One Year After Hurricane Maria, We Are Still Picking Up the Pieces

Three days had past and still no word from my 80-year-old uncle, Tío Primitivo Rivera. Three days of no cell phone service. No electricity. No way of getting to him. No way of knowing if he was buried under his house with his roof peeled away like that scene fromThe Wizard of Oz. No way of knowing a thing. When Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico on September 20, 2017 it took everything with it and left those of us with relatives on the island feeling powerless.

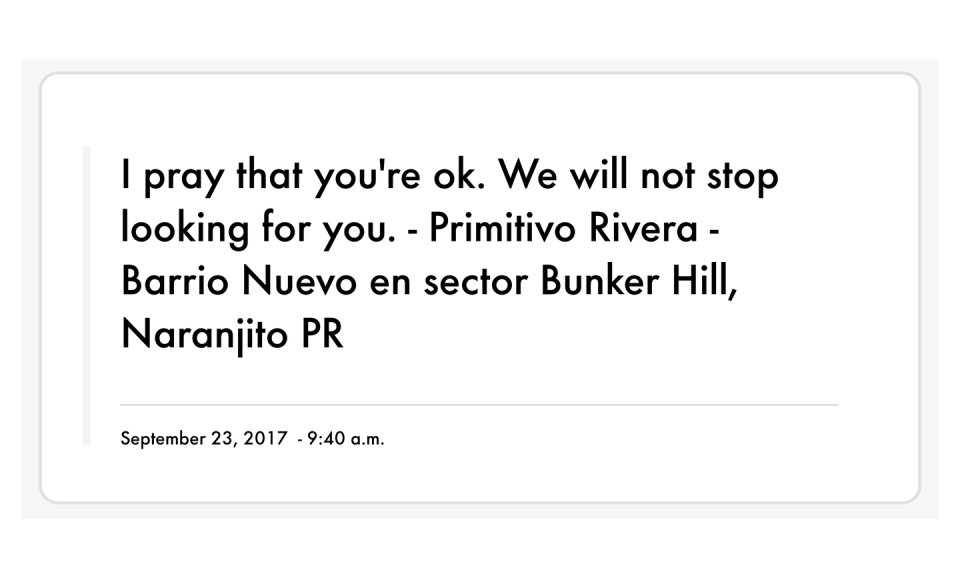

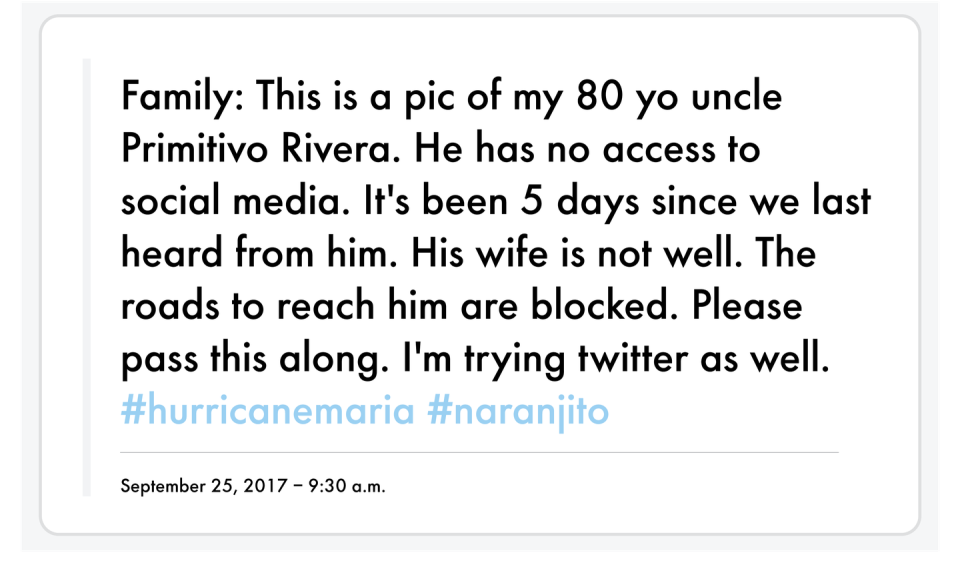

Back in the States, my family took to social media and began our daily posts.

