In Ohio, a congressional candidate leaves a trail of court cases and controversy

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

As 11 congressional candidates prepare for Ohio's March 19 Republican primary to choose who will compete to succeed U.S. Rep. Brad Wenstrup, one hopeful has spent the past decade leaving behind a trail of lawsuits, criminal charges and controversies not just in various Ohio cities but in other states as well.

Derek Myers – a man whose ties to former New York Rep. George Santos made headlines last year – has been either a plaintiff or a defendant in multiple civil and criminal cases covering a bevy of issues and allegations.

Some of those cases have been reported on – such as a charge of illegal wiretapping leveled against Myers after one of his independent publications, the Scioto Valley Guardian, published leaked audio from the Pike County massacre trial against the judge’s orders. Myers had First Amendment allies in his corner, including the Committee to Protect Journalists, and the charges were later dismissed.

The Enquirer uncovered other cases that have not been reported before. Myers was charged with assault and disorderly conduct in Circleville. He was accused of pretending to be a police officer in Washington Court House. He was barred from attending a relative's funeral.

The matters are sometimes related to Myers’ work as a self-employed journalist. Taken in total, the incidents paint Myers as a confrontational and litigious man who sometimes has been praised for his aggressive style of journalism, though that same attribute has often landed him in contentious legal run-ins that have dragged on for years.

Several of the cases were dismissed before trial, while others that initially resulted in Myers being found guilty or held liable were reversed on appeal. In many of the cases, Myers represented himself pro se, meaning he served as his own attorney. At least three civil cases involving Myers were still pending as Primary Day nears.

It’s a complicated back story spread over multiple counties over more than a decade, resulting in little media coverage outside of brief reports about individual arrests. Up until now, much of what has been known about Myers has come from the news outlets he himself has founded.

More: Read Derek Myers' full response to Enquirer questions

'Keep your nose out of my family'

