Q&A | Earth Day is Monday and this MUN chemist is hoping to change the future of plastic

Earth Day’s theme this year is 'Planet vs. Plastic.' (Tijana Martin/The Canadian Press)

Francesca Kerton, a chemistry professor at Memorial University, is trying to change the nature of plastic.

Her work is all about attempting to create new plastics that are less harmful to the environment.

From turning food waste and fish oil into new materials to testing out new plastics in different climates, Kerton is trying it all.

In advance of Earth Day on Monday, Kerton sat down with Weekend AM's Melissa Tobin to discuss her work and what people can do to improve their plastic recycling habits.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: How would you rate what you see when it comes to recycling plastics?

A: As humans, we're just a little bit lazy sometimes. I had a yogurt at lunchtime and it's just too easy for me to put that bit of plastic into the trash rather than take it home, clean it and put it in the recycling.

So I think we're doing better, but there's still a long way to go.

And in some cases, maybe our containers don't need to be made out of plastic. They could be made out of something else or something that would degrade in a landfill site.

Francesca Kerton is a chemistry professor at Memorial University. She works on developing new plastics, including a project that sees fish oil being turned into a more biodegradable form of plastic. (Memorial University)

Now, as a chemist, you've been working on improving plastic for our environment. Tell me a little bit about how you got into that work.

I'm a researcher at Memorial University and I've got a team of six graduate students.

These are students either studying a masters or PhD and they're all looking into using either waste from fishery and aquaculture or materials that can be got from forestry waste and discards and making that into new plastics.

How do you make the new plastic? What makes it new and improved?

One of the things that we're doing, which is pretty unique here, is that when we make a new plastic, we try to test it to see if it will degrade in the environment.

And we also try to look at the impact of temperature on that, particularly in Canada. It's all well and good if somebody discovers a new plastic in the Caribbean and it degrades there. We're a much colder climate and so we need to make sure that's going to work.

And we also need to make sure that when plastics break down in the environment, they're not yielding nano plastics or turning into something toxic that was actually worse than the plastic to start with.

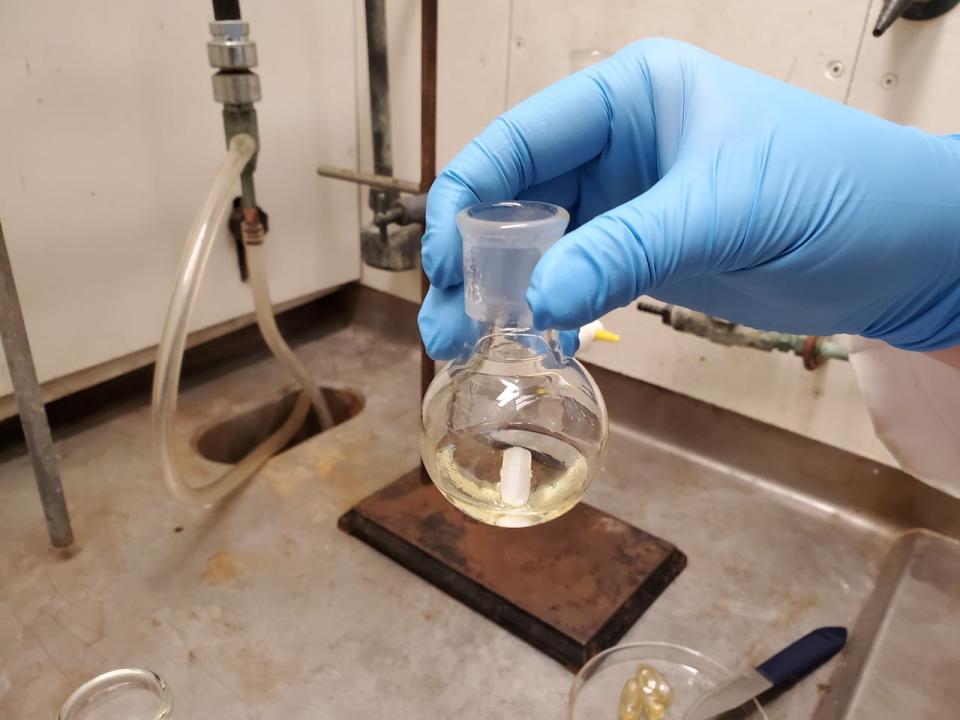

Fish oil extracted from fish heads and fish intestines is being used to try and develop a "green" plastic-like material. (Jane Adey/CBC)

You mentioned that you use waste from forestry, waste from food. Explain a little bit about some of those materials you're using.

We have to be really careful when we use food waste because, you know, if you open your trash can and there's food waste in there, it may be a bit stinky. And that's because of microbes that can go in there, and one of the reasons we want to use food waste is that microbes in the environment should be able to breakdown the plastics we make from food waste.