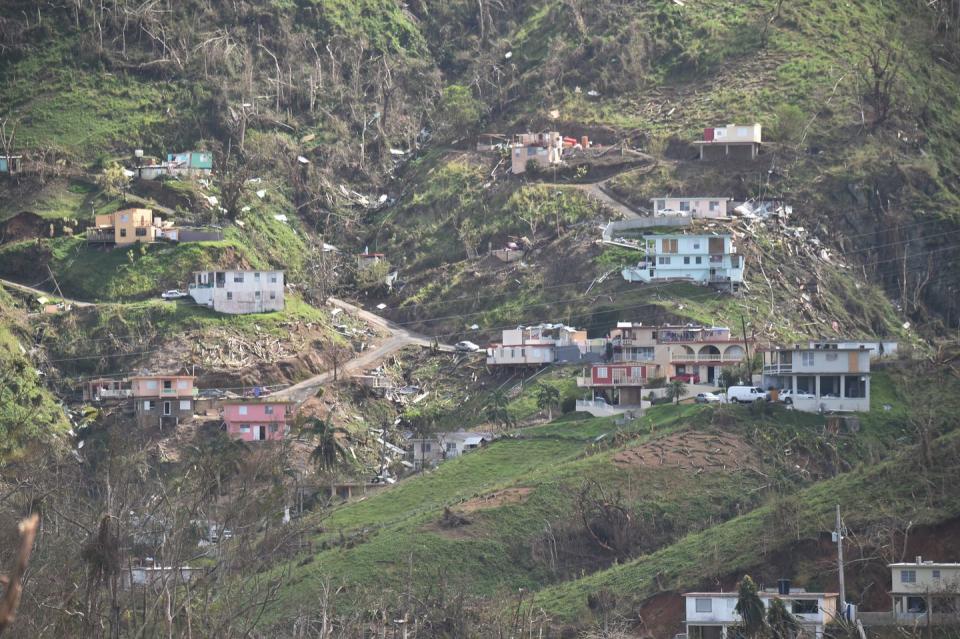

My uncle lives in the Bunker Hill section of Naranjito, Puerto Rico, a place once known for its coffee and tobacco and now home to clothing factories. Retired, he spends his days tending to his wife Luz who, after suffering multiple strokes, could barely walk.

Naranjito is located in the central region of the island, where the roads were blocked for days after the hurricane. Naranjito is not San Juan, where all eyes watched as Mayor Carmen Yulín Cruz took to the media to beg for help for her people nine days after the storm hit. If the capital of Puerto Rico was in bad shape, how were all the other families living in those hidden towns, the ones in the mountains, the ones no one can reach?

The island is no stranger to hurricanes. They are a part of life there. In the days before Hurricane Maria hit, we didn’t know the velocity of the storm. Hurricane Maria had 175 miles per hour winds attaining Category 5 strength. The winds, I would be told later, sounded like unrelenting waves tearing things apart-palm trees, storage sheds, your car.

When the hurricane landed I happened to be visiting my parents in the Bronx from Los Angeles, where I currently live. My parents, both 75 years old, watched their television screen intensely, searching for clues.

“I used to walk in that plaza. Now look at it. It doesn’t exist,” my father said, shaking his head while my mother covered her mouth. I didn’t know how to comfort them.

“Have you heard anything from your family, from Tío?” I asked. They didn’t respond.

We followed every lead. Emailed people we didn’t know. Asked everyone we knew for help. My friends offered prayers. Some asked me where they could donate money. And others online asked if Puerto Rico was part of the United States.

In Boston, I attended a teen book festival to promote my young adult novel, The Education of Margot Sanchez. A mother and her young daughter came up to me during the signing.

“You’re Puerto Rican,” she said. “So am I.” There was a slight pause and then she asked the question that would accompany me the following days and weeks after the hurricane: “How’s your family?”

There are times when a person will ask you this question only because they are following a script. They are looking to hear the words “everything is fine” and avoid uncomfortable feelings. I always wonder how we continue to show up for these sometimes hollow conversations. I am in the public and sometimes it’s not possible to pretend but I do. Maybe it was because she was Puerto Rican that I couldn’t follow the usual script. I said we didn’t know how my family was doing and I tried to keep my voice from trembling.