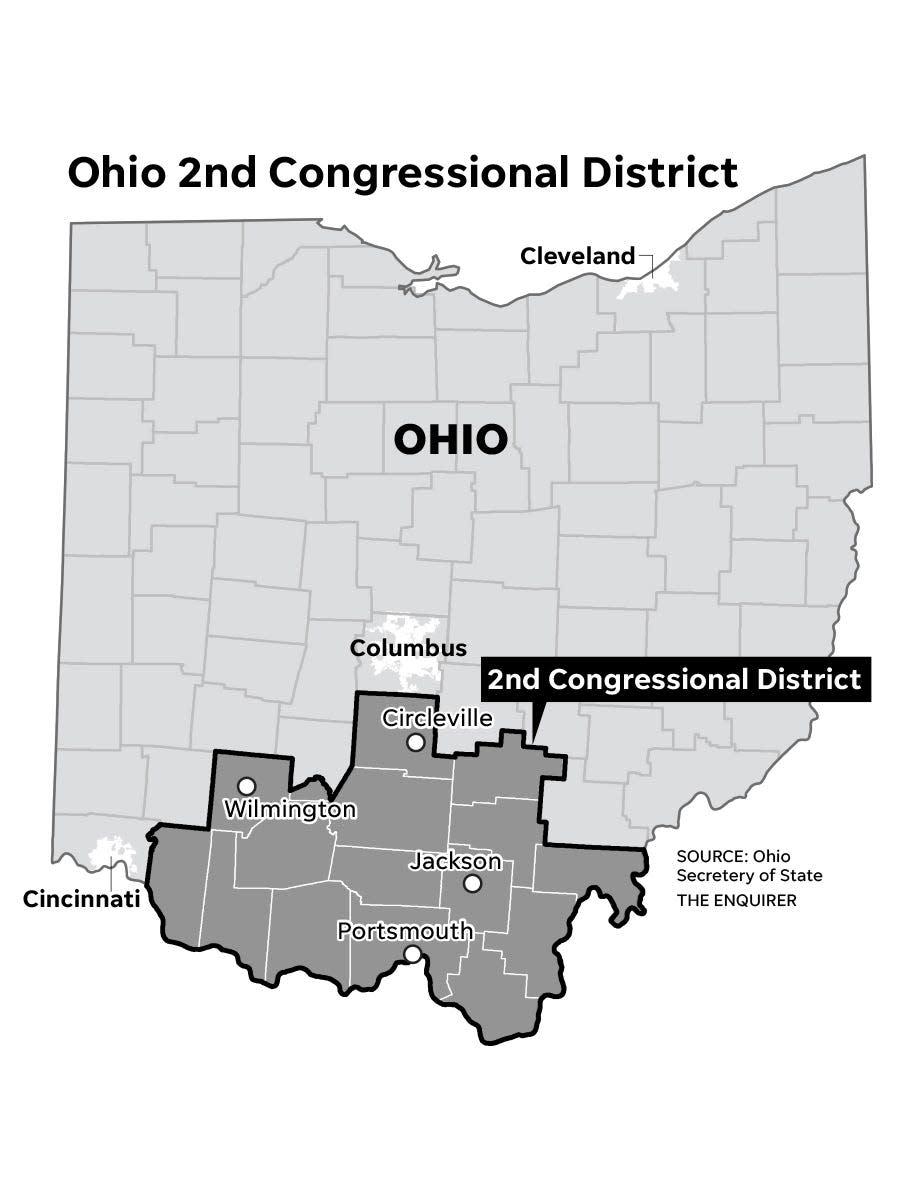

Myers, 31, has been among the pricklier candidates aiming to succeed Wenstrup. He's one of 11 Republicans vying for the open seat spread across 16 counties in southern Ohio. Wenstrup announced in November 2023 that he wouldn't seek reelection, citing a desire to spend more time with family. In response to a survey by The Enquirer, Myers refused to provide his birthdate (he submitted 00/00/0000; he was born May 8, 1992) or details about his family.

“Keep your nose out of my family,” he wrote. “That’s what’s wrong with Joe Biden and liberals like this publication: always trying to get into our homes and tell us what to do; how to raise our children. How about you don’t worry about my family?”

Myers, in an interview with The Enquirer in November 2023, said he grew up in Fayette County, raised by a grandmother who worked as a nurse in the state prison system.

When asked where he went to college, Myers said he worked on his family’s farm. He didn’t say what was grown or raised on the farm.

“My family had some farmland in Fayette County,” he said. “And so about from the age of 12 I started driving a tractor and learning how to how to take care of the farm and mow yards.”

When The Enquirer in March asked Myers about his previous legal run-ins, Myers provided a written statement saying that "each and every arrest has been 100% dismissed," which he then contradicted by spelling out a conviction of an obstruction charge that he said was leveled for "political motivations" by an officer who "was not trained enough to handle someone of Derek's caliber."

Myers' statement continued: "In the words of his mentor and great friend, Roger Stone, 'I will do anything necessary, short of breaking the law.'"

(Stone's full quote is actually: "I will do anything necessary to elect my candidate, short of breaking the law.")

Myers' self-described longtime interest in politics overlapped with another: his drive to work as a journalist. In 2010, a story in Hillsboro, Ohio's Times-Gazette identified Myers as the editor of a now-defunct Internet news site called the Washington Blaze. The story was headlined: "Area editor charged with impersonating police officer."

The then-18-year-old Myers was accused of claiming to be a police officer as he tried to glean the condition of a juvenile patient from the Fayette County Memorial Hospital. Myers vowed to fight the charges, saying he was falsely accused. It's unclear how that case was resolved.

In 2012, Myers registered a company in Fayette County called Gump Communications LLC, with the Ohio secretary of state. Myers would have been 20 at the time. Under Gump, Myers launched a publication called the Fayette Advocate, which he described in one court filing as “a hyper-local news source.”

The publication covered, among other municipalities, the village of New Holland and eventually led to a contentious relationship between Myers and multiple village officials. In legal filings, Myers accused New Holland officials – particularly then-Mayor Clair Betzko and Police Chief William “Jason” Lawless – of refusing to answer the questions he posed as a journalist. Myers also alleged that after he ran critical stories about village happenings he deemed shady, officials and some residents started harassing him.

Betzko and Lawless insisted Myers was the harasser. Lawless testified that he’d fielded complaints about Myers’ “reckless driving, as well as allegations of harassment and stalking,” according to a filing in one of the suits.

Court records suggest that 2017 was a particularly volatile year for Myers in New Holland. On Aug. 14, he was removed from a village council meeting for allegedly becoming “disruptive,” prompting council member Vivian Wood to file a complaint saying she feared for her safety, in part because “he represented he had obtained a concealed carry permit.”

Myers initially was charged with menacing and disturbing a lawful meeting, but he eventually pleaded guilty to a lesser charge of disorderly conduct.

Soon after, Myers alleged that the village’s clerk, Shannon Clegg, told him in a phone call that New Holland officials planned to threaten him if he didn’t drop a story he was working on. A federal judge, when presented with a recording of the phone call between Myers and Clegg, determined that Myers’ allegations weren’t true, writing: “This Court finds Plaintiff’s counsel’s representation of this phone call seriously troubling … Almost all these representations are false and do not accurately capture the nature of this phone call.”

The tension between Myers and New Holland officials wasn’t lost on residents.

“He’s tearing up my town,” resident Brenda Carroll told the Record Herald in late 2017.

The back-and-forth in New Holland continued for years, culminating in what Myers described in court filings as a village-sanctioned “Derek Myers Sucks Festival” in early summer of 2018. The federal court found that the village did host a festival, though not one about Myers.

