Residential Assistance for Families in Transition adjustments leave families in limbo

Editor's note: This story was updated March 21, 2024, to correct the name of the state program, to clarify a statement about the "legitimate need to move" standard and to correct the number of households serviced through the program and number of applications since the pandemic. The story was also was updated to add the program's current average benefit.

Anna Smith applied three times to the state’s Residential Assistance for Families in Transition program — before, during and after the COVID-19 pandemic — with the intention of “saving her two kids and her life.” Little did she anticipate the outcome would take a detour.

January marked the third rejection for the 28-year-old Springfield resident.

The Massachusetts Executive Office of Housing and Livable Communities turned down her request for assistance in relocating to a new home, saying that their mission has shifted back to include helping both homeowners and renters. Because renters must prove a “legitimate need to move,” for example, an inability to pay rent or a threatened eviction by their current landlord, Smith said she fell short of their standards.

“It’s not like it was during COVID,” said Smith, who was fired from her job in a restaurant in 2020 and relocated to a new, but “horrible,” home after reapplying and using her rental assistance voucher. “It was also really helpful when I first applied for it.”

Changes in state policy

The Healey administration’s state’s fiscal 2025 budget included an overall increase for the rental assistance program. But policy changes effective last July extended the program to homeowners and reduced the maximum amount of benefits a household can receive over a 12-month period from $10,000 to $7,000. In addition, successful applicants will no longer be eligible to receive reimbursement for any expected rental costs other than current debts or arrears.

“Generous benefits had to adjust to help more, because people in demands are increasing,” said Keith Fairey, chief financial officer of Way Finders, a nonprofit housing administrative organization that serves Western Massachusetts residents.

According to state data, the agency served approximately 57,000 households through the residential assistance program from the beginning of 2020 to the end of March 2023, with Springfield ranked as the first in need. Since the end of the pandemic, the number of applications has remained steady at about 3,500 a week.

“The application process was streamlined during that time,” said Smith, with fewer questions answered, zero paperwork required, and shorter approval processing times.

Landlords typically are unwilling to wait too long after they have discovered a property, and since the rental assistance application needs their signature and participation, many of them initially reject lessees who are funded by the state program, Smith said.

“It was so hard to even find a landlord who would sign,” said Smith, “and often they required you to pay three times the rent to hold the house.”

Among the least affordable states

Massachusetts ranks as the third least affordable state in the United States for housing, according to the Out of Reach 2020 report, behind only California and Hawaii. For 2020, an employee would need to make $35.52 per hour in order to afford a two-bedroom rental property at the fair market rent of $1,847, without having to spend more than 30% of their salary on housing.

However, as of May 2022, the mean hourly income was $36.83, and the median wage for all occupations was only $28.10, indicating that at least half of the households are unable to lead secure lives.

The fair market rent keeps rising.

“How much would they have to earn per hour if they are working 40 hours a week to afford an apartment?” said Kelly Turley, the Springfield area associate director of the Massachusetts Coalition for the Homeless, an advocacy team providing long-term solutions to poverty and homelessness.

Massachusetts is consistently unaffordable, Turley added.

Advocates claimed that even if the monthly subsidy was back to $10,000, it would still be insufficient for larger families or households in locations with more expensive real estate.

“Seven-thousand dollars is not enough,” said Turley.

An Executive Office of Housing and Livable Communities spokesperson said the annual benefit was $4,000 prior to the pandemic and that is a current average of requests in applications.