The first time I visited Puerto Rico, I must have been around five or six years old. My grandmother lived in Corozal, in the mountains of the island. Abuela Petra sold limbers, the Puerto Rican version of an Italian ice, and candy from her garage: dulces de coco, mampostial, dulce de anjonoli. When Abuela Petra left us alone to man the store for a second, the neighborhood kids came over asking to buy a limber. Instead of Spanish, we bombarded the kids with English. “What’s your name? What do you want? We from the Bronx.” The kids looked at us like we were space aliens from another planet.

Abuela Petra screamed at us to get away from her store. We were chasing away her customers with our English.

Puerto Rico was not our home. We were from New York, from the Bronx. Our Spanish was Spanglish. We listened to hip-hop and freestyle. We thought salsa music was our parents’ music. In Puerto Rico, we were the other.

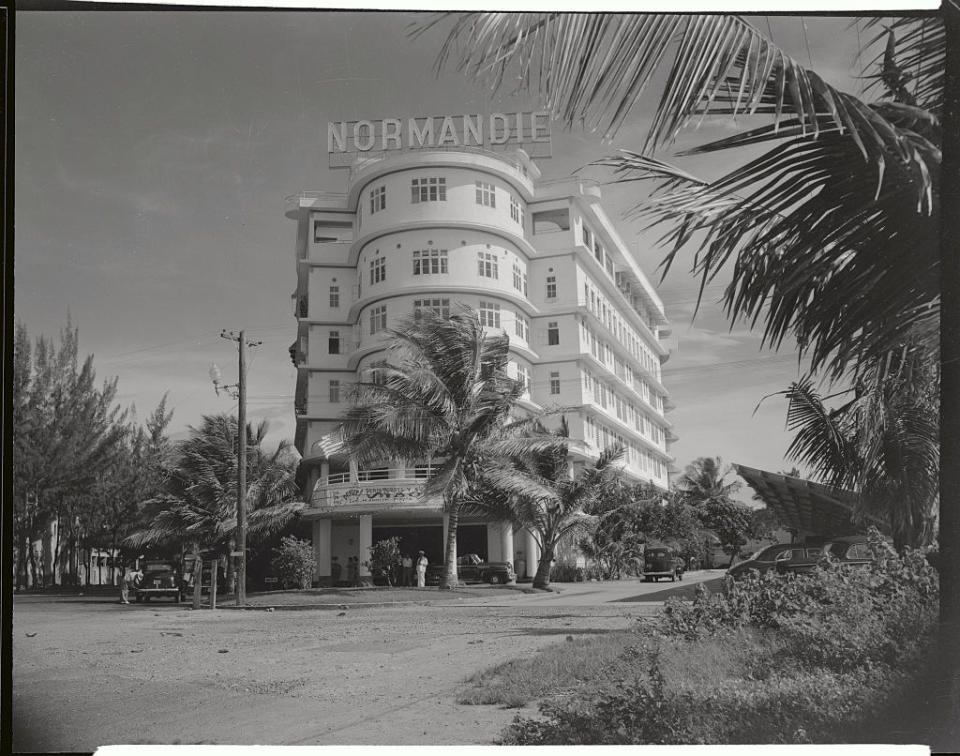

That feeling never deterred me from expressing my love for the island. Didn’t I raise my Puerto Rican flag every year at the Puerto Rican Day Parade? I even got married in El Yunque, the rainforest of Puerto Rico, to the chagrin of my family who thought surely only this Americana would force them to drive up to the rainforest. We held the reception at the Normandie Hotel in San Juan, shaped to look like the ocean liner S.S. Normandie. When we told the wedding coordinator that we wanted them to serve traditional food, she didn’t understand.

“Traditional food? We don’t really serve that here during the summer. That’s more during Christmas.”

She suggested more American fare, like Italian food. But we convinced her. This Americana wanted desperately to connect to the island, knowing full well it wasn’t truly mine. My friends flew in from New York to attend the wedding. We had a DJ play salsa and hip-hop and freestyle.

Although registered under the U.S. National Register of Historic Places, The Normandie Hotel is abandoned now, permanently closed since 2009. There is a video showing the empty hotel with graffiti tagged on the walls and the ballroom where I danced my first dance missing parts of its ceiling. I can only imagine how much worse the hotel looks after the hurricane.

As for El Yunque, the rainforest lost all its foliage and 30 to 40 percent of its trees because of Hurricane Maria. El Yunque’s wild Puerto Rican parrot population was already endangered before the cyclone hit. According to biologists, only 3 of the 56 native specimens survived.