The following April, Myers filed a suit against the village and several officials, accusing them of falsely arresting, threatening and harassing him in retaliation to his news stories about the municipality. He said the encounters had left him with post-traumatic stress disorder. While several of the allegations he'd leveled were undercut by the higher court, the justices did agree that it seemed village officials inappropriately retaliated against Myers with unjustified arrests.

The case was ultimately settled and dismissed with prejudice – meaning the claims can’t be refiled – in 2022.

From Lousiana to Ohio, a trail of controversy

Before the New Holland case unfolded, in 2015, Myers worked for a TV news station in Baton Rouge that fired him after a confrontation with U.S. Sen. David Vitter. After Vitter had officially qualified to run for governor, Myers approached him in a parking lot to ask questions about dalliances with sex workers the candidate had admitted to in 2007. Vitter ignored the questions and climbed inside his family’s van, where his wife was waiting.

“When’s the last time you cheated on your wife, Sen. Vitter?” Myers shouted while shoving a microphone through a cracked window of the politician's van, according to a book about the gubernatorial campaign titled "Long Shot: A Soldier, a Senator, a Serious Sin, and an Epic Louisiana Election."

Myers was fired soon after.

Several people contacted for this story who'd had publicized run-ins with Myers declined on-the-record interview requests.

Per court filings and accounts published on his own news sites, Myers was, at various times between 2016 and 2023, operating the Fayette Advocate, working for the Pike County Sheriff’s Office and operating the Scioto Valley Guardian, truncated in legal filings to simply The Guardian.

During this period, he was:

Accused of violating a protection order filed against him by a Washington Court House man. (A conviction in the case was reversed on appeal.)

Barred from attending a relative’s funeral, a move that sparked him to file a request asking the court to intervene and to reward him $25,000 in damages, requests which were denied because Myers lacked “necessary standing.”

Served a complaint alleging he’d caused a car wreck for which he was ordered to pay more than $4,000 in damages.

Accused of publishing a fake suicide letter from a 28-year-old woman who had been missing for two months before her body was found in Ross County in May 2022. The father of the woman told The Enquirer he threatened legal action against Myers.

He was also busy filing his own court documents, including:

Affidavits accusing Kendra Redd-Hernandez, a Washington Court House city council member, of conflicts of interest related to a city loan granted to a floral shop she owned. (Myers’ publication, the Scioto Valley Guardian, ran an article bylined by Myers saying that “a request for criminal charges has been filed.” The article did not mention it was Myers who had requested those charges.)

A lawsuit looking to compel Chillicothe officials to respond to his Guardian records requests.

Another lawsuit on behalf of the Fayette Advocate accusing Washington Court House City Manager Joseph Denen of defamation and slander, invasion of privacy and tortious interference.

The last suit was sprawling, accusing Denen of slandering Myers by saying he had been under criminal investigation (to which Denen’s response invoked “truth as a defense”) and also of interfering with a business deal Myers and his Gump Communications entity was trying to make with an outfit called Pennmark Management.

The details of the allegedly derailed business dealings are both convoluted and unusual for a news publication. In a court filing, Myers said that through the Fayette Advocate, he had provided advertising rates to Pennmark Management with hopes of selling displayed ads on the Advocate’s website.

The filing adds that Myers aimed to “benefit financially” from Pennmark’s planned development of an indoor sports complex: “It was proposed by Plaintiff Myers that his company – Gump Communications LLC – be hired by Pennmark as a consulting firm.”

But Myers alleged that Denen nixed that deal by warning Pennmark the city would not assist in any development that included Myers. Myers eventually dismissed the lawsuit.

Enter George Santos

Some recurring themes arise when perusing the various court filings related to Myers. He’s repeatedly been cited for speeding – one officer reported clocking him at 94 mph in a 65 mph zone – and other traffic violations. The Enquirer found dozens of traffic citations issued to Myers in multiple Ohio jurisdictions, as well as various misdemeanor non-traffic charges.

The charges – some of which were dismissed either outright or after Myers paid a fine – often appear related to his journalism work. For example, Myers was arrested on allegations of disorderly conduct in October 2023 after a Ross County Sheriff's deputy said Myers refused repeated orders to step away from an active structure fire.

Sgt. Zachary McGoye wrote in a report the burning home was "completely engulfed" and that Myers entered the active scene to take video and pictures "and posed a safety hazard by his presence." McGoye arrested Myers "when it became evident that Derek would not listen to me or comply with the lawful order I had repeated several times already."

According to McGoye, Myers berated him and repeatedly said: "I'm going to argue with you. You can take me to jail. This is the worst mistake of your career. Think about what you are doing." In his report, McGoye wrote, "I don't recall how many times Derek kept repeating these statements over and over again."

The charges against Myers are often dismissed, but not always. Court records indicate he was found guilty of obstructing official business and recklessly operating a vehicle in January 2018; of disorderly conduct in April 2018; and of a restraining order violation in November 2018.

