How Russia sparked fears of an oil grab in British Antarctic territory

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The Russian polar research vessel Alexander Karpinsky drew little attention as it docked at Cape Town on its way back from Antarctica in February 2020.

At the time, Western governments were consumed by reports about the deadly coronavirus that was spreading from China to the rest of the world.

Yet the news carried aboard the blue and red-coloured Karpinsky was seismic in nature, both literally and figuratively.

In a statement following the ship’s expedition, the Russian geological agency Rosgeo said surveys had identified approximately 70bn tons of oil and gas buried beneath the Antarctic Shelf.

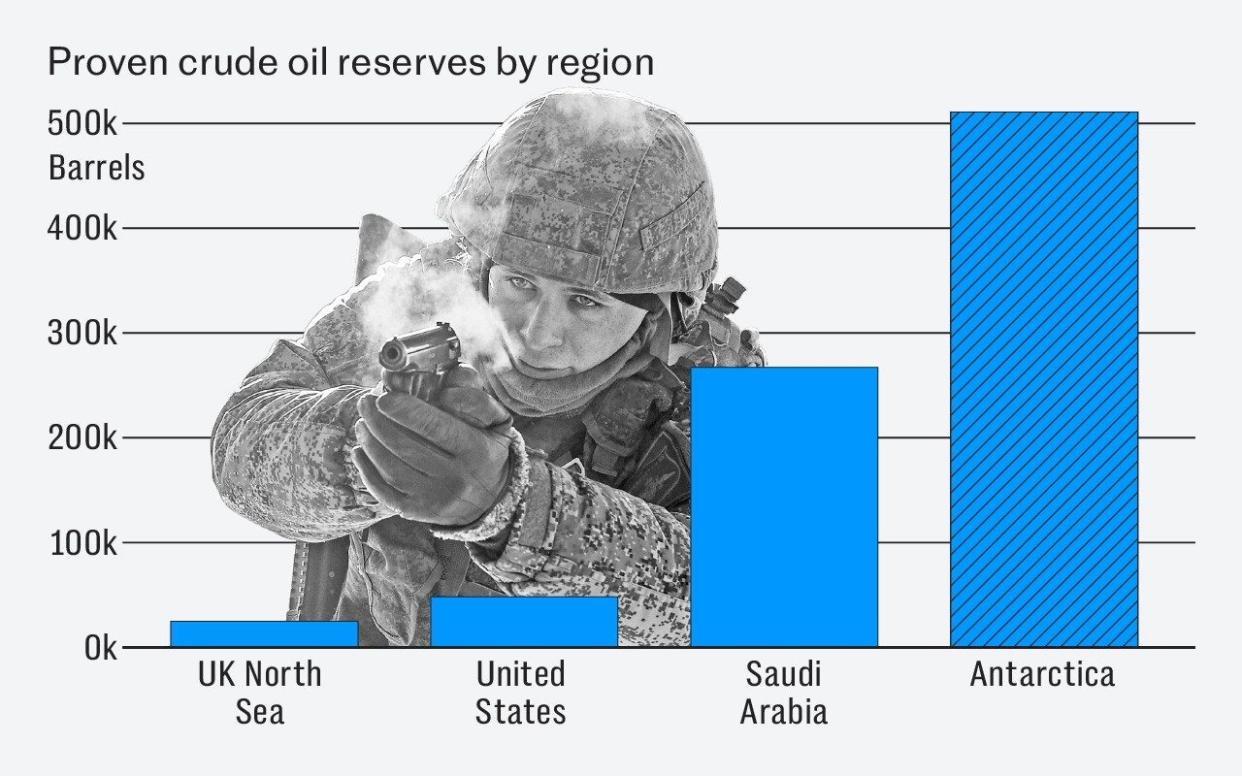

That is equivalent to more than 500 billion barrels of crude oil, enough to meet global demand for 14 years. It followed years of detailed surveys by Rosgeo, including ventures in swathes of the region that are claimed by Britain.

“The data obtained during the new expedition… will make it possible to substantially clarify our expectations of the oil and gas-bearing prospects of the Antarctic Shelf Seas,” noted Sergey Kozlov, chief geologist at PMGE, a subsidiary of Rosgeo.

Fast forward four years, however, and the West is finally taking notice of this startling discovery and its potential implications for geopolitics.

