Pioneers paved the way for female students at the University of Michigan

GRAND RAPIDS, Mich. (WOOD) — The University of Michigan has a long and storied history. More than 200 years after its founding, it stands as one of the most prestigious public universities in the nation.

While the successes are often celebrated, the struggles are not. Founded in 1817, it took 36 years for the university to admit its first Black student — a man of mixed race who kept it a closely guarded secret and whose classmates thought he was white. It took 63 years to admit its first woman. Those pioneers have served as guideposts for generations to come.

Here is a look at the fight for the right to learn and the story of some of the women who made history in Ann Arbor and set a standard that proved women belonged in the classroom.

YOU GOTTA FIGHT FOR YOUR RIGHTS

In 1837, Oberlin College in Ohio became the first institution in the country to admit female students.

That same year, Michigan was granted statehood and the school that is now known as the University of Michigan moved to Ann Arbor. It was established under statute that the university was founded for “all persons who possess the requisite literary and moral qualifications” — a phrase that, in hindsight, highlights the flaws in the Board of Regents’ protocols.

Learn about Grand Rapids’ women legends through walking tour

For decades, Oberlin stood as the exception, not necessarily the leader, in the education sector. But it wouldn’t be alone for long. Public pressure, amplified by the end of the Civil War, demanded change. Historian Ruth Bordin explained why in her book, “Women at Michigan: The ‘Dangerous Experiment,’ 1870s to the Present.”

“A number of factors contributed to this explosion of women into higher education. First, the growth by mid-century of a public school system, not yet free but publicly subsidized, had vastly increased the need for teachers,” Bordin wrote. “By 1870, three out of five teachers in the United States were women. Not only were women considered better fitted than men for teaching, a nurturing profession, but also important was that women could be paid less.”

Outside employment opportunities and the women’s suffrage movement also played a role, along with the growing belief that more education benefited society as a whole. The Morrill Act of 1862 paved the way for land-grant institutions, which opened even more doors to higher education.

In Michigan, the push had been felt for years. In 1858, three women wanted to apply to Michigan. University President Henry Tappan insisted they be rejected, claiming that co-education would upset the natural order of the sexes.

“(Women students) will be something mongrel, hermaphroditic,” Tappan reportedly said. “We shall have a community of defeminated women and emasculated men.”

A citizen petition with nearly 1,500 signatures was presented to the Board of Regents in 1859, but with Tappan and enough like-minded thinkers on the Board, it fell flat. One of the regents called the idea of admitting female students “a very dangerous experiment,” serving as the inspiration for the title of Bordin’s book.

Meijer features local female artists for Women’s History Month

In 1867, the Michigan Legislature took action, adopting a joint resolution that women should be allowed to attend the publicly funded university, saying “the high objects for which the University of Michigan was organized will never be fully attained until women are admitted to all its rights and privileges.”

In January 1870, with a new president in place and two new members added to the Board, the university relented and formally allowed women to apply for admission.

MADELON STOCKWELL

Once the Board of Regents’ resolution was made public, Lucinda Stone rushed to share the news with her friend. Stone worked at Kalamazoo College and was an ardent supporter of co-education. She believed if anyone could live up to the academic rigors of the University of Michigan, it was her former student, Madelon Stockwell.

Stockwell had already attended K-College and Albion College and had earned a two-year degree while finishing as valedictorian. She watched as her male classmates took advantage of new opportunities, making the jump from K-College to Ann Arbor. Now, it was her turn.

Stockwell traveled to Ann Arbor to visit campus and take the entrance exams — tests that were allegedly much more difficult than the ones assigned to prospective male students. It didn’t matter. Stockwell passed them anyway. On Feb. 2, 1870, she made history as the first official female student at the University of Michigan.

It wasn’t an easy road. Just because the Board of Regents had changed its policy didn’t mean everyone loved the idea of co-education.

In a profile by the university’s Kim Clarke, Stockwell recalled a story from one of her first classes.

“In the days after Stockwell enrolled, a dog wandered into a classroom. Rather than shoo away the stray, the professor came to its defense,” Clarke wrote. “He invoked the regents: ‘We recognize the right of every resident of Michigan to the enjoyment of the privileges afforded by the University.’ The dog remained, given the same standing as women students.”

While history remembers her fondly, integrating the university all by herself, it doesn’t make the memories any less hurtful.

“This was Madelon’s world,” Clarke wrote. “A mix of cold shoulders and hot rhetoric, of mockery and mentors.”