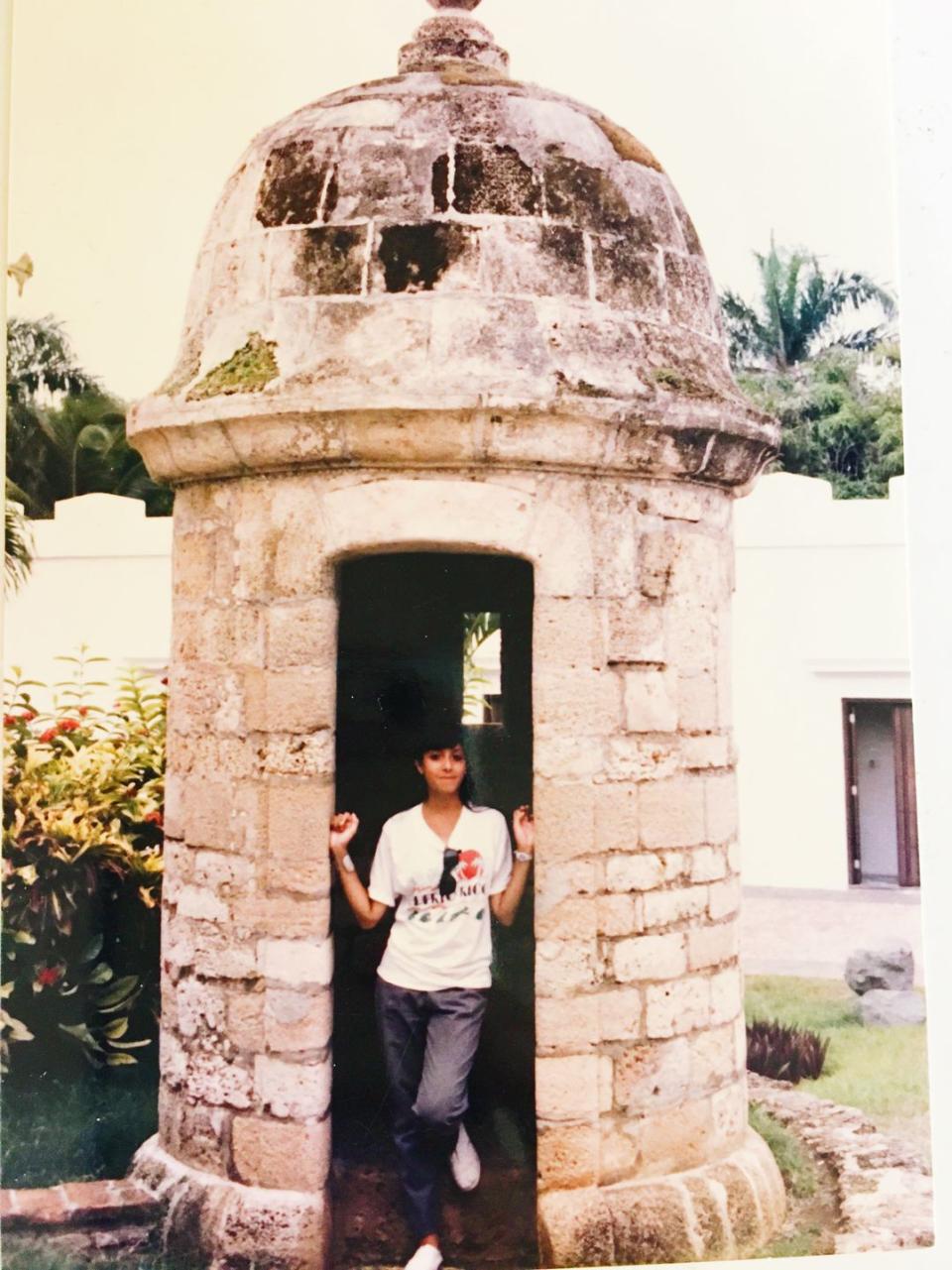

When I was fifteen, my parents sent my sister and me to Puerto Rico to spend the summer with Tío Primitivo. By then we were heavy into wearing 80’s outfits and listening to new wave music. My body was changing. I was a surly teenager who didn’t quite know how to express herself. I lined my eyes with black eyeliner like a raccoon and covered my body with Avon’s Skin So Soft to stop the mosquitos from eating me alive.