While those cases are several years old, other entanglements are much fresher. Myers has an ongoing, public feud with former New York Rep. George Santos, who’d gained notoriety after his 2022 election when it came to light he had fabricated much of his biography during his campaign.

Myers was briefly courted for a job in Santos’ office, though the position never materialized. Santos has said he lost interest in Myers after learning about the wiretapping charges stemming from the Pike County massacre trial. Myers alleged that Santos sexually harassed him.

The two continue to spar on X, the social media site formerly known as Twitter, with Santos recently calling Myers a “poster child for insanity” and a “vile human,” after Myers claimed Santos was “throwing a hissy fit because I’m on my way into Congress while he was pushed out.”

Closer to his Chillicothe home, Myers has been mired in controversy both as a candidate and in connection with his Scioto Valley Guardian publication.

A.J. Good, a Chillicothe resident who has been outspoken about Myers, said Myers has become a reviled figure in town – and that has had its benefits.

"I really felt a sense of unity in Chillicothe," Good said. "That unity continues every time I see a video of him publicly speaking, with a comment section full of jokes at his expense. It’s a beautiful thing. Derek Myers, Chillicothe’s walking, talking meme."

That divisiveness has come courtesy of stories Myers ran on his Guardian site, such as one headlined “Chillicothe’s Mayor Used Cocaine While in Office, Says Man,” which quoted an unnamed man described as “a drug dealer serving decades behind bars.” The story ran days before Election Day in November 2023; Mayor Luke Feeney won reelection.

When reached by The Enquirer, Feeney didn't want to comment on the record, saying he hasn't responded to the stories Myers has written.

The Guardian also published a series of articles claiming that Adena Regional Medical System provided improper medical care.

The Guardian ran stories claiming, among other things, that former physician Jarrod Betz had propped a dead woman up to appear alive to her family members. Despite the news site saying the patient’s family had filed a lawsuit in the case, The Enquirer could not find such a suit nor confirm details of the case.

Documents suggest, however, that Myers offered Adena a respite to the negative news coverage. In a flyer obtained by The Enquirer, The Guardian offered Adena advertising rates that, at the highest tier, offered "editorial discretion" for $12,500. Asked by Adena officials what that meant, Myers wrote that Adena would have the power to nix stories it didn't want published.

Such an arrangement – offering a business the ability to nix news stories about itself in exchange for money – violates journalistic ethics, said Chris Roberts, vice chair of the Society of Professional Journalists Ethics Committee and associate professor of journalism at the University of Alabama.

"The reason for journalism is to tell people things they don’t know," Roberts said. "It’s not to sell work to the highest bidder or be paid off so you don’t tell the public what you know."

'I think he had good intentions'

Myers' behavior over the years has baffled many.

"When he first started (The Guardian), I think he had good intentions," said Gunner Barnes, who ran for Chillicothe City Council this past November and has been a target of some of Myers' reporting. "I think the money got to him, and then he started weirdly going against the community that he was trying at first to help."

Some of the critical information published by Myers’ site about Adena coincided with claims posted to a Facebook page “Blimp Arms." The administrator of that page identified himself in October as "Derek" in a message to an Enquirer reporter that was quickly deleted. The previous month, Myers had filed a lawsuit against two plaintiffs listed as John Does #1 and #2 that accused the unnamed people of running a separate Facebook page called “Blimp Arms Exposed” that, he alleged, accused him of not just of being “Blimp Arms” but also of having a history of legal run-ins.

That case is still pending. One of the more recent filings in it is an affidavit of indigency, in which Myers reported he earns no money through employment, earns none through unemployment and has no cash on hand.

Among other pending matters is a lawsuit by Betz, the former Adena physician, as well as another suit Myers filed in December against Pike County, its sheriff, a deputy and a police captain. That suit alleges that Myers' rights were violated when his cell phone and rented laptop were seized amid the wiretapping case in 2022.

While Myers has said he's stepped down from the Scioto Valley Guardian because of his congressional campaign, the publication still runs articles without a byline.

In the meantime, Myers has brought his confrontational personality to the campaign trail. He called one of his primary opponents "a foreigner." When a TV station labeled the attack as racist, Myers threatened "legal action."

Could Myers upset the field of 11 candidates and win? Several GOP officials have told The Enquirer that seems unlikely.

Myers met with the Scioto County Republican Party recently. Exactly what happened or what was said, county party vice president Kevin Craft didn't want to say.

"He certainly didn't make any friends at our committee meeting," Craft said.

This story has been updated to specify which court heard Myers' claim, and to reflect that Myers is no longer under investigation for a structure fire.

Chillicothe Gazette reporter Shelby Reeves contributed to this report.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: Who is Ohio GOP congressional candidate Derek Myers?