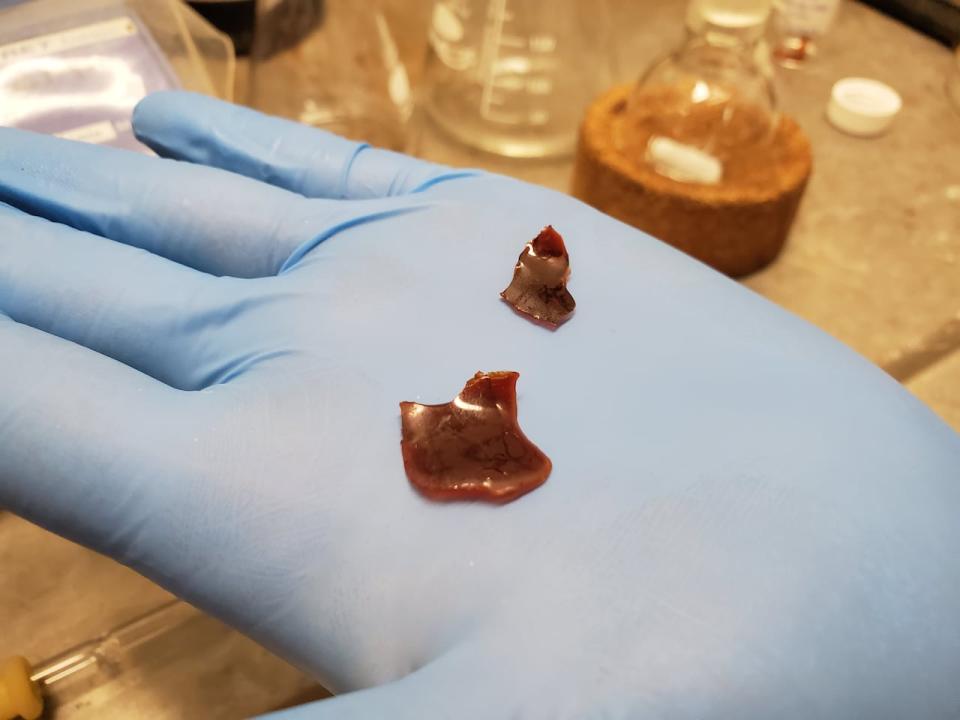

So we've been taking oils that can be obtained from fish bones. They're just like a pale yellow oil. And then we react it with some other materials and we get a sort of red film. And then we've tested it to see if it's biodegradable.

Plastics are something called a polymer and they're made-up of things called monomers, which are small molecules. And you can get these small molecules for example, from orange peels and other citrus fruits, or you can get them from pine needles, all sorts of places and make those into polymers.

And some of those polymers are probably a little bit more like our everyday plastics, but that research in our group is a little bit less far along. So lots of new exciting discoveries in the future.

This is what the fish oil looks like after it has undergone chemical reactions and before it's put in the oven to solidify. (Jane Adey/CBC)

So you're making these plastics, are you able to make products with them yet?

Where I'm a chemist, I'm more interested in testing to see if something works. And then in the future I would hand that over to an engineer to look at making bigger volumes.

Some of our research we have done on a larger scale, but usually for plastics, we're looking at about half a gram. So that would be maybe 1/4 of a teaspoon of the material, which is enough for us to test and figure out, 'OK, will it degrade or not?'

And then if we get a hit that [is] going to degrade, we can hand that on to somebody else to see if they're interested in scaling up.

But now and again people get in touch with us about some of our materials and that's super exciting. With our fish oil plastics, I had somebody get in touch from Portugal who was interested in the material and they manufactured soles for shoes, which are often made of plastic.

But unfortunately our plastic from fish oil, the one that we've really focused on a lot, that one absorbs water. And so you'd have a kind of spongy sole on your shoe. And so that's no good for that application, but we think it might be useful in other areas.

When a lot of us think about this it can be pretty daunting…. Especially when it comes to natural disasters, we're hearing much more about damage that's affecting all of our lives more directly. As a scientist who is helping to improve the products that we use in our life, how hopeful are you that what we're doing can fix our problems?

Scientists and engineers, they are naturally curious people and they can come up with all sorts of solutions. So I think I'm quite hopeful for the future.

Another area of my research is actually doing chemistry with carbon dioxide, one of these greenhouse gases that's causing climate change. And it's amazing what you can do with it.

This is how the fish oil looks once it has undergone chemical reactions and been heated in the oven. Francesca Kerton describes it as a "red film." (Jane Adey/CBC)

I mean, it's challenging, it's tough, but I think a lot of people, they thrive on that challenge. And it's amazing to see all the young people who are coming into this research area.

I'm going to be turning 50 this year. I'm not going to be able to solve all these problems. We need lots more young people to come in and do research as well and share their ideas with the world.

You get inspiration from your students as well, right?

Yeah, absolutely. My students are always coming up with ideas and knocking on my door and running in and saying, 'Oh, I just discovered this.'

There's a project where we work with fishbones and one of my students ran in and she was like, "Hey, you know, I was doing something with the fish bones and I made this.' It kind of looks like paper. It's not quite paper. And we're looking into that a bit more.

Monday is Earth Day. What is one way do you think you know from a scientist interview that we can all act to to respect our mother Earth?

I think a lot of it is down to making the right choices and trying to make a little bit of an extra effort.

Like I mentioned before, it's all too easy to be lazy and just put something in the trash rather than wash it and put it into the recycling.

And sometimes we've got to ask ourselves, 'Do we really need that new dress or shirt or pair of sneakers?' Because every time we buy something new, we're taking from the earth, and it's time that we start thinking about giving back.

Download our free CBC News app to sign up for push alerts for CBC Newfoundland and Labrador. Click here to visit our landing page.