Sign up for the News 8 daily newsletter

In a delightful twist, Stockwell fell in love while attending the university. Alphabetically assigned seating in one class put Stockwell next to Charles Turner. Within three years, both Stockwell and Turner had their degrees and they got married.

Fate wasn’t always kind. Turner was soon diagnosed with tuberculosis and developed breathing issues. The young couple moved to Colorado and southern California, looking for clean, dry air to help his lungs. He ended up dying from complications in 1880, just seven years after their wedding.

Stockwell never remarried and instead doubled down on her commitment to learning. She moved back to Kalamazoo and lived with her mother and stepfather. She was an active member of the Ladies Literary Association, gave presentations on Greek history and culture, painted, and even used her business savvy to buy and sell real estate, stretching her inheritance into “a sizable fortune.”

Honesty, candor at the heart of Betty Ford’s legacy

When she died in 1924, Madelon Stockwell Turner was worth approximately $340,000 — more than $6 million today. It was all dedicated to higher education. Part of her inheritance was sent to the University of Michigan to provide scholarships for women in the College of Literature, Science and the Arts. Albion College received a donation to build a new library, named after Stockwell’s parents.

But the real gift was the path that she blazed for women scholars.

“By the time of Stockwell’s 1924 death, 7,000 women had attended U-M and another 3,500 were enrolled on campus,” Clarke wrote.

DR. AMANDA SANFORD HICKEY

After dealing with health struggles as a child, Amanda Sanford knew she wanted to work in medicine.

While working to support her mother, the New York native found a job as a caretaker. That eventually led to a year of study at the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania and an apprenticeship under a prominent doctor at the New England Hospital for Women and Children.

In 1870, several apprentices received letters from the University of Michigan, encouraging them to apply to the school. Sanford took them up on the offer and headed to Ann Arbor.

Ceiling shattered: Anna Bissell broke barriers as America’s first female CEO

Women were now allowed to attend classes and even allowed to study medicine, but classes remained segregated. The university stated: “a large portion of medical instruction cannot be given in the presence of mixed classes without offending the sense of delicacy and refinement that should be maintained between the two sexes.”

Sanford focused on women’s health and pregnancy. Between her time as an apprentice and as a student, she had studied more than 800 cases of eclampsia. By the time she submitted her senior thesis, Sanford was considered one of the country’s most knowledgeable researchers on the pregnancy complication.

Because of her past studies, she earned her M.D. quickly. On March 29, 1871, she was presented with her degree — the sole woman in her class of 90 graduates — and the first woman to graduate with a degree from the University of Michigan. The historic moment was marked by her classmates with a hail of spitballs, fired from the gallery in protest.

She returned to Cayuga County in New York and opened her own medical practice. It eventually expanded into a hospital, one that included a separate facility just for pregnant women to receive more nuanced care.

She was named to the Cayuga County Medical Society and even named president by her colleagues, who said she “possessed a rare degree in the gifts of silence, deliberation and perseverance.”

Sanford, who got married in 1884 but continued to practice medicine, was also a political activist. She helped organize the Cayuga County Political Equality Club that worked with some of the country’s most popular suffragists, including Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

The Sanford House at U-M’s Bursley Hall is named after her. In its dedication, the university says: “(Sanford’s) name will be looked up to as a beacon of inspiration to the women who reside in Bursley Hall and remind them to persevere for equality just as she had dedicated herself to throughout her life.”