Last week MPs demanded answers about Russia’s “troubling” activities in the far south, grilling Foreign Office officials and a top government minister at a committee hearing.

Their intervention followed concerns that Moscow’s geological surveys may be a prelude to a resource grab, at a time when Vladimir Putin’s regime is being squeezed economically by Western sanctions.

Drilling for resources in Antarctica would represent a breach of the international treaty that has governed the territory for decades, which specifically bans “all activity relating to mineral resources, other than scientific research”.

And though Russia insists the surveys are scientific in nature, experts are increasingly concerned that they represent just one example of so-called grey zone tactics being employed by the Kremlin around the globe, designed to muddy the waters of acceptable behaviour.

“There is a worry that Russia is collecting seismic data that could be construed to be prospecting rather than scientific research,” said Klaus Dodds, an Antarctic expert and professor of geopolitics at Royal Holloway College, in a submission to MPs.

Dodds has also pointed to clashes between Moscow and other countries including the UK, including over fishing rights, the blocking of Russian base camp inspections and a row over the invasion of Ukraine during a 2022 annual meeting.

Fitting into this pattern, Russia’s oil and gas surveys appear to be “a conscientious decision to undermine the norms associated with seismic survey research, and ultimately a precursor for forthcoming resource extraction”, Dodds has written elsewhere.

Antarctica, which spans an area roughly 56 times the total landmass of the UK, is not currently governed by any one country, making it a giant and inhospitable no-man’s land.

This state of affairs dates back to the Antarctic Treaty, originally signed by 12 nations in 1959 as part of efforts to ensure scientific cooperation.

Seven made historical claims to territory – Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, New Zealand, Norway and Britain – while the US and Russia (then the Soviet Union) each reserved a right to make claims in future, without recognising those of others.

The British Antarctic Survey (BAS) is responsible for carrying out the UK’s scientific missions and maintaining a permanent presence that includes five research stations.

During the peak season for activity (winter time in the UK, when there is 24-hour daylight in Antarctica) the BAS also deploys the research ship RSS Sir David Attenborough to the region, allowing hundreds of researchers to get out into the field.

But today there are more than 50 signatories to the Antarctic Treaty, including big global powers such as China and India which are competing to set up their own infrastructure.

Dodds and other experts argue that containing Russia will require cooperation with these countries, many of whom feel that the treaty system has historically favoured the UK and other western European countries.

Already, some of these members have sided with Russia during disputes. At a tumultuous gathering of signatories in Berlin during 2022, the Russian delegation was denounced for flouting international law by invading Ukraine.

But China refused to endorse the criticism, warning other countries such as the UK not to “politicise” the Antarctic.

At the same time, the Foreign Office has been accused of complacency amid claims by officials that there is no evidence of malign intent from Russia.

Experts argue that the activities of Rosgeo’s ships such as the Karpinsky – and other infrastructure established by Russia – present a diplomatic dilemma because of their capability for both civilian and military purposes.

Rosgeo continues to maintain that its surveys are purely scientific.

During the committee session last week, MPs pressed Andrew Griffith, the science minister, and Jane Rumble, head of the polar regions department at the Foreign Office, over the “extremely serious allegations about Russian malpractice”.

But Rumble told them: “There isn’t any evidence that would point to a breach of the treaty. You would need different equipment between surveying and actual exploitation.

“But yes, we’re watching it very closely and Russia has been tackled on this before and assured [other Antarctic Treaty signatories] on multiple occasions that this is a science programme.”

There are also doubts about how realistic a resource grab by Russia in the Antarctic would be, given the generally hostile conditions.

To the fury of climate change campaigners, oil giant Shell at one point investigated whether it could extract resources from the Arctic region, also known as the High North.

But the company pulled out in 2015 after concluding it would be too expensive and risky.

None the less, Dodds believes the threat posed by Russia is concerning because of the state-backed nature of Rosgeo and the growing perception in Moscow that the Antarctic has a vital role to play in protecting its security interests.

He suggests that skilful diplomacy must be employed by London, including efforts to nail down more conclusively what kind of activities really qualify as “research” when it comes to exploratory oil and gas drilling.

With a meeting of the treaty participants due to take place in India later this month, the issue is almost certain to come up once again.