POWs housed on Eastern Shore, south Hampton Roads

OYSTER, Va. (WAVY) — The stillness of rural Virginia only adds to the scenery that is life on the Eastern Shore. But this land now covered in yellow Rapeseed hides ghosts from the battlefields of the 20th century.

Mike Holvick moved to the small Northampton County town of Oyster two-and-half years ago to a house built on what was once Camp Ettinger, which held German prisoners-of-war brought to Virginia beginning in the summer of 1944.

“Having that kind of history related to that place where you live is quite remarkable,” Holvick said.

Camp Ettinger was one of 23 World War II prison camps in Virginia housing 17,000 POWs — many of them in Hampton Roads.

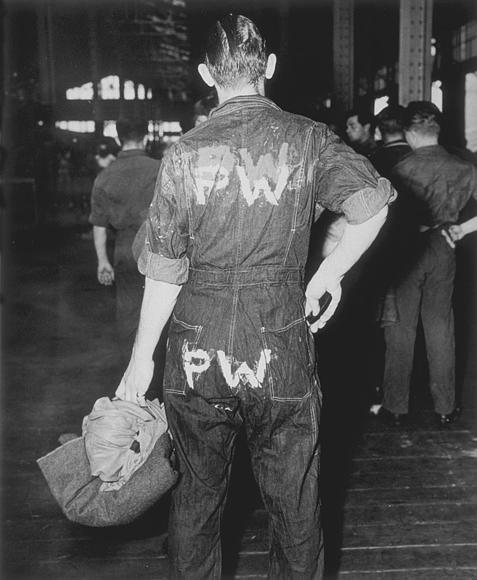

“We obviously started taking lots of prisoners, was not really sure what to do with them,” said Julie Spivey, a historian now living in the New Orleans area. “And because of the fact that we had so many men overseas, they decided to bring them to the United States and in our case, Virginia Beach and the surrounding Hampton Roads area and use them as a labor force to help us and the agriculture mainly.”

The German POWs on the Eastern Shore also became a local curiosity for those living in Oyster, outside of Cape Charles.

“People would take their Sunday trips to, we call it Route 600 now, or just 600. It’s one of our back roads,” said Andy Dunton, who works as a tour guide with the Cape Charles Museum. “And we’d go in, I guess, for lack of a better term, gawk at the prisoners that were inside the fence.”

And at least two went outside the fence.

A 1944 edition of the Eastern Shore News tells of two POWs who escaped Camp Ettinger. The article states they were recognized by the wife of a wounded American soldier and captured two days later. The Northampton County Sheriff said “they offered no resistance and were perfectly submissive.”

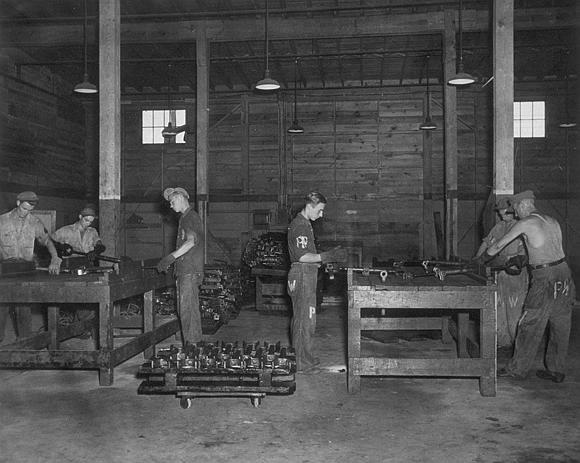

As a 10-year-old boy growing up in Pungo, in what was then Princess Anne County, Joe Burroughs remembers prisoners picking corn on the family farm for six hours a day, four days a week. They were each paid two dollars, 50 cents a day — half of what Americans earned. Burroughs recalled that the prisoners were closely watched.

“Oh, yeah. Whenever they brought them out with a truck, they’d have him in the back of the covered truck,” Burroughs said. “They’d have to get two guards, had rifles, automatic guns. And the guards told the landowners, ‘We cannot have them within 100 yards of a building.’ So when you put them in the field, you had to make sure you were away from a building, and they had to have a place when they walk down the road and come back.”

They were housed just off the road they helped build: Virginia Beach Boulevard, on the site of Willis Furniture and Mattress. Spivey received a grant award from the Virginia Beach Historic Preservation Commission to research German POWs. Her work led to a highway marker on Virginia Beach Boulevard in 2018 for Camp Ashby, which became the largest German prisoner of war camp in south Hampton Roads.

