyone who has worked at a carnival will tell you it’s not as easy as it looks.) Also, maybe don’t eat this cotton candy, since it’s mixed with a special polymer that helps it keep its shape.

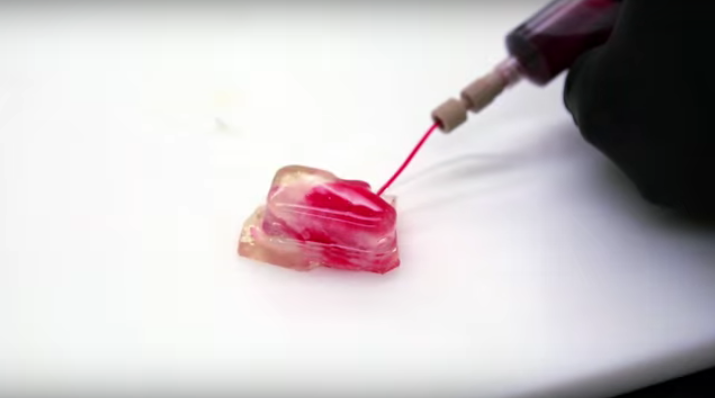

Once they’ve spun a delicate spool of candy wisps, they place it in a mold and pour gelatin over it. Once the gelatin has set, they change the PH balance in the mixture and the candy fibers dissolve, leaving behind a maze of tiny of channels that uncannily mimic capillaries. Each channel is about one-tenth the size of a human hair.

Then, lab technicians line these channels with human cells — grown in the lab — carefully enough that they don’t block any passageways. This is currently the trickiest part of Bellan’s research.

But if he succeeds, not only could Bellan’s work solve a major obstacle in artificial organ research, it could help make this medicine and research more affordable.

Equipment in Bellan’s industry can cost up to millions of dollars, but his team pays only $40 per cotton candy machine, and gelatin is a highly affordable material as well.

Bellan hopes that taking some of the cost out of research and production will help make lifesaving medicine more accessible and change the future of tissue engineering.