Oak Ridge grad shares about his late wife's deafness, reasons behind his love of Beethoven

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Benita Albert concludes this two-part series on Robin Wallace. Notice her innovative use of technology while she writes about Robin’s life. She “asked Alexa” to play certain music while she was writing Robin’s commentary and analysis of that same music. Isn’t technology just grand?

Enjoy the rest of Robin’s life story.

***

Robin E. Wallace is a recognized Beethoven scholar, a professor of musicology at Baylor University, and a 1973 graduate of Oak Ridge High School. After he received a Ph.D. from the Yale University School of Music in 1984, his professional journey has included teaching assignments in various university programs across the United States, a postdoctoral fellowship, a two-year stint as a high school English teacher and guidance counselor, and a private piano instructor.

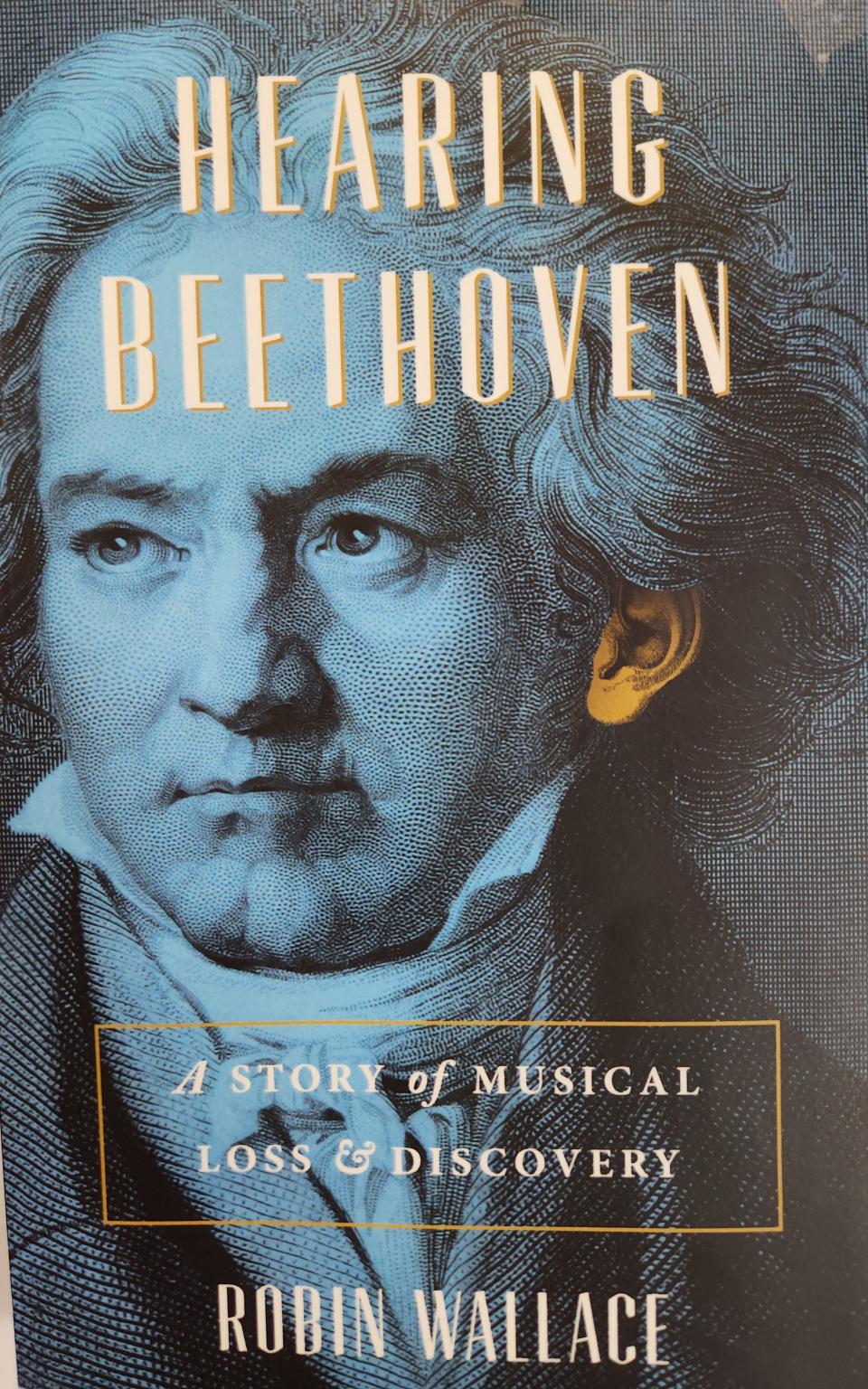

During the past three decades, Robin has served as an associate professor of music history at Converse College (1994-2003), followed by his current assignment as a professor of musicology at Baylor University. During his Baylor tenure, Robin has published two noteworthy (no pun intended) books: “Take Note: An Introduction to Music Through Listening” (Oxford University Press, 2014) and “Hearing Beethoven: A Story of Musical Loss and Discovery” (University of Chicago Press, 2018).