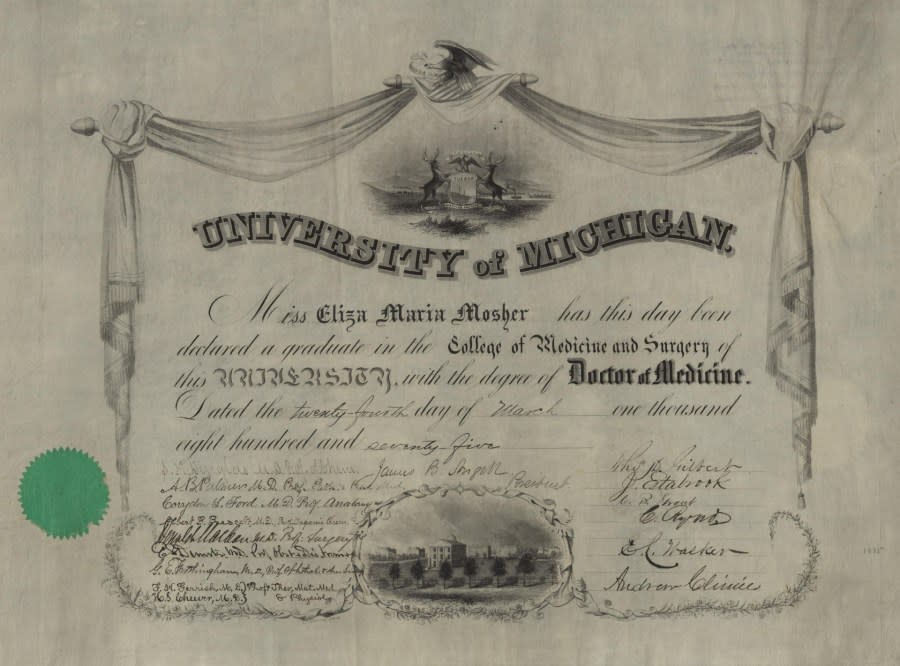

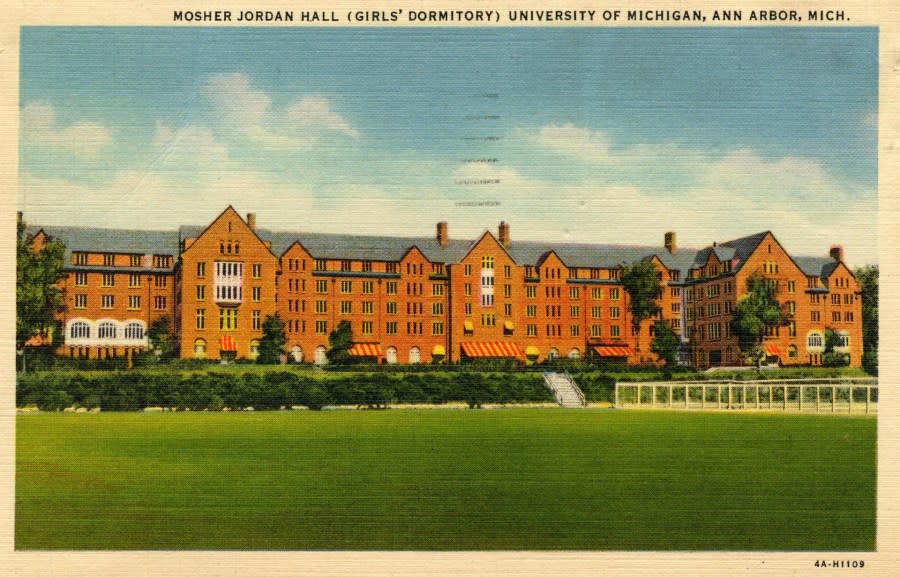

Dr. Eliza Mosher is photographed at her desk in 1925. She was the first female professor at the University of Michigan and the school’s first “Dean of Women.” (Courtesy University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library) Dr. Eliza Mosher was one of the first women to graduate from the University of Michigan. She received her M.D. in 1875. (Courtesy University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library) A postcard depicting Mosher-Jordan Hall, the first large dormitory for women on the campus of the University of Michigan. Construction finished in 1930. It was named after the first two “Dean of Women” at the university. (Courtesy University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library)

DR. ELIZA MOSHER

Just like Sanford, Eliza Mosher was from Cayuga County, New York. Mosher, who was eight years younger than Sanford, became a skilled midwife and got a job at the New England Hospital for Women and Children.

Like Sanford, Mosher took up the university’s offer to apply for admission. She graduated with her M.D. in 1875 and, like Sanford, returned to New York to open her own practice. The two even spent time traveling Europe together and studying new techniques.

WOOD TV8’s unique connection to Anna Bissell

While Sanford stayed committed to New York, Mosher moved around more. She served as the director for the Massachusetts Reformatory Prison for Women before spending a decade at a practice in Brooklyn, New York. In 1896, Mosher returned to Ann Arbor as the university’s first “dean of women.”

“As Dean of Women, she acted as a liaison to the 600 women at the university — an important role, as they were severely outnumbered by men,” the university profile reads.

Sign up for the News 8 weekly recap newsletter

She served as the director of physical education and the resident physician for the campus’ female students.

Mosher held the position for several years before returning to New York. Along with her usual work, she also studied posture, founded a national organization on proper posture and even designed a school desk and chair for children to encourage proper posture.

Mosher-Jordan Hall was established in 1930 in honor of Mosher and her successor as U-M’s dean of women, Myra B. Jordan.

For the latest news, weather, sports, and streaming video, head to WOODTV.com.