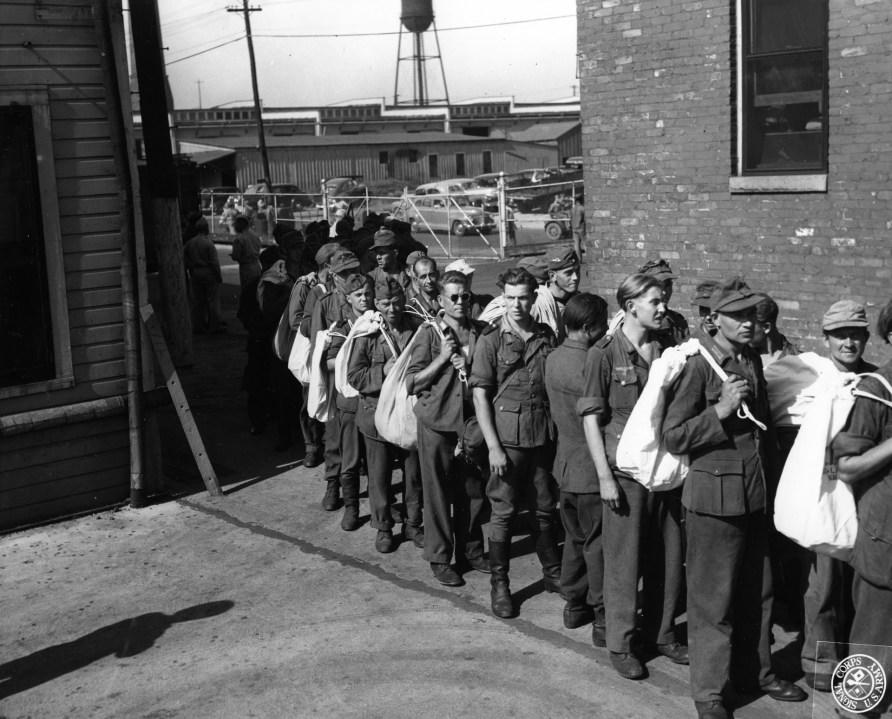

Six-thousand POWs stayed at Camp Ashby from 1944-through the end of the war. Many of them fought in North Africa under a man known as the Desert Fox, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel. Others were captured during the D-Day invasion.

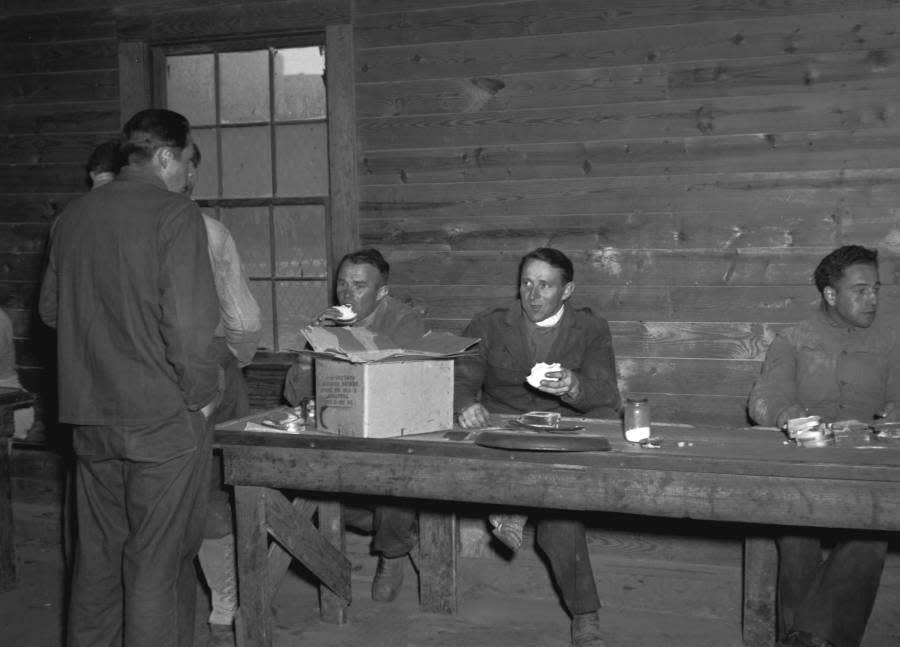

“They pretty much had every modern, convenience as you can imagine for the prisoners there. It was a very structured camp. The prisoners got up, they went to work,” Spivey said.

After an Allied victory, Spivey said the POWs were repatriated, and that many left Virginia with a new impression of American life because of “not what they had heard [and] not what they had been taught about us, but what it really was — individual freedom.”

In Newport News, Fort Eustis hosted a re-education center for German POWs with a six-day course in American democracy. But Spivey believes German POWs learned a lot from how an ideal of what America could be, a vision vastly different from that of Nazi Germany.

“I think what was more successful than the re-education program was the citizens and the Americans,” Spivey said. “And the way that they treated the soldiers when they got here, I think that had a profound effect on the German soldiers and their understanding of American life and the American way.”

More information

Read more about Camp Ashby in south Hampton Roads and Prisoners of America.

For the latest news, weather, sports, and streaming video, head to WAVY.com.