Robin’s infatuation with the works of Ludwig van Beethoven began early on, greatly influenced by his experience at a music arts camp during his high school summers. I asked him to describe Beethoven’s music and what it was that spoke so deeply to his young self. He shared the following words from the personal memoir he is writing.

“What is it about his (Beethoven’s) music? He has been the most popular classical composer for at least a couple of centuries. His name attracts superlatives: The Behemoth of Bonn, The Man Who Freed Music, The Greatest Composer Who Ever Lived. He is often held to be the first musician whose cultural influence can be compared to that of Shakespeare or Michelangelo. His scowling bust appears on billboards and TV commercials.

“And then there is his deafness. By the commonly told version of the story, Beethoven figures out he is going deaf in his thirties, and by the time he writes his fifth symphony (Fate Knocks at the Door) he is virtually unable to hear his own music. Nevertheless, he goes on composing for two more decades, becoming an Inspirational Cultural Hero. His story is the most heart-wrenching of all the tragic stories of great composers’ lives; while he didn’t die in his thirties like Mozart and Schubert, he went through a kind of death at the same age, and unlike them, he had to go on living afterward and struggle with the results.

“All of this would be only so much hype if his music didn’t speak to me of profound and eternal truths. But it does. After listening to one of the late quartets, or to the last piano sonata, Op. 111, I experience a kind of ecstasy I cannot hope to describe. I simply know that these pieces of music are the greatest things people have ever created. In the brave new world they reveal to me, life has more meaning and potential than I had dared hope; mankind is a beautiful and noble race to which I feel proud to belong.”

Commenting further on his young mindset, Robin added, “This is heady knowledge for a fifteen-year-old. Whether I understand it at the time or not, it means my life is spoken for. I have my calling. I will spend my life sharing this treasure with others.”

He continued, “As Felix Mendelssohn famously said, ‘Music is more clear than language, not less so. What it has to say is primal; it exists at the very source of human consciousness, and all meaning radiates from that source.’ Of course, I can’t put that into words at fifteen. I intuit it, though, and I begin my quest for the Holy Grail that is the meaning of music. Beethoven will be my guide.”

Robin’s professional and personal journey could not be more dramatic in an uncanny intersection of fates, the midlife onset of deafness in both his late wife Barbara, as well as his revered Beethoven. Both struggled with hearing loss and became profoundly deaf in their last decade of life.

Barbara and Robin married in 1989, in their early 30s. They joyously welcomed the addition of two children soon after. They were excited to see Robin’s career dreams advance with a move to Baylor University in 2003. Barbara had required radiation treatments for a brain tumor in her 20s, the radiation administered through her ears. Resultant, progressive hearing loss eventually led her to employ hearing aids, but by 2000 all hearing in her right ear was lost. Only three years later, as they were packing for their move to Baylor, Barbara suddenly and unexpectedly lost all hearing in her left ear.

In the Introductory Chapter of “Hearing Beethoven,” Robin recalled the moment when Barbara screamed, “I can’t hear anything.” He wrote, “Spoken words were futile. So, I did what, as a Beethoven scholar, I knew Beethoven and his companions had done during the final decade of his life; I picked up a legal pad and began a ‘conversation book’ in which I could write to her while she responded orally. We would fill dozens of them over the next several months.”

Robin continued, “I now met deafness face to face. I had always known that Beethoven struggled with the most devastating handicap a musician could ever encounter. I also knew that he experienced profound social isolation during the last part of his life. I was intimately familiar with Beethoven’s music, and I thought I understood his suffering. … But I had never spent significant time with someone who was profoundly deaf. That was about to change and so was the trajectory of my life.”

Barbara described her deafness as “social isolation.” She had to give up her nursing career, and she experienced deep frustration in attempting to participate in events such as family dinner conversations and in hearing church music and liturgy, which Robin said was an anchor in her life. His recounting of her next eight-and-a-half-year struggle to hear again via auditory technology aids and her resoluteness to maintain a semblance of normal life are sensitively told by Robin.

The book interweaves personal narrative with scholarly musical research to create a fascinating treatise on the indomitable human spirit. From Beethoven’s accommodations with ear trumpets and piano modifications to Barbara’s pocket talker and later cochlear implants, both strove to retain their social and professional freedom. Robin has written a deeply humane study of adaptation and courage, an introduction to the sciences of neurology and audiology, a musical discourse on the compositional and performative process, and a love story to his late wife.

Not having a background in music, I found myself compelled to “ask Alexa” to play book-cited pieces such as Piano Sonata in F Major, op.10, no. 2 (composed in 1796) so that I could enjoy the music while also following Robin’s analysis of same. In this creative work, Robin states, “Beethoven showed an intuitive knowledge of facts about hearing that have since received scientific support.” He also observed, “If Beethoven was composing with his eyes at age 25, it is only logical to assume that he drew on this ability more and more as his hearing grew worse.”