“They know you’re from New York,” Tío Primitivo teased. “You’re blood is sweet to them.” To me, it was a clear indicator of how much I didn’t belong.

My uncle didn’t know what to do with us. He wasn’t used to having girls in the house, let alone girls who expected to be taken places. He thought it was enough to have us visit. Instead, we rebelled.

We made friends with the boys next door. They were cute and tall but my uncle didn’t like that-didn’t really like them, I think. We can tell there was this unspoken rule of protecting us from making dumb mistakes.

When my uncle refused to take us to the capital, my sister and I found a way. We picked up a carro publico to take us to San Juan. We spent the whole day there, doing all the tourists things. When we returned back to the house late, my uncle was pissed.

“You can’t go off by yourself. This isn’t New York,” he said.

We looked at him like he was crazy. Who was he trying to cage up in his house? We were disrespectful. We talked back. I can still see Tío Primitivo angry at what we had become.

Tío Primitivo got on the phone with my father. We thought for sure we were going to be sent back to New York, our father siding with his older brother. Instead, my father didn’t say a thing. I think he was even a little proud his daughters figured out how to navigate that island.

Ten days after Maria hit, Tío Primitivo was finally found. It took a member of the hip hop collective Rock Steady Crew, Jansy Gonzalez, to do so. Jansy toured the island during those early weeks trying to connect with those forgotten. He documented his trip on Instagram, his truck full of bottles of water and basic essentials that he gave out. When Jansy reached my uncle that late afternoon, he posted a video of him. Back in Los Angeles, we gathered around our kitchen to watch the video on my phone. I cried because at least for now we knew. A complete stranger found my uncle with no agenda, only heart.

On October 3, 2017, the man currently seated in the White House went to survey the island after being quoted as saying the U.S. was doing an “amazing job” with recovery efforts. He then proceeded to throw paper towels at select residents of San Juan while the governor of Puerto Rico Ricardo Rosselló took selfies with him. The man stayed for four hours and left satisfied at what a great job his administration was doing. Back then the official death toll was 16. Later, reports would say aid was being held up in storage bins, rotting away.

Meanwhile, family members were without electricity and running water. We mailed generators to them and lit candles in prayer. My uncle was found but keeping him safe and healthy was an ongoing effort.

I watched this man’s disgusting display on television and thought, how much rage can one person hold?

It’s now been a year since Hurricane Maria landed on the island. This month the Milken Institute in an independent review revealed that closer to 3,000 people died in Puerto Rico in the six months that followed the natural disaster. I spend hours reading all the articles pouring in from the island. All the images taken of families still living without rooftops. Schools no longer planning to reopen.

My writing goes back to the island and my complicated relationship with it. I am who am I because my father left Puerto Rico to avoid working a hard life on a sugar plantation. My mother left because she no longer wanted to take care of her sister’s kids. So they tried their luck in the Bronx with labor work, factory work, work in kitchens. Jobs that so many never want.

My forthcoming book Dealing in Dreams is set in the fictional near future, but it hints at Puerto Rico’s real past, at the way medical experimentations are done upon the unsuspecting. It explores this idea of home, how we are all searching to carve space in a world that is hell-bent in keeping us down. And there’s anger. So much anger.

Power outages continue to plague the island. The government of Puerto Rico predicts that 200,000 more residents will leave for places such as Florida, New York, and Texas. On September 18, the man in the White House took to twitter to state that “3000 people did not die in the two hurricanes that hit Puerto Rico.” There is something quite harrowing in witnessing a plainly racist president deny American citizens not only their life but also their death.

After my uncle was found, there was talk of him moving to the Bronx. My parents actually spoke of converting the dining room into a temporary bedroom. We thought for sure he couldn’t possibly stay in Puerto Rico, not when the hurricanes were due to come back. But my uncle refused. He’s from the island. He’s not going anywhere. That was what he said anyway. In recent months, his bravado diminished. In July, Tío Primitivo got into a car accident. He is fine but his car was demolished and he can no longer drive. Tío Primitivo confessed he’s fallen into a depression. He feels alone on that island. Isolated.

This week, my aunt picked up Tío Primitivo at JFK Airport. At 80 years old, he is now tasked with finding an apartment in the Bronx for himself and his wife.

('You Might Also Like',)