Residents are facing eviction

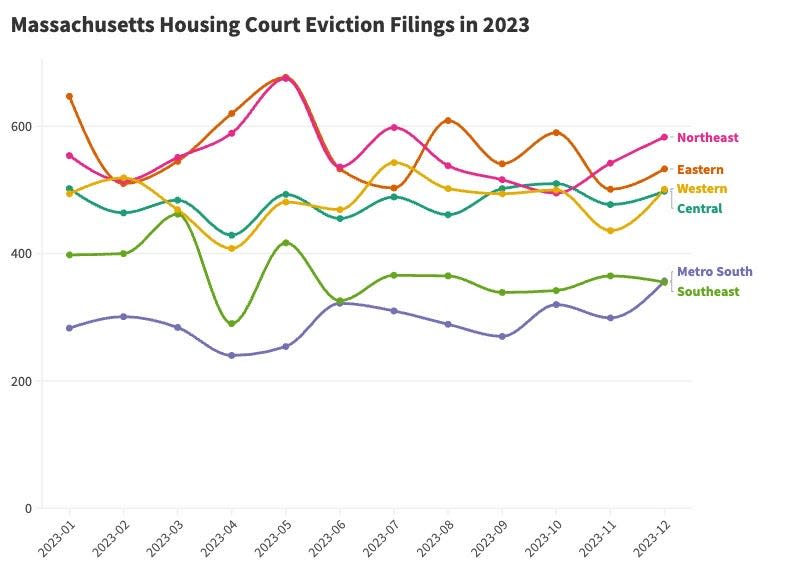

According to Turley, the majority of rental assistance applicants requested financing because they received notice to quit or eviction from their landlords; others were experiencing financial hardship due to layoffs. The Massachusetts Housing Court received 38,863 eviction filings in the last year, which is 70.5% more than in 2021.

“Can you imagine hundreds of people facing eviction every day when you sit in the Housing Court?” said Smith.

Massachusetts saw legislative efforts last year to make some eviction protections permanent, particularly through the re-enactment of and calls for extension of Chapter 257, a law originally intended to halt eviction cases for tenants who had applications for rental assistance pending. The goal was to protect renters and increase landlords’ rental aid payouts.

In 2023: Housing Court in Barnstable. What to expect if you have to go.

What happens, then, if the defendants’ outstanding balance is more than the current benefit cap could sponsor — say, $8,000 — and they do not have access to any other resources to cover the difference, Turley asked. Even though the rental assistance application is still pending, the judge would likely proceed with the eviction.

“So this is our concern right now, we do not believe the homeless prevention efforts could play a part by capping it at that amount,” said Turley.

Increasing investment should only be a solution to address the issues, she said.

More than 40 Massachusetts legislators, led by Rep. Marjorie Decker, D-Cambridge, sponsored the coalition’s proposal for Providing Upstream Homelessness Prevention Assistance to Families, Youth, and Adults, a measure currently before the Legislature’s Housing Committee after lawmakers agreed to extending the reporting deadline.

The bill would, according to Turley, forbid the Executive Office of Housing and Livable Communities from requiring tenants to obtain a notice to quit from their landlords and a utility company shut-off notice to be granted back rent assistance. It would also provide upstream access to benefits, raise the monthly funding for rental assistance benefit cap beyond $7,000 per household, and allow it to incorporate more elements of the previously federal-funded Emergency Rental Assistance Program.

Finally, the bill would maximize resources from the state program, HomeBASE, and other rental assistance programs.

Senate Ways and Means Chairman Michael Rodrigues, D-Westport, speaking to the coalition’s recent Statehouse lobbying day, said “the Senate will have a broad, comprehensive conversation on all the issues surrounding the emergency assistance program and providing services to the migrant families here in Massachusetts.”

The coalition plans to push for permanent implementation of the state rental assistance program and other homelessness prevention programs in the upcoming years to increase access for vulnerable residents. They also supported legislation that would fortify rental assistance programs and create a bill of rights for those who are homeless.

“We will continue to advocate to raise that cap, to go back to a minimum of $10,000, and to push for more flexibility to help people use RAFT more effectively,” said Turley.

The Cape Cod Times is providing this coverage for free as a public service. Please take a moment to support local journalism by subscribing.

This article originally appeared on Cape Cod Times: People who need rental assistance hammered by state's high rents