After a period of grieving the loss of his beloved Barbara in 2011, Robin began to write “Hearing Beethoven” in 2014. His writing efforts were uplifted by the support of his new wife, Meg, whom he married in the same year. Meg was a freelance editor and indexer who, as Robin soon learned, was an exceptional book crafter and insightful adviser and encourager.

I asked Robin how his book has been received by contemporaries in the music world and by the deaf community. He answered, “Thinking of hearing, my book of course focuses on that aspect of music as well, although in a very different way. It has been extremely well received, both in my field and outside of it. For example, I was invited to give a presentation based on it to the Association of Adult Musicians with Hearing Loss, which also gave me a very positive review in their newsletter. I have been invited to present at venues like 92Y in New York and have been featured in several podcasts.” (I would recommend to interested readers the following online interview: https://newbooksnetwork.com/robin-wallace-hearing-beethoven-a-story-of-musical-loss-and-discovery-uchicago-press-2018/)

“My goal in writing the book was to write something that would speak to both the scholars and the public, and generally, it looks like I succeeded although some of the latter have found the (entirely necessary) technical discussions in the last few chapters to be tough going.”

In an extended faculty role, Robin has taught courses in Baylor’s Interdisciplinary Core, an alternative curriculum run by the Honors College. He described teaching a World Cultures III course covering Europe from 1600 to the present where he gave large group lectures on music and small group discussions on philosophers, literature, and history. At least eight faculty members from across different departments were involved.

Robin said, “All of us had to stretch to teach that course, but it was very rewarding for precisely that reason.”

Robin continues to teach, write, and publish. Meg has completed a master’s degree in social work at Baylor, and she has led the development of a non-profit disability justice coalition called Mobilize Waco. Their mission is to work toward full participation and leadership of persons with disabilities in the Waco area. Robin speaks proudly of Meg’s vision and advocacy, and he is fully sensitive to and supportive of the mission.

Robin enjoys traveling. He has visited all 50 American states, as well as five Canadian provinces. He has also traveled throughout Europe and hopes to make an extended return trip after retirement. A previous European trip gave him a rare hands-on research experience pertaining to some of Beethoven’s adaptations to hearing loss.

He visited the Beethoven-Haus in Bonn, Germany, to view and test replicas of ear trumpets Beethoven used. He also visited Ruiselede, Belgium, and the instruments workshop of noted craftsman and restorer Chris Maene, where he saw replicas of resonators (sound capturing enclosures replacing a piano lid that, purportedly, were used by Beethoven). Robin played Beethoven passages and marveled at the effects of a resonator.

“It produced a full sound with little distortion - much louder than that of the instrument itself, but not uncomfortable for someone used to playing a modern grand.” (“Hearing Beethoven,” p. 144)

Robin and Meg’s blended family counts four adult children and one new granddaughter. Robin enjoys traveling, cooking, photography, reading, playing the piano, and spoiling his grandchild. He has been writing a personal memoir from which he shared a bit for this story. Writing it mainly for his family, he said the memoir is an ongoing writing project that will extend into his retirement years.

I am deeply honored that Robin has permitted me to share his story with the Oak Ridge community, his childhood home. As his former math teacher, and specifically, as someone with no credible musical background or talent, it was necessary for Robin to become my teacher. I relish the opportunity to explore different fields of study, to enlist former students as mentors, and to feel great pride for the uniquely creative ways they are advancing knowledge and distinguishing themselves. Reading Robin’s book, listening to his articulate and passionate explanations, and valuing his scholarly observations has piqued my desire to learn more.

I confess to researching beyond our interview, wondering in what unknown-to-me ways I might have already encountered Beethoven’s genius. Online searches quickly revealed that I have heard him in personal favorites of mine from pop music. Beethoven’s “Pathetique Sonata” is used in the chorus of “This Night,” by Billy Joel. And the Beatles song, “Because,” is based on a chord from “Moonlight Sonata” played backwards. This is only the beginning of a long list of “artistic borrowers” from Beethoven’s music that I found. I will forever ‘hear music’ differently.

One of my 2024 New Year resolutions is to listen to more of Beethoven’s music starting with Robin’s annotated selections in “Hearing Beethoven.” Oh, how I would love to be a student in one of his introductory music courses for non-music majors! Thanks to Robin, I will be evermore grateful for the gift of hearing, as well as more aware of, and intentionally thoughtful for, those who are hearing challenged.

***

Thank you again, Benita. You continue to bring to life for us in Oak Ridge those who have attended school here and gone on to the great things. I look forward to your book!

City Historian D. Ray Smith's "Historically Speaking" column is published weekly in The Oak Ridger.

This article originally appeared on Oakridger: Oak Ridge grad shares about wife's deafness, why he admires Beethoven